Prosopographus

Selected extract from the full post by Patrick Feaster here.

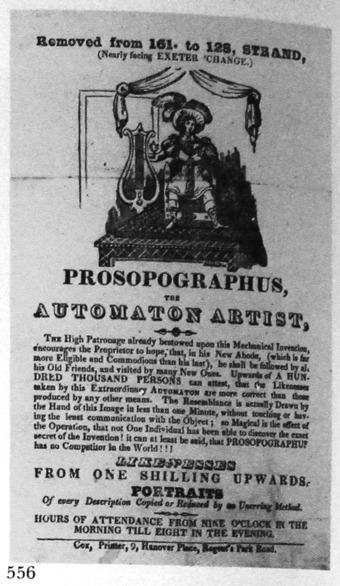

Between 1820 and 1835, a machine was exhibited around Great Britain that was advertised as taking people’s portraits by strictly automatic means. Someone had only to pay a shilling and sit perfectly still next to it for the space of a minute to obtain a likeness alleged to be more accurate than anything a living artist could have drawn. The machine relied on principles very different from those of photography, first introduced to the world via the daguerreotype in 1839, and its portraits didn’t anticipate the photographic portraits of later years in any technical sense. However, they did anticipate them quite closely in a cultural sense. As far as subjects were concerned, they might have gone to get their pictures taken by this machine in 1825, and again by a photographic camera in 1845, without perceiving any fundamental difference between the two experiences. In both cases, they would have been told that their likenesses were being captured automatically, without the mediation of a human observer, although they might still have paid extra for someone to touch up the results afterwards or add color to them. The earlier machine went by the name of “Prosopographus, the Automaton Artist,” and it produced silhouettes—thousands upon thousands of them, if reports from the time are to be believed. I was recently fortunate enough to acquire one, which is what prompted me to pull together the following account.

In appearance, Prosopographus was a miniature android figure dressed in fancy Spanish costume, shown above as illustrated on a period handbill. I’ll refer to it here myself as “it,” but contemporaries generally anthropomorphized it as “him,” consistent with the grammatical gender of its Greco-Latinate name: Prosopo- (“face”) -graph- (“writer”) –us (second declension nominative masculine ending). It held a pencil in its hand, and when someone sat down next to it, it would use this pencil—within full view of spectators—to trace an outline of the person’s profile. The process was described variously as taking less than a minute, half a minute, or less than half a minute, but subjects had to hold perfectly still during that time: “The least movement on the part of the sitter will occasion the Automaton to shake his head, and the operation of taking the outline to be recommenced. Advertisements emphasized that this work was carried out “without even touching the Face, and indeed “without touching, or having the slightest communication with the Person. Daylight wasn’t necessary either, patrons were assured, so that likenesses could continue to be taken after sunset. The proprietor never revealed the specific process used to capture people’s profiles, but it was claimed to be wholly mechanical, and hence superhuman in its accuracy. Thus, Prosopographus was billed as “performing more perfect resemblances than is in the power of any living hand to trace, and as “so contrived that by means of mechanism it is enabled to trace a more accurate and pleasing resemblance of any face that may be presented than could be produced through the agency of any LIVING artist whatever.

The basic portrait to which every visitor was entitled by default seems to have consisted of the profile painted in black, and some later advertisements specified that this included glass and a frame. For a surcharge, however, the profiles could also be cut out, shaded, bronzed, or done up in full color, as well as mounted in a fancier frame, at prices up to thirty guineas if anyone cared to pay that much. The result, in any case, was something visually indistinguishable from a conventional silhouette portrait of the period.

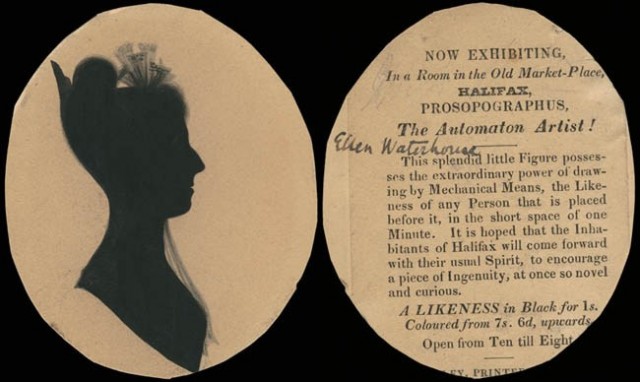

And that complicates our present ability to identify surviving specimens of Prosopographus’s work. According to Profiles of the Past, a website dedicated to the history of British silhouette portraiture, “very few silhouettes [by Prosopographus] are known today,” even though countless thousands are said to have been taken. Technically, however, what’s rare is a silhouette that can be attributed to Prosopographus because it’s labeled that way on the back. The few reported types of Prosopographus trade label are linked to just a few exhibition venues, so it may be that silhouettes taken in other places weren’t labeled, making them impossible to tell apart from “ordinary” silhouettes. For all we know, nearly all unlabeled silhouettes of the 1820s and 1830s might be the work of Prosopographus, which would make them extremely common. However, it’s only when there’s a label that we know for sure what we have.

The Prosopographus portrait I recently acquired is one of those with the Halifax trade label and promotional text on the back, augmented by a handwritten inscription identifying its subject as Ellen Waterhouse. The silhouette itself is a likeness of the basic type that was thrown in free with the price of admission: the profile painted in black, with just a few embellishments added in the same color to represent hair and veil.

See the full post by Patrick Feaster here.