SOLARIS – Submerged Object Locating And Retrieving/Identification System is a vehicle built by Vitro Laboratories for the U. S. Navy.

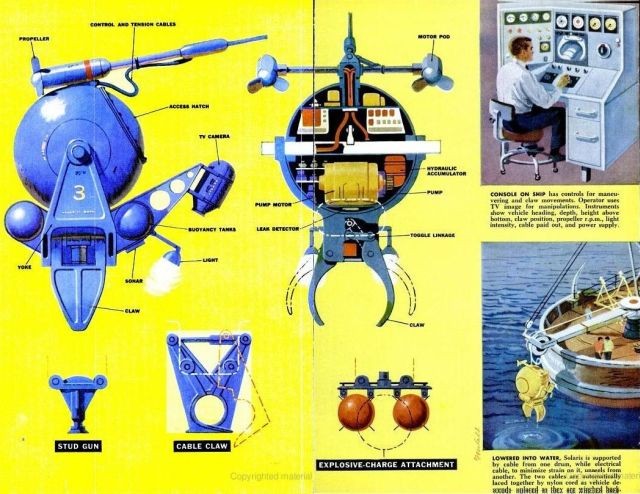

It can be used down to 650 foot depths and is controlled by a surface vessel through a cable. A toggle action claw is attached to the underside of the vehicle. It is designed to clamp cylindrical objects such as nose cones, torpedoes and mines. The claw is designed to retrieve objects weighing up to 5000 pounds in water. The claw is hydraulically operated through a toggle linkage. The over-center locking action of the toggle linkage provides maximum clamping pressure while minimizing the possibility of accidental release. SOLARIS can be fitted with different claws for special tasks. A servo valve controls the hydraulic power for the claw. A fifteen horsepower electric motor drives a hydraulic pump, rated at 3000 psi, which supplies the power for all the equipment on the vehicle. A TV system is used for viewing the undersea environment.

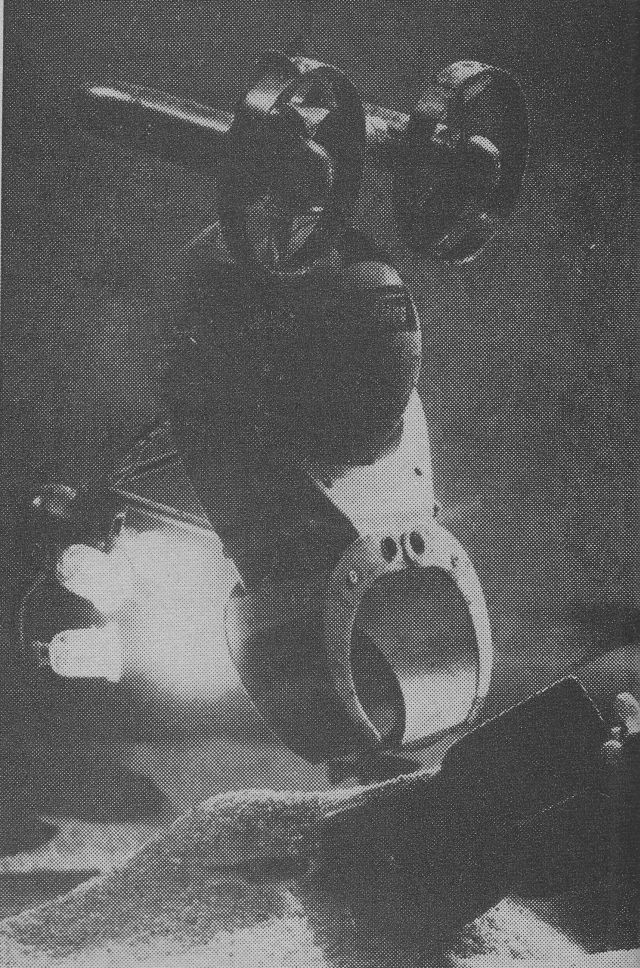

WORKING MODEL in photo above shows propellers for maneuvering, claw for grasping, and octopus-like body that houses electric motor to power both. Prototype will descend 850 feet, far deeper than human divers; later versions of Solaris will go down into the ocean as deep as two-fifths of a mile.

