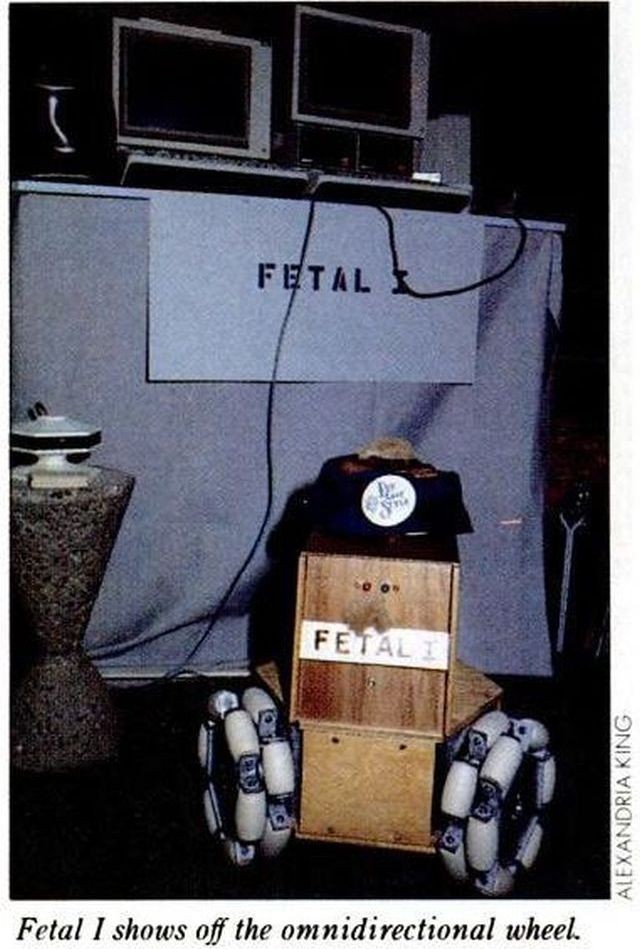

FETAL I had its major public appearance at the International Personal Robots Congress (IPRC) held in Albuquerque, New Mexico in 1984.

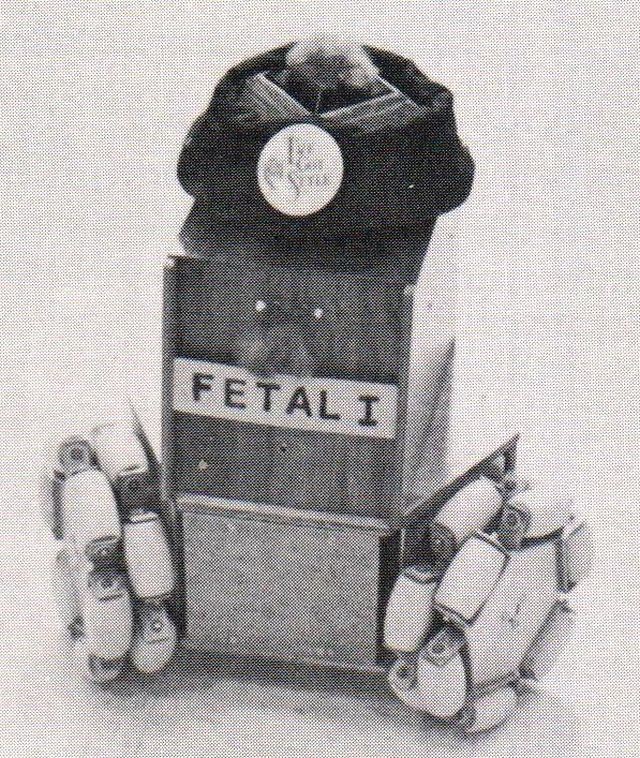

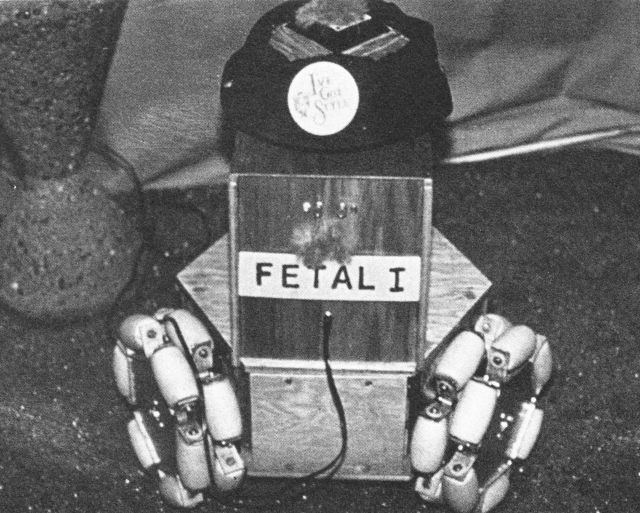

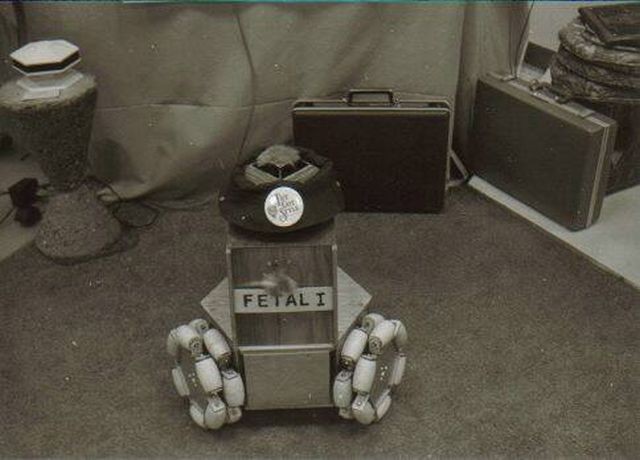

Fetal I, constructed by Bill La, is a three-wheeled vehicle capable of moving in any direction, A later prototype, Fetal II [no picture available], was presented a Golden Droid award at the 1984 IPRC.

