Trefor Prest creates some of the most amazing and fantastic sculpture I've ever come across. I've been to Gruyeres and seen H.R. Giger's work, seen Hans Bellmer's "Machine-Gunneress in A State of Grace", and to see Trefor's sculptures is something else again. His maritime series has a Vernian feel about them, a world of Nautilus submarine melded with its underwater life after Nemo's tumultuous end, with a everlasting ability to communicate with you with the turn of a lever, wave of a wing, the opening of a hatch, all for the need of you to give it life from its suspended state.

Source: Weekly Times, July 30, 2010.

Visit Trefor Prest's studio

by Genevieve BarlowSHOULD you ever need to snatch a vision of how a mid-20th century steel pressing mill might have looked, visit Trefor Prest's studio. There at the rear of 12ha of bush at Strangways, between Newstead and Hepburn Springs, 500 metres from the house he and his teacher wife, Belinda, built, you'll find such a vision. There's a fly press that can shape brass, a Macsan flat bed lathe and lathes that huff and crank in a way 21st century machines never would. They're all obsolete, but in the hands of Trefor are all taken apart and transformed into quirky art sculptures.

"It's not as if you have to throw it away because you can't get the software for it," Trefor, 65, says. "You can see how it all works."

Point taken.The mechanics of the machines are clearly on show. There's nothing hidden from view, no hidden wires delivering messages deep inside as we have with today's computers. Just shafts turning cranks and pushing levers and so on. It's the visibility of these mechanics that holds a clue to the beautiful but bizarre works that Trefor creates.

His sculptures are made of brass, steel and other metals sometimes completed with canvas. Shapes allude to human bodies. Ribs of steel adorn round shapes that open with the push of a lever to reveal intricate mechanisms.

"Traditional sculptures are all surface but I like to emphasise what's inside," the father of three says.

Intricacy and detail are vital to his works. Recently he rescued a vast steam boiler, made for distilling eucalyptus leaves, from the bush and installed the end plate on the wall of his studio. He explains how each of the rivets would have been made with brute force. Seeing it there, one is prompted to think about the nature of work then and now. But mostly his works are compelling puzzles, enigmatic pieces that prompt the viewer to ask "what does that bit do?"

The Welsh-born son of migrants, Trefor studied at England's Croydon College of Art before he was expelled, came to Australia and became an army conscript. He later enrolled at the then Gallery School, which became the Victorian College of the Arts. He loved working with metal and completed a three-year welding apprenticeship before working with a mechanic making truck trays, among other things.

Recently, some of his works were shown during the Lake Bolac Eel Festival, but he can go years without an exhibition.

At 65, he is disappointed his works are not more in demand, yet he loves to make them and does it with as much joy and enthusiasm as he did in his 20s.

"A lot of people don't make things until they know they have an exhibition coming up and then they go into a frenzy saying 'oh my god I have to make something' but there's no joy in that. "Everything then becomes a hassle.

"I don't do things for exhibitions. I exhibit whatever I already have." Nor does Trefor design things first. Instead he begins and sees what takes shape."I used to work in a way where you didn't think about aesthetics, you just had to work out how something could work," he says.

"One of my larger pieces took three years to make. "That's when I thought 'this is ridiculous'."

A lifetime of work is building up in his studio.

It's worth a look, before fame strikes.•Trefor Prest, 134 Hepburn-Newstead Rd, Strangways, ph: (03) 54762406. [+61354762406]

Source: Australian Country Style December 1997

INSPIRED BY TALES OF THE SEA AND OUTER SPACE AND ACCOMPANIED BY THE SOUNDS OF OPERA MUSIC, TREFOR PREST WELDS AND MELDS SCRAP METAL INTO SCULPTURE.

BY KERRY ANDERSON.

PHOTOGRAPHY BY NEIL LORIMER

Fourteen years ago contemporary sculptor Trefor Prest packed his bag, loaded his family into the Land Rover and, with Doreen the donkey on the back, left Kalorama in the Dandenong Ranges to commence a new life of rural bliss near Newstead in central Victoria.