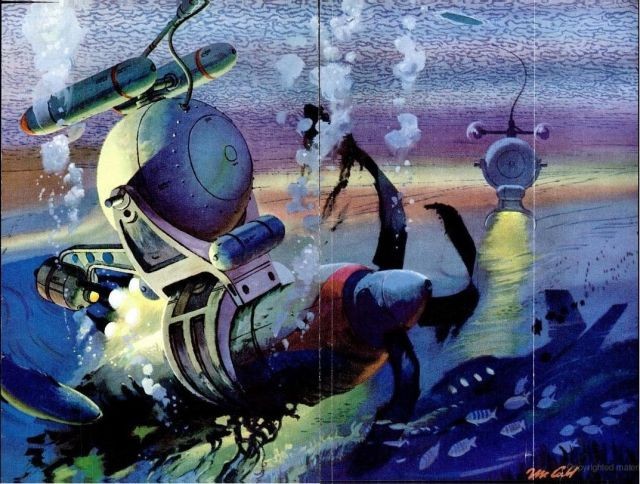

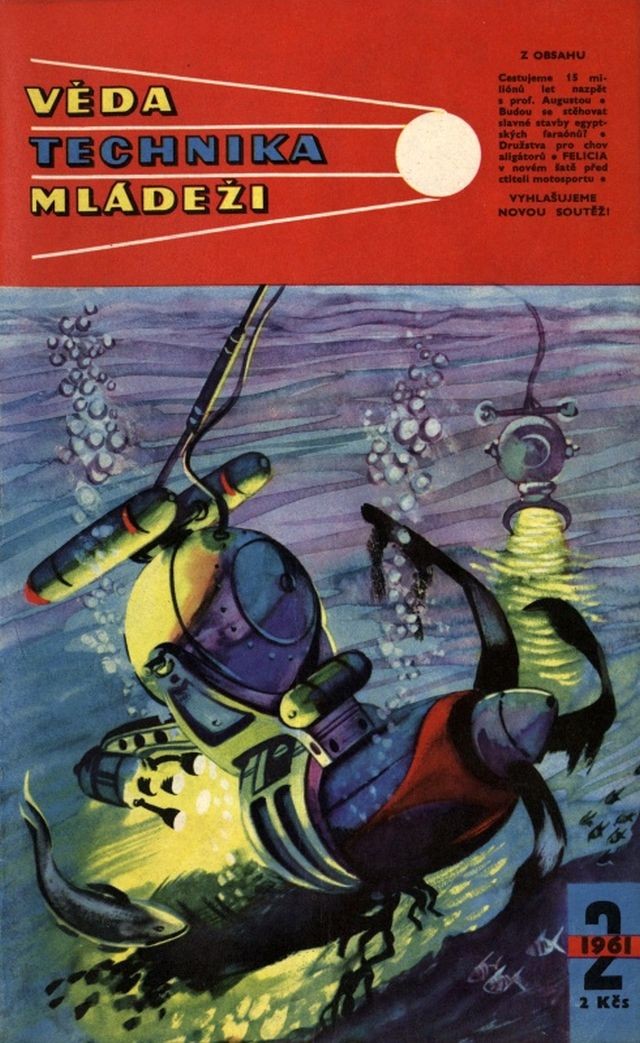

PAINTING IN FOLDOUT AT RIGHT [above] depicts Solaris at work salvaging wrecked plane—one of its many possible missions. See reverse side of foldout [below] for Solaris' various components and how the huge robot will be controlled from operator's console on the surface.

Mechanical Crab to Search Ocean Depths [Source: POPULAR SCIENCE, JULY 1960]

With an arm 2,000 feet long, TV-camera eyes, and a claw that can clamp onto a 2 1/2-ton load, the giant robot Solaris is a treasure-hunter's dream come true

By Devon Francis

DRAWINGS BY BOB McCALL

SOMETIME late this fall, a U.S. Navy boat in Puget Sound will drop overside, on a couple of cables, one of the strangest contraptions ever lowered to the ocean's depths. On its top will be a brace of propellers, at its middle a sphere, at one side a television camera flanked by lights, and on its bottom a claw.