FETAL I at the IPRC 1984. Images by Richard Moyle via David Buckley's Historic Robots.

IPRC-Robotics Age Aug 1984.

Sunday was the day everyone had been waiting for, the awards brunch, Nelson Winkless, the official historian for IPRC, acted as master of ceremonies. After his opening remarks and thanks to the many behind-the-scenes personnel, Nels got down to the most important part of the program, the presentation of the Golden Droid awards.

The Golden Droid awards were presented in three categories: the most entertaining going to Bruce Taylor for his robot Henry; the most useful being presented to Reza Falamak and his EZ Mower Robot; and the open award going to Bill H. T. La for his Fetal II [Ed. not shown.]. After the picture-taking and congratulations were over, it was back to the exhibition hall for the final afternoon of the show, Although Sunday's attendance was somewhat less than the two previous days, the enthusiasm was still evident.

Dr. Bill La with his wife.

Venture – Volume 6, Part 2 – Page 88

William H. T. La, 33, was a Vietnamese exchange student and maker of toys when he invented the Alexis while playing with an erector set. He found that by placing castings on three wheels, the wheels could move in any direction.

Patent information:

Source: Robotics Age, Feb 1984.

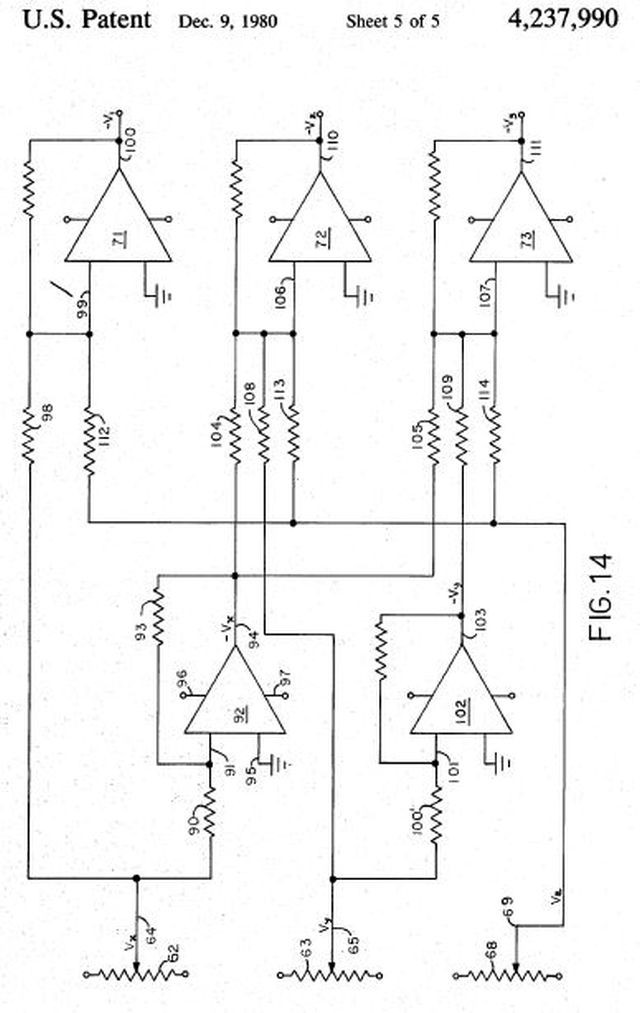

Publication number US4237990 A

Application number US 06/000,570

Publication date 9 Dec 1980

Filing date 2 Jan 1979

Inventors Hau T. La

Original Assignee Hau T

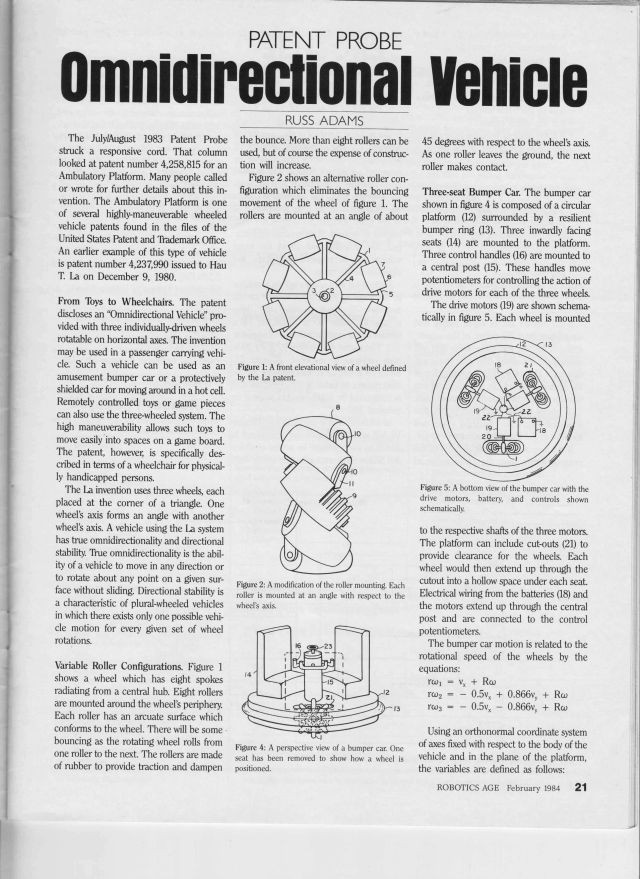

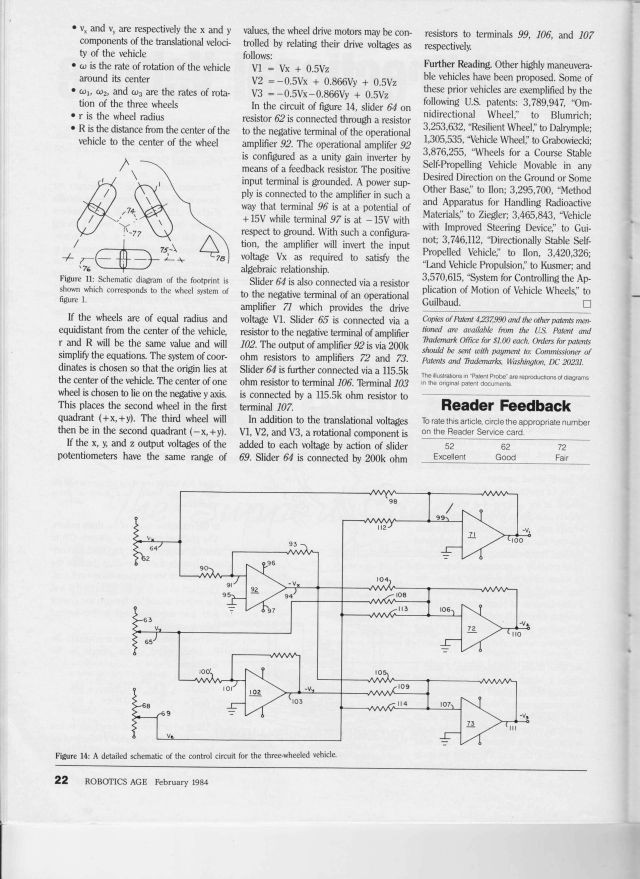

Omnidirectional vehicle

US 4237990 A

Abstract