"We must have looked very conspicuous driving through Melbourne," says Belinda, Trefor's wife. 'We had Doreen crammed in the back with all the luggage."

Doreen was the main reason why the Prest family chose to move to central Victoria. Having a large block of land at Kalorama, they rather fancied the idea of having a donkey and when informed by friends about one available at Sandon, agreed to drive there one weekend. In the process of collecting Doreen, they also fell in love with the beauty of the area and quickly decided that this was where they wanted to live. The decision wasn't a tough one to make as Trefor had been battling with a lack of electricity in his studio which made work impractical, and the damp weather which was affecting his health.

Six weeks later, when a cottage became available for rent at Sandon, Doreen was back where she started.

Shortly after they moved to Sandon, a miners cottage at nearby Strangways came up for sale and so began a new era for the Prest family. Overlooking the fertile flats forged by Jim Crowe Creek and Loddon River, the cottage was one of many relics left over from the gold rush of last century, but the yield of gold from the valley was so high that the area was still being dredged until recently. More important than gold, the Prests' new property had a gentle rise overlooking the cottage which was an ideal site for Trefor's workshop, but before the family became absorbed in building the studio, they needed to make the cottage habitable. "It was pretty basic when we first came here," Trefor says.

The original cottage was built around 1890 and later had two lean-tos added. There was only an outside toilet and no bathroom, so these became the Prests' first priority. With the assistance of a friend, Trefor has done most of the work himself including massive renovations and additions to the rear of the cottage which, he says, are "still going on" to accommodate his growing family of Sam, 17, Tegwen, 15, and Bonnie, 13.

From the road, the Prests' cottage looks much like it might have in 1890, but the renovations and additions include three arched windows which are impressive features on the north wall, a second level built from cedar and blending in with the brick work beneath and a wide cool verandah which beckons on a hot day.

Trefor's studio looks as if it has been there for the past century. Progressively built from second-hand galvanised iron, mostly salvaged from the Castlemaine Woollen Mill fire of 1981, it was later extended to include a gallery for his collection of pressed metal sculptures.

Trefor spends most of his time there, up the hill from the house and under the watchful eyes of Doreen, working on his metal creations and listening to his beloved opera music.

There is little left of the original garden with the exception of an exquisite pink rose which Belinda has been unable identify, the remains of a plum hedge which Trefor had to tame with severe pruning and two enormous cypress trees at the front fence which flagged the cottage's location for bygone visitors walking from Strangway's railway station. Additions to the garden include a young grove of elms, oaks and willow trees surrounding a small ornamental lake which has a waterfall and a flock of geese that defy all efforts to keep them away.

Trefor's artistic influence is evident from the galvanised steel sculpture which doubles as a letterbox in the gateway to the fire box in the dining room which is constructed from a recycled steel boiler. He believes that the use of steel, wood, brass stock and copper sheet salvaged from scrap metal yards adds interest to his sculptures. "Acting out his engineering fantasies," an art critic once said.

While Trefor has completed many engineering courses, including a welding certificate, it is his childhood memories of his seaside home in Wales and his love of stories from the sea and outer space which provide the basis for most of his ideas. A friend's yarn about a lifebuoy labelled "for those in peril" prompted one of his more interesting pieces, a glass case featuring a diver submerged in clear oil. Trefor is also influenced by nautical and aerial machines from bygone eras and his sculptures aren't just for looking at, they must be touched and experienced. A sculpture with wings that parody flight is manoeuvred by a handle and in another piece, compartments open to reveal a hidden aspect.

Pieces of Trefor's work have been sold to corporations, as well as the National Gallery in Canberra and galleries in locations as diverse as Newcastle and Launceston, yet he believes that he is still to reach a turning point in his career."Young artists often receive a lot of attention early in their careers, but after that you have to wait until you're 60 or 70 years old before your career picks up again," he says. "I hope that I don't have to wait that long."