The thing will be called Solaris. It will be the underwater treasure-hunter's dream come true.

Imagine sitting high and dry on the deck of a boat, and having at your command an arm more than 2,000 feet long to pick up whatever suited your fancy from the ocean floor —plus eyes to scan thousands of square yards of it.

Now under construction in Silver Spring, Md., for experimental torpedo recovery for the Navy, Solaris will be unmanned. In prototype, it is designed to descend to 650 feet, but it can be adapted to go down as far as two-fifths of a mile. That's 1,750 feet below the average safe working depth of a human diver.

Solaris is designed to do everything that a human diver can do, and more.

The propellers are for maneuvering. The sphere is the power unit. The TV camera gives underwater eyes to an operator aboard the launching ship. The claw is for retrieving anything that the operator wants on the ocean bottom—including sunken treasure.

Solaris (Submerged Object Locating and Retrieving/ Identification System) is versatile. It can go exploring, covering 1,400,000 square yards of ocean floor at a depth of 2,000 feet.

It can perform such prosaic tasks as inspecting channel bottoms, ship keels, bridge pilings, and submarine cables. It can clamp and bring to the surface objects weighing as much as 2 1/2 tons. It can place explosive charges, and then back off and detonate them.

One of its possible uses is recovery of pieces of rockets fired from Cape Canaveral and destroyed in flight because of deviation from course. Skin divers have to do this now.

The Vitro Corp., which is building Solaris to specifications outlined by Jack Green, project engineer at the Naval Torpedo Station, Keyport, Wash., knows it can perform all these duties because a preceding device already has demonstrated it. What might be called the daddy of Solaris was developed, also, for the Navy. Its missions are classified.

One of the two cables is the lifeline of the snoopy Solaris. This cable lets it down and pulls it up. Solaris' second cable is its nervous system. Through this, the operator topside issues commands for the thing to crawfish this way and that, to rise a bit or descend, to clamp onto a prize, to drive studs into steel plating, or to plant explosives.

The second cable also carries current for lights that illuminate the inky reaches of the deep, and it transmits the TV signals to a screen so the operator can see what he's doing.

Sitting at a console, the operator taps the second cable for information on heading, depth, height above bottom, propeller r.p.m., amount of illumination, and what Solaris' claws (or one of its substitute fitments) are up to.

That second cable, carrying the electrical lines, must be strong enough to take some tension, yet flexible enough to bend and twist while the vehicle is scrounging around on its boggle-eyed missions.

The sphere (a sort of octopus body inside Solaris' working ganglia) houses a 10-horsepower electric motor. It turns a hydraulic pump that supplies power not only for propulsion but also for the claw. To keep everything shipshape, the watertight sphere contains a leak detector and depth-measuring sonar.

How is works. To maneuver the vehicle, the operator has only to turn on the propellers and vary their speed. They are driven hydraulically through gearing that is essentially like an automobile differential.

The first cable is only a leash. Under the thrust provided by the propellers, Solaris strains against its hold. That's the secret of the depth control. The propellers' pitch can be varied to increase or decrease the thrust. Balancing off that thrust against the pull of the leash controls the height of Solaris above sea bottom.

The forces involved are the same as those in water skiing—with enough tension on the towing line, a skier planes on top of the water. When the tension drops the skier sinks.

The depth control is mostly automatic. The operator at the console on shipboard knows the topography of the ocean floor and at what depth he wants Solaris to operate. He turns a knob to get proper propeller thrust against cable tension.

Inside Solaris' sphere is a simple strain gauge to measure the pressure of the water. If the height isn't right, a signal travels back along the electrical cable to a servo motor on a winch that the leash-cable wraps around. The servo motor boosts or decreases tension on the leash-cable, as the situation demands.

But what if the console operator discovers on his TV screen that Solaris is on the brink of an ocean-floor trench that it must get into to do its job? The operator simply feeds a signal to the strain gauge that, in effect, reduces its sensitivity. The gauge telegraphs the motor winch, the cable tension is reduced, and Solaris drifts down into the trench.

