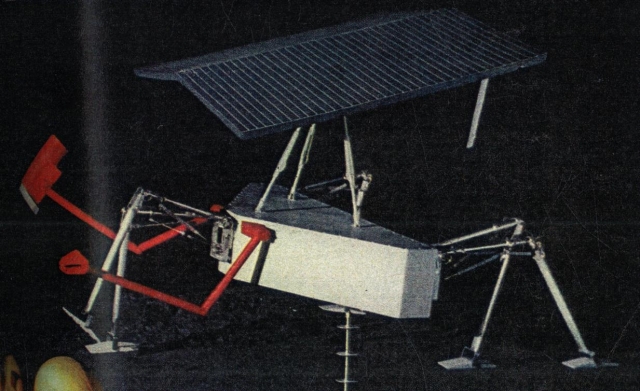

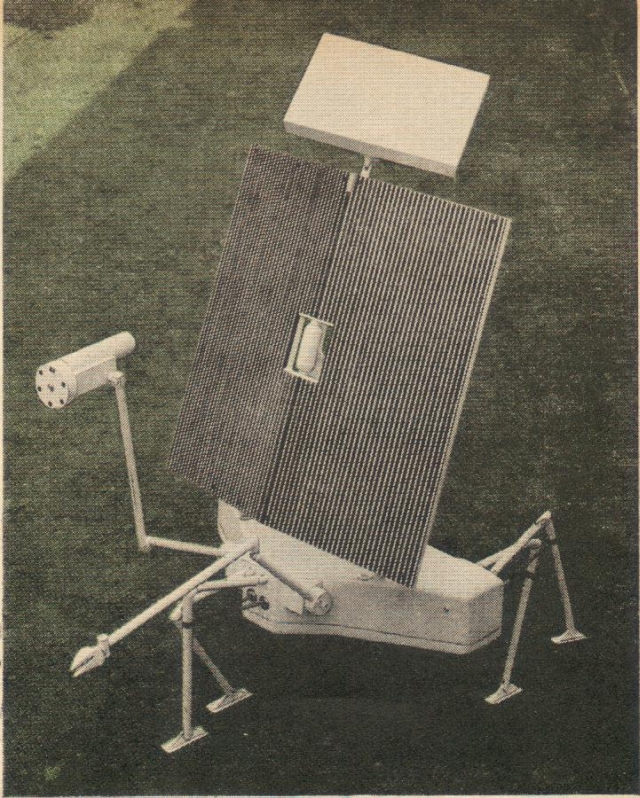

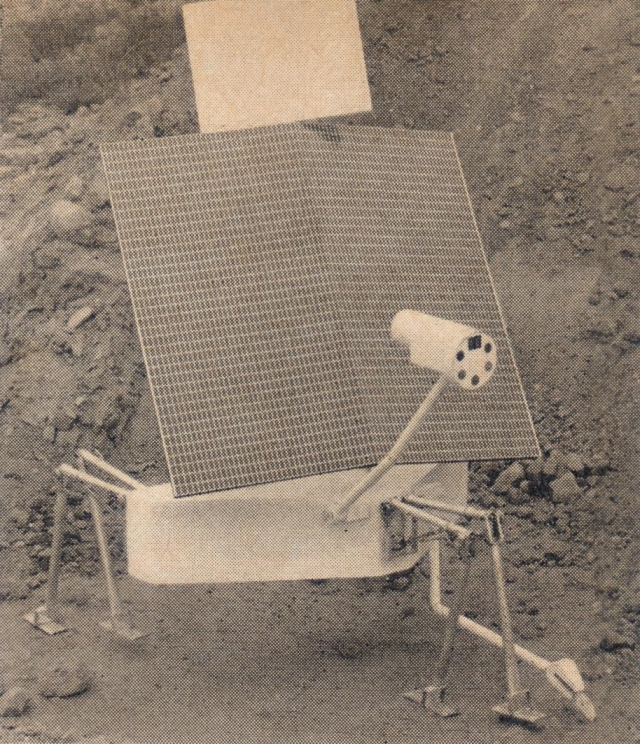

Space General designers have built an insect-like vehicle with six legs, two arms, a triangular body, a solar-cell panel, and an antenna. The left arm, ending in a claw, picks up objects to examine. The right one holds a TV camera to do the looking – and to see where the vehicle is walking. This lightweight 135-pound rover will fold to a compact 40-by-40-by-12-inch size for rocketing to the moon, where it's expected to operate for at least two months.