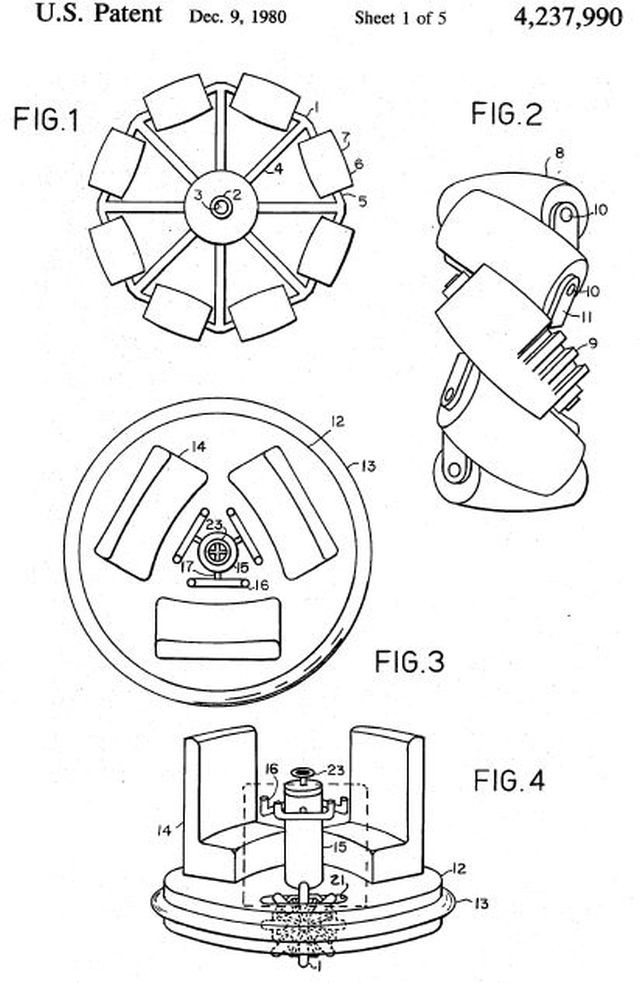

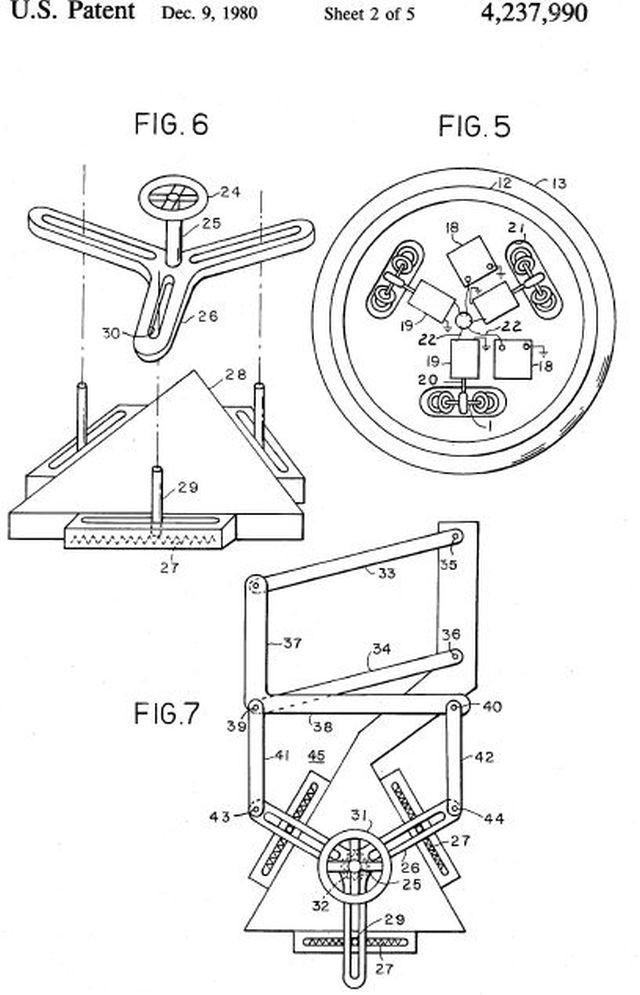

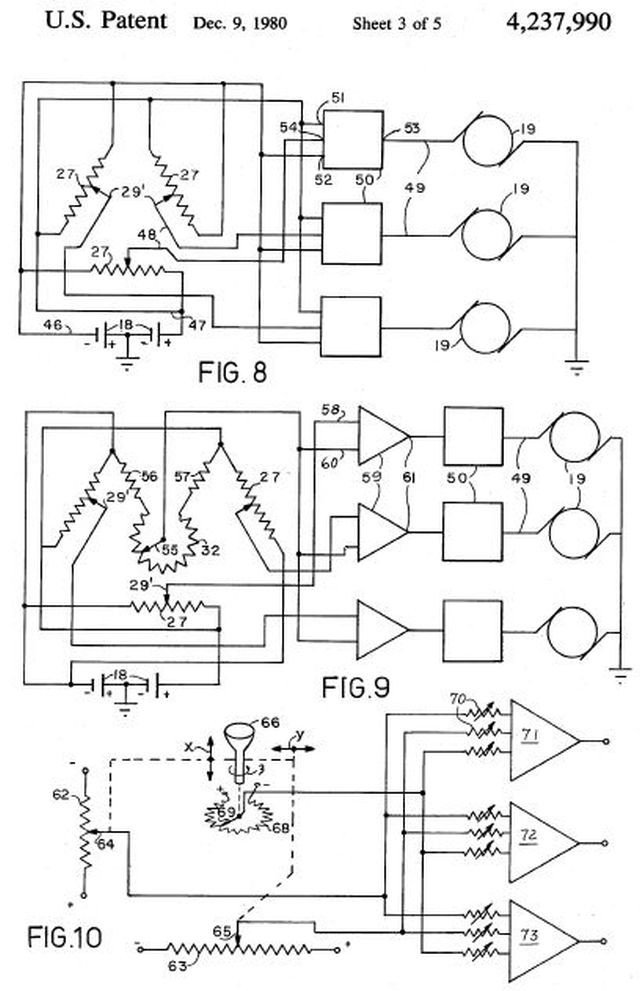

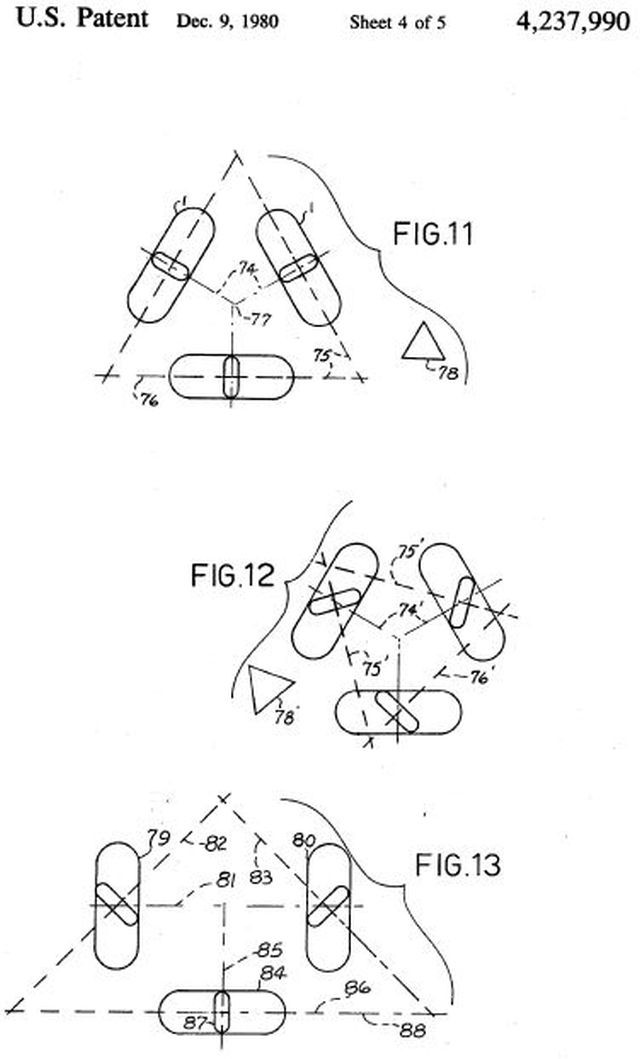

A wheeled vehicle provided with three individually driven wheels rotatable on horizontal axes. The wheels are disposed at the corners of a triangle. The periphery of each wheel is defined by a plurality of rollers rotatable on respective axes which are each at an angle to the axis of the respective wheel. The axes of three rollers, one for each wheel, when each such roller is in its lowermost position, form a triangle. Each roller axis may be at right angles or perpendicular to, or at 45 degrees to, or at some other acute angle to the respective wheel axis, and the triangle may be an equilateral triangle in a typical embodiment of the invention.