Through the second cable also flow console commands for maneuvering right or left by changing the pitch on one propeller or the other.

It was Vitro's success in designing the second cable that led to the idea for Solaris. The company produced a torpedo for the Navy that trailed a long control cable behind it when it was shot from its tube. Directions fed through the cable to the torpedo's steering mechanism guided it precisely to its target. Solaris was a logical adaptation.

The Vitro people see no end of usefulness to Solaris. As a seeing-eye robot below the waves, it could discover a new shrimp bed, examine a faulty ship's propeller, or—who knows?—even retrieve long-sunken chests of Spanish doubloons.

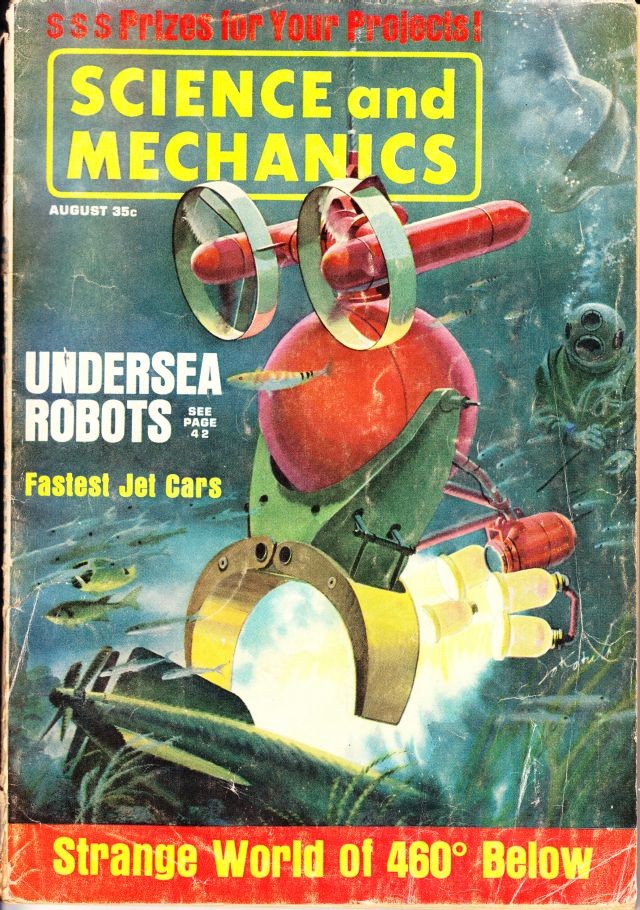

UNDERSEA ROBOTS By JOHN KRILL

Depth hidden ocean secrets may someday be an "open book" to scientists through further development of machines that are already performing scores of impressive underwater functions……..

Shown on the cover and on page 44 of this issue of S&M is the Vitro Corporation's SOLARIS, a claw-equipped robot, at work recovering a torpedo at a depth of 1620 feet.

Solaris has propellers that are driven at a constant speed of 420 rpm. By varying the pitch of the propeller blades, ship-board operators can adjust the thrust of each propeller from 250 pounds positive to 200 pounds negative. It has a maximum forward speed of about three mph after overcoming the drag of its lengthy connecting cables.

Source: Holland Evening Sentinel 18 July, 1960

MECHANICAL CRAB — An extremely facile device to retrieve spent torpedoes, small missiles and other metallic debris from the ocean floor is being perfected for the government by a Washington scientific laboratory.

Named the "Solaris," the device weighs 500 pounds, but can lift objects weighing up to three and one-half tons from the ocean floor. Its key piece of equipment is a television camera that enables operators on surface ships to "see" what lies in front of the device as it traverses the ocean floor at about 1 1/2 knots.

Solaris is equipped with a variety of "claws" for holding objects. It can pick up a spent torpedo, a missile casing or underwater pipes. It can also plant explosives and even fire a connecting stud into an unwieldy object so a cable can be attached.

An electro-magnet can be attached for gathering scrap metal and there is a grapple for netting. There are brilliant lamps that can be used to chart the ocean floor or help inspect underwater operations.

Work on the device has cost the government many thousands of dollars, but it is expected to pay for itself many times over.

See other early Underwater Robots here.