More recently, Trefor has enjoyed the new experience of tutoring two days a week at Ballarat University. "It's a nice change to be surrounded by people who appreciate what I do in a professional sense," he says. And yet he is also glad to get home and participate in "a bit of domestic life".

All three of Trefor and Belinda's children show artistic tendencies and the studio also houses some of their work, but Trefor encourages them to make their own decisions on what to do with their lives.

"From my own experience as an artist, it hasn't been a dream run."

Since Doreen prompted the Prests to make Strangways their home in 1982, the family has extended to include Pinkie the rat, Hugo the ferret, Alfred the guinea pig, two dogs and a number of horses. Firmly entrenched in their rural lifestyle, it would take more than a Land Rover to move the Prest family now.

Craft Arts International No.34, 1995

MARITIME SCULPTURES

Evocations of an early machine age, crafted with an exquisite sense for materials, the maritime sculptures of Trefor Prest possess a reverie that defies their highly polished, finished outlook. Text by Henk Bak.

THE creations of Trefor Prest are reminiscent of bathyscaphes or bathyspheres, of deep-sea exploration, of the way in which shipwrecks grow by disintegration and quiet transformation, through corrosion and sedimentation, seaweeds and shells, in the dark depth of a seabed.

As a rule, Trefor Prest shapes and forms the elements of his compositions to his own specification: the work of a metalsmith and a toolmaker, mechanic and woodworker. Over the past 15 years or so the forms have evolved from structures to vessels, to composites of both; from the purely mechanical to an increasingly organic feel, with strong metabolic tendencies. The titles of the works have partly come as a reflection on the finished piece, partly as a motive developing through the work, as with For Those in Peril (1992) and Dogger Bank. The latter is the only piece that is mainly composed of timber.

The way Prest works with wood creates a fair amount of dust and ventilation problems, which he thus far has tended to avoid, although he has the equipment, fan and ducts, to face them. For the time being wood sits more comfortable in his work as a warm and enriching element incorporated into handles or vessel bodies, enlivening them with a touch of quiet charm.

Prest's own rare hints as to the meaning of his work allude to notions of "escape" and "nostalgia". His reticence is appropriate, for the work is quite capable of speaking for itself and words are not the language in which it speaks. His sculptures are distinctly sensuous. Anyone with a healthy sense of touch and balance, vitality and movement, warmth and sound, will have much to explore and to delight in. Modulations in surface texture, alternations in materials such as wood and metal, generate variations in tactile temperature, amidst an all-pervading warmth articulated through cooler elements. The pieces appeal to both the "material" imagination (Gaston Bachelard) as well as the "formal" imagination, and include warmth or temperature in the range of their aesthetic qualities — a possibility that the sculptor Joseph Beuys had been the first to explore with materials as diverse as copper, fat and felt.

The mechanical, automated or tool-like appearance of the sculptures, suggestive of the whizz and clatter of fast-moving parts, supplemented with the occasional suggestion of a sounding horn, creates a fine stillness around them. There are, indeed, some moving parts and one can experience some complex transmissions when trying them out, but these modest "real" sounds cause only tiny ripples in the atmosphere of stillness. These movable contraptions are fun, kind of gentle jokes; deceptively simple, like good comedy, playing down considerable input of effort and skill.

If a reviewer's first task is to intensify the viewing of the work, a second task may be to expand the viewer's context, thus uncovering some of the work's potential and its possible direction. In both cases the key to any reviewing lies in the work itself, even if references to other people's work and to the literature may be helpful in the clarification.

There are some affinities with the work of Geoff Bartlett and the late Anthony Pryor. One could try to classify Trefor Prest's work as post-Modern, Modern, constructivist or surrealist. (Ref. Max Ernst's The Elephant of the Celebes, 1921.) These may be valid ways of expanding the context for his work.

For the purpose of this elucidation it may be useful to adopt a different line of approach, for many viewers are intrigued by the "living" quality of these machine-like, lifeless objects.

If art does not copy things but makes them visible, tangible, audible and so on, then what Prest's sculptures manifest is what Michael Polanyi has called the "tacit dimension": i.e. the way we are present beyond the physical boundaries of our bodies, in our instruments and tools; for example, a blind person, at the top of his or her walking stick.