According to a preferred embodiment of the invention, no two of the wheel axes are aligned or parallel to each other. In a typical construction, the wheels are at the corners of an equilateral triangle and the wheel axes intersect at the center of this triangle. The vehicle may be driven over a surface, or it may be inverted and an object with a surface engaged on the wheel rollers may be moved with respect to the stationary "vehicle". Controls for motors driving the wheels of the vehicle are provided to produce rectilinear movement, rotational movement or curvilinear movement of the vehicle over the surface.

Alexis, the Omnidirectional Wheelchair.

An earlier prototype of the omnidirectional wheelchair.

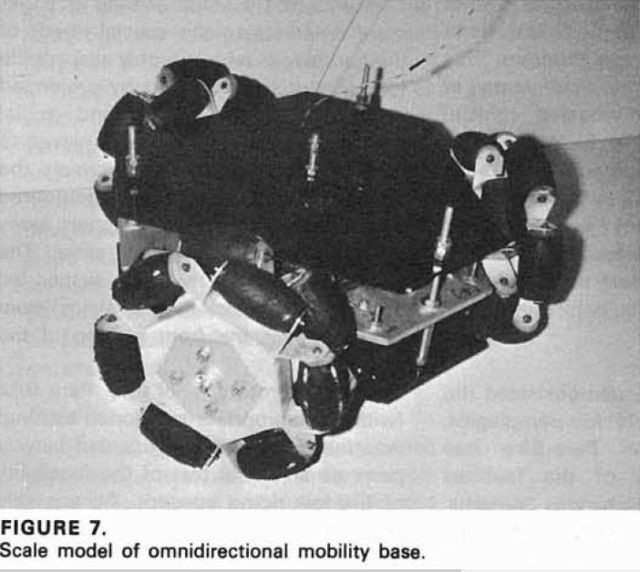

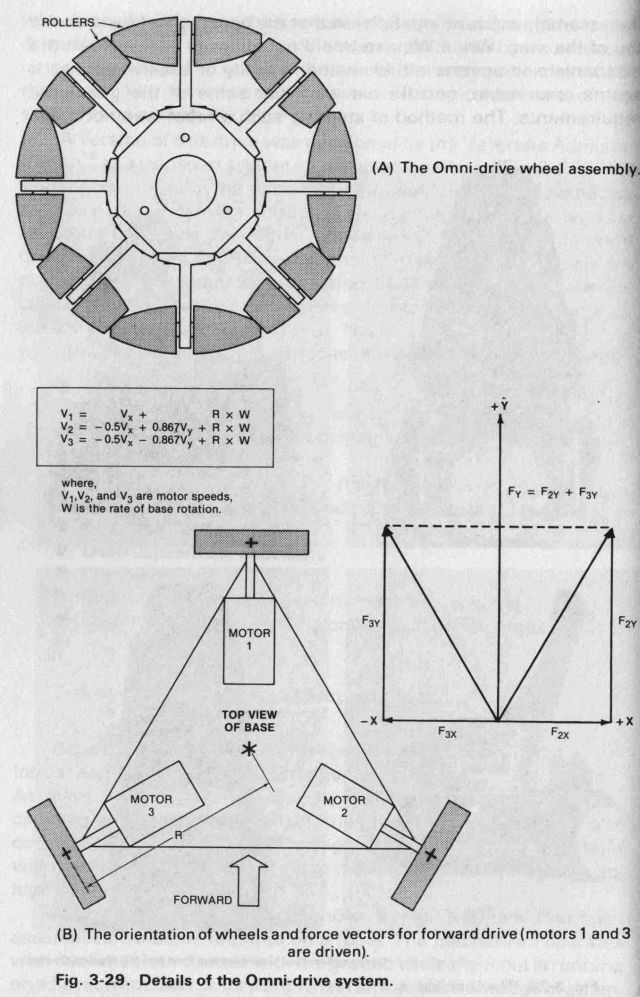

Source: Basic Robotic Concepts, John M. Holland, 1983

A version of this drive was developed by the Veterans Administration as a transport system for paraplegic persons (Fig. 3-28). This system powers only the axial motion of each wheel, allowing the smaller outer wheels to roll freely. The effect is that these rollers act as force translators. This effect can be seen for the case of forward drive shown in Fig. 3-29B. Notice that only the two rear wheels are powered for this maneuver and that their outward force vectors cancel. This scheme greatly reduces the complexity of the carriage, but some loss of traction will occur. The small diameter of the rollers will also cause difficulty on surfaces that are not perfectly smooth.