**video clip via youtube**

From Brodsky's book "On the Cutting Edge"

IN THE EARLY ‘60S, AS PART OF THE PREPARATIONS FOR THE APOLLO MANNED MOON LANDING MISSION, THE JET PROPULSION LAB PLANNED A FOLLOW-ON PROGRAM TO ITS VERY SUCCESSFUL ‘HARD’ LANDING ‘RANGER’ PROGRAM, WHICH GAVE THE FIRST CLOSE-UP VIEWS OF THE MOON’S SURFACE. THE PROPOSED ‘SOFT’ LANDER PROGRAM WAS CALLED ‘SURVEYOR’. AN INITIAL CONCEPT WAS FOR IT TO DISGORGE A MOON SURFACE-TRAVERSING VEHICLE TO CONDUCT A NEIGHBORHOOD SURVEY NEAR ITS LANDING POSITION. IT WAS TO BE COMMANDED BY A TV – RADIO CONTROL GUIDANCE LINK. THIS LINK WAS TO BE RELAYED TO AND FROM THE MOON VIA THE SURVEYOR’S EARTH COMMUNICATION SYSTEM. A LUNAR ROVER COMPETITION WAS OPENED AND THE RELATIVELY NEW STAR ON THE HORIZON, SPACE-GENERAL, DECIDED TO RESPOND.

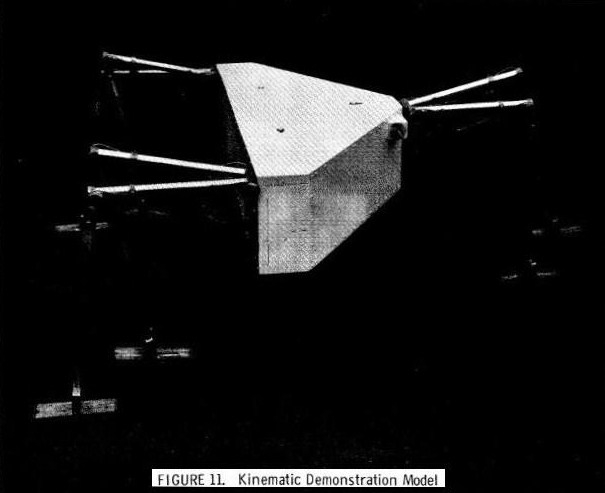

“The damned thing looks like a cross between a crazy Bull Terrier and a Peacock!”, my Boss said. After weeks of in-plant secrecy, we had finally unveiled our robotic entry in the moon rover sweepstakes. To everyone’s amazement and delight, Jack Miller was directing its peregrinations around the back forty of our El Monte campus, using a hand-held radio control link device. With its ridiculous TV camera “head” wagging from side to side on its long tubular swiveling “neck” scanning the local scenery, the six legged beast really did look outré – like a malformed hound out of Star Wars.

IN THE EARLY ‘60S, AS PART OF THE PREPARATIONS FOR THE APOLLO MANNED MOON LANDING MISSION, THE JET PROPULSION LAB PLANNED A FOLLOW-ON PROGRAM TO ITS VERY SUCCESSFUL ‘HARD’ LANDING ‘RANGER’ PROGRAM, WHICH GAVE THE FIRST CLOSE-UP VIEWS OF THE MOON’S SURFACE. THE PROPOSED ‘SOFT’ LANDER PROGRAM WAS CALLED ‘SURVEYOR’. AN INITIAL CONCEPT WAS FOR IT TO DISGORGE A MOON SURFACE-TRAVERSING VEHICLE TO CONDUCT A NEIGHBORHOOD SURVEY NEAR ITS LANDING POSITION. IT WAS TO BE COMMANDED BY A TV – RADIO CONTROL GUIDANCE LINK. THIS LINK WAS TO BE RELAYED TO AND FROM THE MOON VIA THE SURVEYOR’S EARTH COMMUNICATION SYSTEM. A LUNAR ROVER COMPETITION WAS OPENED AND THE RELATIVELY NEW STAR ON THE HORIZON, SPACE-GENERAL, DECIDED TO RESPOND.