In seeking to explain life by purely physical and chemical laws, scientists tend to look for mechanisms, as they seem to represent the purely physical and chemical laws in action. What those scientists don't seem to realise is that mechanisms are explained by their purpose, not by physical and chemical laws.

Mechanisms and machines work in a margin of freedom that the laws of nature allow them. There are limits to what pressure, tension, torsion, friction, etc., materials like metals and wood, clay and glass stand up to. When a mechanism breaks down, it has transgressed one or more of these limits. Physical and chemical laws explain a machine's breakdown, not its function. A machine works through a purposeful use of its margin of freedom. Purpose is a category beyond the grasp of the physical sciences.

Purpose belongs to the realm of life, sentience and intentionality, i.e. culture. In a nutshell, this is Polanyi's classic exposure of science's blind spot for the cultural basis of mechanistic explanations of life.

A foreigner who was an absolute outsider to our culture and who knew all the chemical and physical laws of nature, would not be able to explain a wire, a handle, a vessel or a piston …. By getting to know our culture such a foreign visitor would start to understand how this culture uses Nature's margins to extend our bodies and our lives through tools and machines and to what purpose.

This brief excursion into the realms of theory and philosophy of science may help to enhance our appreciation of work such as Prest's: Without a clue regarding purpose, machines would remain a riddle, unsolvable in principle. Doubly riddling would be sculpture, as one needs to know purpose in order to transcend it. As a work of art, a sculpture transcends purpose. A sculpture in the form of a machine may be triply enigmatic, especially when some components of the "machine" are contrived to work with deliberate uselessness.

This three-step transcendence of physical/chemical law seems to convey a sense of life to them in the same way as their stillness seems to evoke movement and sound. In his earlier work this "organic" quality might have been latent (pure structures), and then interiorised in the second stage (vessel forms). At present it seems to have surfaced, emerging from their containing bodies (as in Our Lady of Troubled Waters, Art Fair, and Albion's Dream), or winding their way around those bodies like external intestines, in the way insects have their external skeletons (as in Sun God, Desire and Rope). In other works those surfaced "organs" seem to have externalised themselves into a position that clears the space surrounding the container body (as in Days of Hope perched on the peak of a cone, or Ship of Fools cradled in the open ribs of a boat's hull).

In For Those in Peril the organic body remains inside but is made visible through the windows of its lantern-like container body, whereas in Dogger Bank the container body is an elaborate piece of architecture, tower-like, shed-like, ramp-like, in which the ship hangs high and dry. Mainly made out of wood in this sculpture Prest plays with varieties of timber in the same way as with metal in his other work.

All mechanisms find their ultimate explanation in living organisms, the function of which they are extending: spades and hammers extend our hands cooking pots our bellies. Living organisms themselves embody our sensitivities, desires, feelings and aspirations: reverberating and resonating with them and reflecting them. In this sense, the title may not only convey an escape from a sterile culture of electronised technology, a nostalgia for the time when machines still embodied humanness in their tangible handles and intelligible transmissions, also suggest a timeless sense of machines as embodiement — from a personal to an individual mythology, from an individual artist's life story to the magic cauldrons of Celtic fairytales or the prophetic products of Ilmarinen's furnace in the Finnish Kalevala The concept of organprojektion was introduced by Ernst Kapp, over 100 years ago, in his philosophy of Technology: the idea that in tools and machines an organism projects itself outward. Mental projection, i.e. unconscious transfer of what lives in me as feeling or thought into the outer world, people, objects and so on, is a deep psychological concept, starting with Breuyer and Freud. Although both concepts of projection may be useful in an appreciation of Prest's work, the most valuable one is organo-projektion. Not only does it make sense of Prest's work up to now, but it also suggests something of its potential. In other words, we observe in the titles "mental" projections; condensations of what the maker sees in the work and passwords for the viewer to enter it. In the works themselves we see machines revealing their organic, human and cultural origins projections of a more objective kind.