• Efficiency: Good

• Simplicity of Control: Excellent

• Traction: Good to fair (for single-axis drive)

• Maneuverability: Excellent

• Navigation: Excellent to fair (for single-axis drive)

• Stability: Fair to good depending on mounting

• Adaptability: None

• Destructiveness: Excellent

• Climbing: Poor

• Maintenance: Poor to good (for single-axis drive)

• Cost: Moderate (in production) to good (for single-axis drive)

Dr. William H. T. La is the inventor of the Alexis, at the V.A. Institute in Palo Alto. The Alexis is a nonconventional "smart" wheelchair that uses a system known as "metamotion", employing three independently motor-driven nonparallel wheels linked by an on-board computer. This feature, patented by Dr. La in 1980, allows the Alexis to move directly to any point on the horizontal plane by the rider's manipulation of a joy stick that sends an electronic signal to the computer that controls the directions of the three wheels. The Alexis also has a control feature that enables a rider unable to manipulate the joy stick to operate the Alexis by head motion. As a result, any rider of the Alexis, regardless of disability level, could make it "turn on a dime" and maneuver it in cramped spaces.

The world's most futuristic wheelchair was designed and patented by Stanford University in 1982. It's omni-directional wheels made it truly revolutionary for its time. It was named in honor of Kim Alexis.

The Evening Independent – Sep 24. 1984

'Alexis' the wheelchair called a significant step

As technology advances, entrepreneurs put it to use—quite often, to the advantage of victims of disease and infirmity, On this page, the focus is on a new computer assisted "sports car" wheelchair.

PAUL ENGSTROM

Knight-Ridder Newspapers

SAN JOSE, Calif, — Robert Smith slides into the $1,300 bucket seat of his sleek, computer-assisted wheelchair, fingers the control panel at his left hand and the joystick in his right, then zips off for a quick spin around a local shopping center,

At a top speed of 12 mph, the machine isn't exactly primed for the Daytona 500, But "Alexis," as Smith has dubbed this roadster-like tricycle for the disabled, which he helped design, enjoys advantages unknown to stock car racers.

At the shopping center, those advantages quickly proved themselves, Smith didn't swerve when shoppers stepped in his path because Alexis, unlike conventional wheelchairs, can move sideways as well as forward and backward.

The vehicle is part ballerina, too — it can pirouette within its own footprint, whereas ordinary wheelchairs have a turning radius of about one yard. This gives Alexis the kind of maneuverability that is critical in tight spaces, such as between racks of clothing in apparel stores or between a desk and wall at the office.

And belying the notion that wheelchairs will always be drab, pitiful contraptions, Alexis got some admiring glances as it sidestepped and twirled for the curious shoppers, A list of the world's 10 sexiest machines, Smith knows, wouldn't include present-day wheelchairs — an image he hopes Alexis will shatter so that, eventually, paraplegics and others can pride themselves on what may be their only means of powered transportation.

Indeed, Smith was thinking of Kim Alexis when he christened the wheelchair. She's the stunning blonde who last year modeled a red bathing suit in Sports Illustrated's swimsuit edition.

Smith, 24, who graduated from Stanford University in 1982 with a master's degree in mechanical engineering, and four others designed and built the futuristic wheelchair over a six-month period at the Veterans Administration Rehabilitation Research and Development Center in nearby Palo Alto, Tim Prentice, a high school student at the time, provided rough sketches of what was to become Alexis.

Smith's goal was to innovate, to build a machine that would include a Zilog Z-80A microcomputer to adjust the speed of the three independently powered wheels so the vehicle would move in precise directions at precise speeds. The microcomputer performs this command-and-control loop 20 times a second.

"It's almost as if you were going to build a sports car," Smith said of his design approach. "You can either soup up a Chevy Nova or start with a clean sheet of paper and design a Corvette."

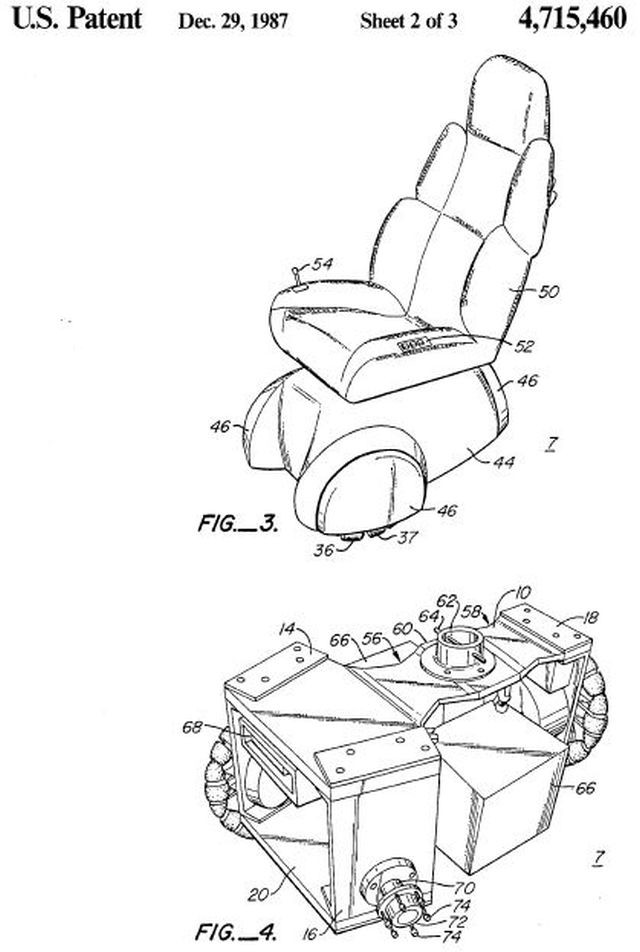

Each wheel consists of eight natural-rubber rollers instead of treads, allowing the wheelchair to travel in all directions without any drag. The Boeing Co, owns the patent on this design for its shop carts.