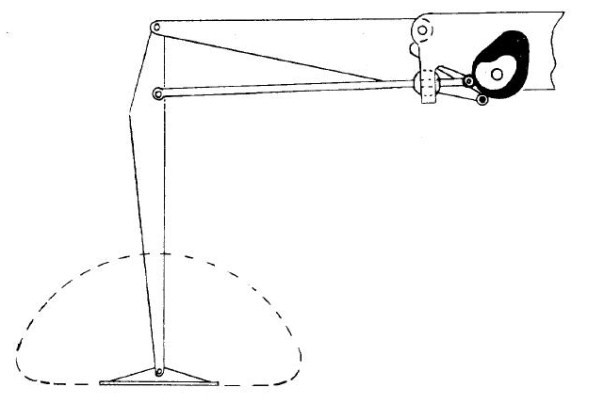

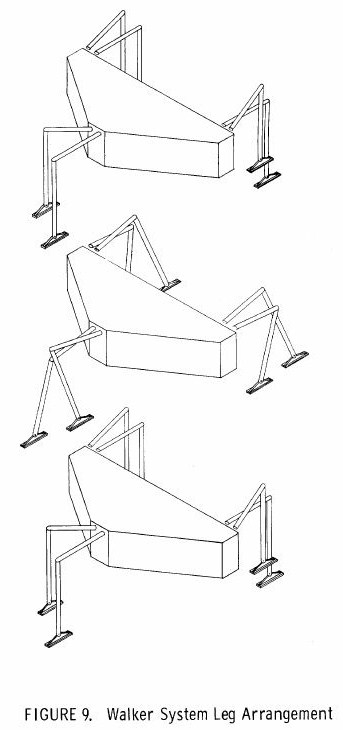

At that time, I was Chief Engineer, reporting to Dr. Fred Eimer, recently recruited from JPL by Jack Froehlich and who, in turn, had reached back there to recruit Jack Miller and Al Morrison for my Design Group. They quickly had proven themselves to be two absolutely top-notch designers. I organized a proposal team, with the sterling duo in the conceptual design lead. The design we came up with was a walking, rather than a rolling or hopping, vehicle. We believed a walker stood a better chance of navigating an unknown surface than the other options. Its body was triangular in shape, longer in the forward moving direction than wide, and about 6 inches thick. Its flat sides were parallel to the ground, with the underside standing about a foot off the ground. The swivel – mounted TV camera that looked like a Cyclops was mounted on the forward – moving point of the triangle. The aft sets of legs emanated from the other two points of the triangle, thus

96

providing a broad stable base to preclude tipping. More than covering the creature’s upper back was a square solar array which provided drive motor, communications, and TV camera power. This array was hinged near the base of the TV camera supporting “neck”, and could be raised up to a 45 degree angle to track the sun as it moved through its lunar day. At its larger angle extensions, it gave the beast the appearance of a peacock in heat! The antenna that communicated with the Surveyor was attached to the top end of the array. Adding to the fowl appearance was a forward thrusting claw at the end of a second tubular bendable “neck”, meant to pick up lunar samples, but actually looking more like a peacock pecking at the ground.

ORIGINAL “MOONWALKER” WITH STEREO

TV ‘HEAD’ AND SOIL SAMPLER CLAW

However, the feature that made it all work was the unique arrangement and motion of the three pairs of biped-like tubular legs, with both knee and hip joints, which gave it the ability to navigate through minor pitfalls such as rocks and potholes. Any larger impediments would be avoided via command from the earth operator who would see them in time to transmit a “halt” signal. The motion of each leg set looked like a dog’s front legs digging a hole in the ground.

97

The two sets of rear legs were attached to the “haunches” of the triangular body, while the single forward set was attached under the long-necked TV “head”. The footpads themselves were slightly rounded and serrated on the bottom to provide a good grip, and thus precluded the need for an ankle joint.