In his recent exhibition called "Pinacotheca" at the ACAF Contemporary Art Fair in Melbourne (September—October, 1994), the works were seen removed from their aquatic element. Imagine them being lifted from the water, washed and shiny, dripping, causing rippling circlets to spread … it was no accident that Gaston Bachelard made his point on material imagination in a book on water. To this effect, a series of photographs of Trefor Prest's work emerging from and hovering above the water has been very helpful.

Henk Bak

Henk Bak is Senior Lecturer in History and Theory of Art, Faculty

of Art and Design, Caulfield/Frankston Campus, Monash University,

Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

REFERENCES:

Gaston Bachelard, Water and Dreams (1942), The Pegasus

Foundation, Dallas, 1903.

Transforming Art, Vol.4, No.2, 1994. Creativity. The Arts. Water

Haselbrook, NSW.

Michael Polanyi, The Tacit Dimension, Doubleday, New York, 1967

The Kaleia or Poems of the Kaleva District, compiled by Elias

Loennrot, Trans. W. Kirby, The Athlone Press, London, 1985

Georges Canguilhem, Machine and Organism, Incorporations,

Zone 6, Urzone Inc, New York, 1992.

"Tales From The Valley Below" 1978

In my early 20's, I walked into the National Art Gallery of Victoria (Australia), and saw this in the foyer. I immediately fell in love with it. Unfortunately I lost my note of who the sculptor was. Years later, thumbing through old Art in Australia magazines, I saw it again and made sure I kept the name this time, Trefor Prest.

Behind the local church in Richmond, Melbourne, was a gallery called Pinacotheca. The local minister, for some reason or another, had access to this gallery, and my family went in for a look. Lo and behold, more works of Trefor Prest's. I was beside myself. These were large pieces back then.