The wheels — two in front and one in back —and motors are concealed by rounded fiberglass covers adorned with a red racing stripe. Adding to this airstreamed, classy look is the removable bucket seat manufactured by Recaro, the type commonly found in sports and racing cars.

"Actually, I'm kind of tired of that designs" Smith confided, "It looks like a vacuum cleaner,"

Perhaps, but Alexis doesn't sound like one. Its advanced electronics create very little noise. Moreover, the microcomputer won't let Alexis travel so fast that it tips over, and because all three motors are identical, unlike conventional models with left and right motors, parts are interchangeable.

That's important because wheelchair manufacturers don't stock many spare parts.

International Texas Industries of San Antonio has purchased the patent on Alexis and will manufacture it in Wichita, Kan. The first delivery is due Dec, 31. Initially, 500 of the wheelchairs will be test marketed only in the San Francisco area, so engineers here will be able to easily spot and correct any glitches.

The standard model will sell for $4,000 to $5,000, Smith estimates. Wheelchairs currently on the market, which is dominated by a company called Everest & Jennings, vary from $4,000 to $15,000, depending on the number and type of accessories the buyer needs.

Experts in and out of the VA agree that Alexis marks a significant step in wheelchair technology.

"This is the single most important contribution to mobility of the disabled since electric-powered wheelchairs were introduced," said Larry Leifer, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at Stanford University and director of the VA's research and development center.

"Most offices are inaccessible to wheelchairs. We expect Alexis to give (disabled) people a wider choice of places to live — without modifying that house, which is very expensive — and we expect it to give them broader employment opportunities."

David McGowan, executive director of the Adult Independence Development Center in Santo Clara, agreed.

"I'd say it's a rapid evolution," McGowan said. "It would be a significant change.

"Although federal law mandates that new projects be accessible to the disabled, we live in a reality where most buildings are not accessible. Doorways and hallways are not wide enough, for example. That would make (wheelchair) maneuverability critical."

The VA, according to McGowan, is at the forefront of such innovations because of the financial resources available to it.

As with any new mechanism, development of the Alexis prototype has fostered its share of headaches. Today, the wheelchair — itself disabled — sits in Smith's cramped laboratory near the VA Medical Center waiting for a new joystick. The original throttle was much too stiff for the kind of fingertip control for which Smith is striving.

In addition, the two fiberglass and nylon chassis plates began showing immediate signs of wear, forcing a switch to pure fiberglass to ensure durability while still offering a smooth ride. Another problem was getting parts: Smith often found that, because of the hospital environment, drugs and toilet paper seemed higher on the VA's list of items to be ordered.

The test pilot who puts Alexis through its' paces is Peter Axelson, 27, another mechanical engineer at the research and development center. Axelson lost the use of his legs eight years ago when he fell 180 feet while learning to rock climb as an Air Force cadet.

In subsequent years, he founded Beneficial Designs of Santa Cruz where he designed the sit ski, similar to sled.

"The initial sense of being able to move in any direction in Alexis is incredible," he said. "That's the most profound feeling, I believe that most people would get into Alexis and not try to move in any direction but backward and forward because moving sideways is so unusual."

The wheelchair negotiates tight indoor spaces better than it does curbs, hills and other outdoor obstacles. Yet, all devices have their limits, and Alexis is no exception, Axelson said.

"It's like the difference between a long distance runner and a dancer, Alexis is agile."

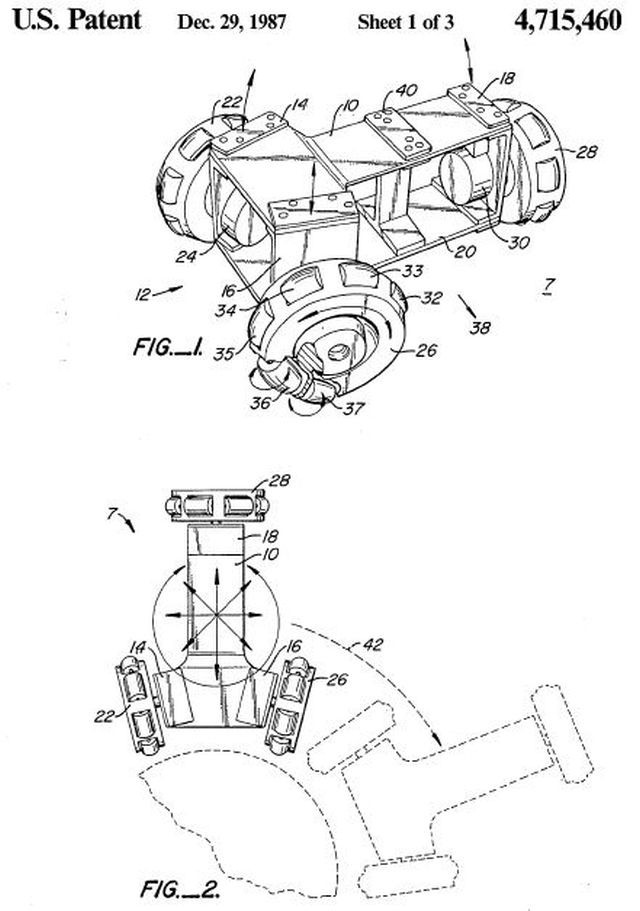

Patent information:

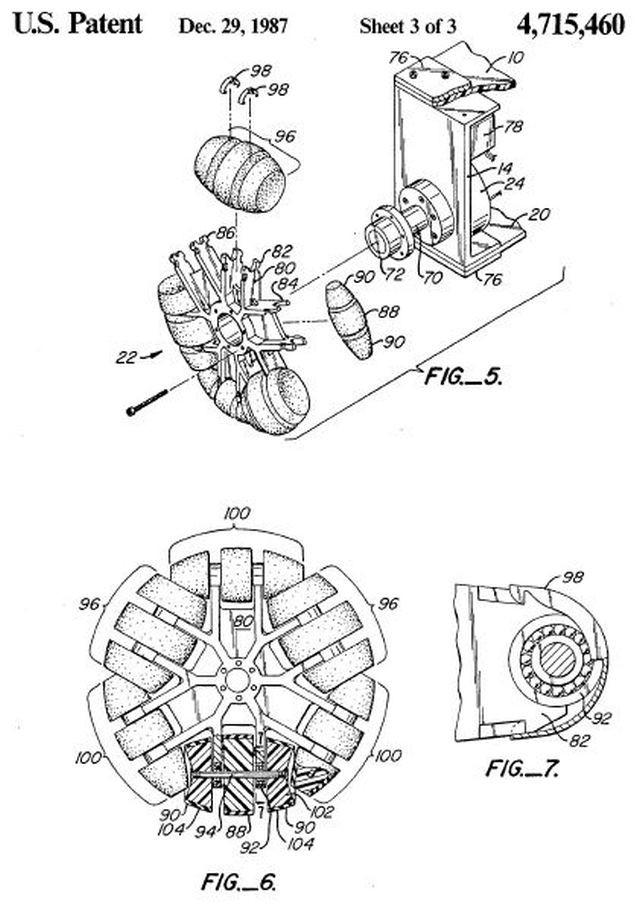

Publication number US4715460 A

Publication type Grant

Application number US 06/673,965

Publication date 29 Dec 1987

Filing date 20 Nov 1984

Also published as EP0201592A1, WO1986003132A1

Inventors Robert E. Smith

Original Assignee International Texas Industries, Inc.

Omnidirectional vehicle base

US 4715460 A

Abstract

An omnidirectional wheelchair base 7 includes upper 10 and lower 20 flexible base plates held in spaced-apart alignment by a pair of front supports 14 and 16 and a rear support 18. A pair of front wheels 22 and 26 are provided, each mounted on the front supports 14 and 16, respectively, and each having an axis of rotation wherein the angle between the axes of rotations of each of the front wheels is less than 180°. A rear wheel is mounted on the rear support and has an axis of rotation less than 180° from each of the front wheels.

Publication number WO1986003132 A1

Publication type Application

Application number PCT/US1985/002281

Publication date 5 Jun 1986

Filing date 19 Nov 1985

Also published as EP0201592A1, US4715460

Inventors Robert E Smith

Applicant Int Texas Ind Inc

Alexis Wheelchair – Last word:

Alexis is an innovative electric wheelchair using a "wheels within wheels" design. It is unique in that it can turn in its own footprint and move sideways. The Rehab R&D Center licensed Intex Industries to make Alexis commercially available in 1987, and Intex made 40 pre-production units for field trials in the San Antonio area. During subsequent redesign efforts, the company filed for bankruptcy, preventing further commercialization at the time.

From the video blurb: Unfortunately, Alexis never made it to market because Jon King, Intex CEO, embezzled millions of investment capital. He was later convicted and spent 10 years in federal prison for his crime.

Mobile Vocational Assistant Robot (MoVAR): 1983-1988.

Overview of project

The MoVAR project used a unique, patented, 3-wheeled omni-directional base with a PUMA-250 arm mounted on it. It was desk-high and designed to go through interior doorways (see Figure 2). All electronics and power components for the motors and sensors were mounted in the mobile base. A telemetry link to a console received commands and sent position and status information. The mobile base had a bumper-mounted touch sensor system to provide autonomy in the face of obstructions, a wrist-mounted force sensor and gripper-mounted proximity sensors to assist in manipulation, and a camera system to display the robot's activities and surroundings to the user at the console. The robot console had three monitors: graphic robot motion planning, robot status, and camera view. It had keyboard, voice, and head-motion inputs for command and cursor control, and voice output.

Omni-directional mobile robot called MoVAR.

Figure 2: MoVAR robot base with instrumented bumpers and joystick; the PUMA-250 carries a camera for remote viewing, a six-axis force sensor and gripper with finger pad-mounted proximity sensors. A wireless digital link allows the mobile base computer to communicate with the user console. A later phase of this project added instructable natural language input capability, coupled to an internal world model, so that typed-in commands such as, "move to a position in front of the desk, and move west when the bumpers are hit" could be executed. Path planning was not a targeted research area for this project due to the many other research groups active in this domain.

This project was stopped in 1988 when VA funding was terminated. The hardware and software were subsequently transferred to the Intelligent Mechanisms Group at the NASA Ames Research Center (Mountain View, CA) for use in the development of real-time controllers and stereo-based user interfaces for semi-autonomous planetary rovers.