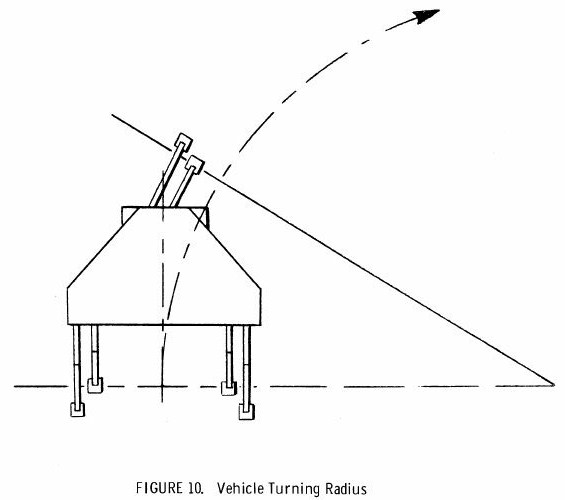

The driving mechanisms that Jack and Al devised were such that there were always three of the six feet on the ground simultaneously, moving backwards to provide forward motion. The other three leg sets, each located right next to and parallel to the foot already on the ground, were making a rapid return cycle so that they would contact the ground forward just as the propelling feet reached the end of their backward travel. Steering was achieved by simultaneously speeding up one haunch set of legs while proportionately slowing down the other side. The forward pair of legs maintained the normal pace. If forward motion was impeded before the earth controllers could act soon enough to stop and regroup, the robot automatically ceased forward travel and waited for a command, perhaps to back up and make a turn before proceeding forward again. We decided to make a full scale demonstration model of the concept as part of our proposal submittal. It stood about four feet tall from the ball of its foot to the top of its deployed antenna. It was this model that delighted our peers, with its fey look of a defanged futuristic pet. It truly was sensational!

Alas, by the end of the competition, the SURVEYOR’s final design weight had grown so heavy that the intended launch vehicle did not have the lifting power to accomplish the mission. Weight had to be dropped and, to our everlasting grief, the moon rover portion of the program was summarily deleted. When I heard the news, I almost cried. We had poured so much heart and soul in the frenzied period of the proposal effort. All the participants were simply unwilling to let go of what we perceived as a wondrous device and sought ways to revive the program. The beast was kept around the office like a pet.

R. F. Brodsky

Time Oct 20 1961 – Space-General Walker

Free Enterprise v. the Moon

Outside New York's Coliseum last week stood a Redstone rocket, white and spare, and tipped with a Mercury capsule exactly like the one that carried Commander Alan Shepard on his suborbital flight. Inside the building glittered the American Rocket Society's "Space Flight Report to the Nation"—an astonishing exhibition of the phony and the competent, the trivial and the magnificent. Some of the objects on exhibit were miracles of deft design and precision workmanship. Others were not working so well. (A computer kept typing petulantly: "I can't see a thing without my glasses.") Still others would probably never work at all. Mused an engineer about a crude device for exploring the moon: "It's wonderful what a kid can do with an Erector set."

Founded in 1930 by twelve enthusiasts, the American Rocket Society never had more than 400 members before the end of World War II. Its meetings had few if any commercial exhibitors. After the war. the society grew faster. Then, in 1957, the year of Sputnik I, it soared like one of its better rockets. By last week, ARS had 19,500 members, and most of the nation's largest corporations (including Bell Telephone, General Motors, and Standard Oil of New Jersey) were expensively represented at its convention. California air plane manufacturers moved on New York en masse, adding traditional West Coast fluff and West Coast flash—including polished feminine models to pose beside polishedmodels of space components.

Imaginative Attack. The technical papers testified to an eagerness to try anything, however difficult or bizarre, that might move the U.S. toward space. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration showed models of satellites already in orbit or soon to soar aloft—beautiful machines with the strange, angular, functional grace of well-designed space craft. North American Aviation, Inc. showed a full-scale model of its giant F-1 rocket engine, which spits out more than 1,500,000 lbs. of thrust and whose tail cone is as large as an Eskimo igloo.

Not all of the jointed robots for exploring the moon (see cuts) were outlandish contraptions; some of them were serious and imaginative attacks on the difficult problem of studying the lunar surface before humans learn how to survive there. RCA showed a six-legged[sic – Rh 2010 actually four] job that walks cautiously on circular rubber feet, a small six-legger that looks like a metal praying mantis, an inflated plastic ball, and a moon rover that creeps like a centipede. Perhaps the best thought out of the tribe was an insectlike machine made by Space-General Corp. Powered by solar batteries, it walks on long, jointed metal legs. By means of a TV camerabit transmits pictures of the lunar landscape to its masters on faraway Earth. Safe at home, scientists can tell the creature where to go, and they can also order it to pick up lunar samples with its jointed, lobsterlike claw.

When it was determined that the Atlas rockets could not lift the Surveyer with an added payload of a Lunar Rover, the project was dis-continued.

However, the Space General team involved saw a future life in their design, as a disability chair. Three were built – see here.

The design was later developed into the "Iron Mule Train" – see here.

The ideas were re-considered a fourth time by D. J. Todd in 1990 – see here.

.jpg)