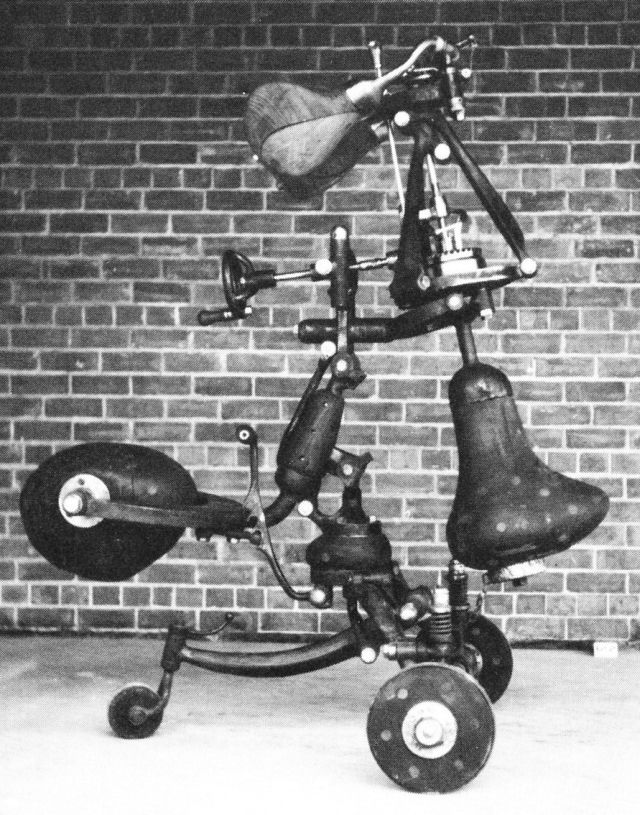

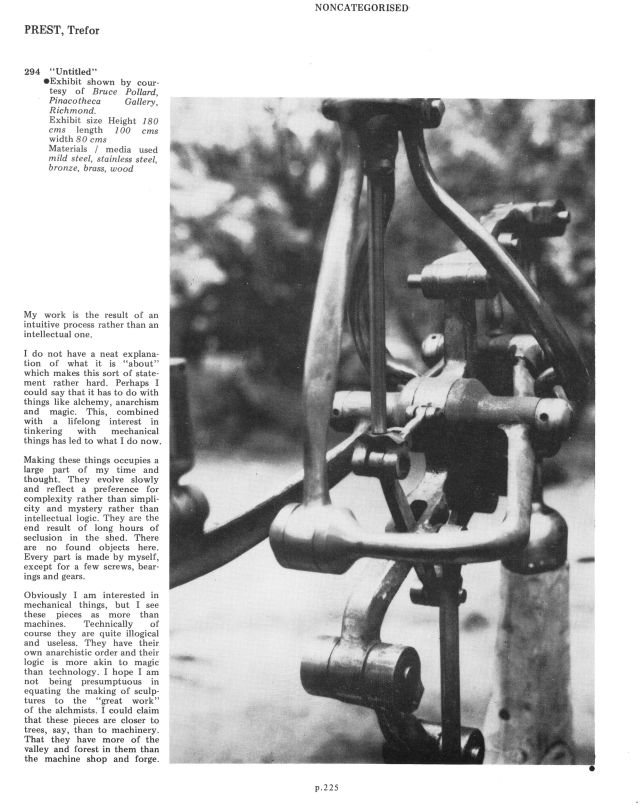

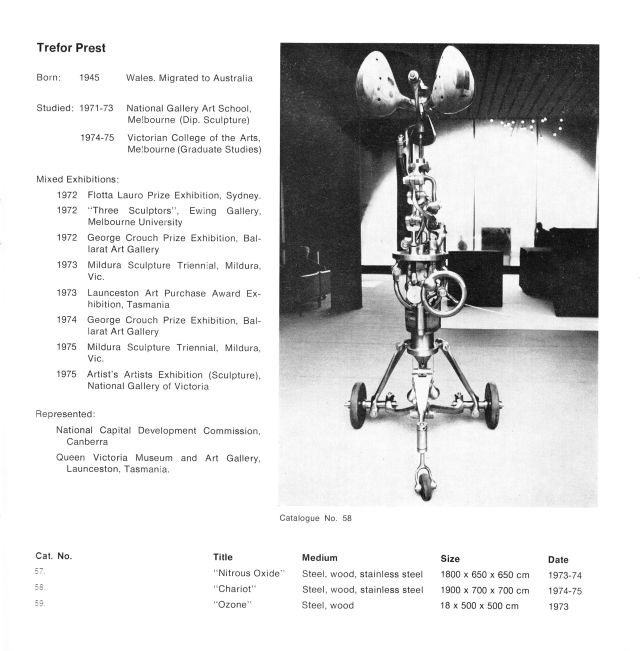

PREST, Trefor

294 "Untitled"

•Exhibit shown by courtesy of Bruce Pollard, Pinacotheca Gallery, Richmond.

Exhibit size Height 180 cms length 100 cms width 80 cms

Materials / media used – mild steel, stainless steel, bronze, brass, wood.

My work is the result of an intuitive process rather than an intellectual one.

I do not have a neat explanation of what it is "about" which makes this sort of statement rather hard. Perhaps I could say that it has to do with things like alchemy, anarchism and magic. This, combined with a lifelong interest in tinkering with mechanical things has led to what I do now.

Making these things occupies a large part of my time and thought. They evolve slowly and reflect a preference for complexity rather than simplicity and mystery rather than intellectual logic. They are the end result of long hours of seclusion in the shed. There are no found objects here. Every part is made by myself, except for a few screws, bearings and gears.

Obviously I am interested in mechanical things, but I see these pieces as more than machines. Technically of course they are quite illogical and useless. They have their own anarchistic order and their logic is more akin to magic than technology. I hope I am not being presumptuous in equating the making of sculptures to the "great work" of the alchmists. I could claim that these pieces are closer to trees, say, than to machinery. That they have more of the valley and forest in them than the machine shop and forge.

Other sites showing Trefor's sculptures – http://feralsportscarclub.net/Prest.html

Thankyou for gathering these articles on Trefor’s work together.