Robots on your doorstep (a book about thinking machines)

Nels Winkless, Iben Browning – 1978 – 178 pages

Yogi is Smarter than the Average Bear

…It is not widely remembered that Man has been the standard draft animal for most of "historical" times, quite apart from prehistory. Only very late in the game, during the Middle Ages, did the horse collar come into use in Europe, allowing the energy of the horse to be applied efficiently to ordinary agricultural tasks like plowing. Even today, human beings draw plows in large areas of the world. Harnessing animal energy was a major technological step for people.*1

When the industrial revolution came about, its major feature was the harnessing of non-animal power. Yes, waterwheels and windmills had been around for some time, but steam power was more predictable, more reliable, more controllable. We have found many ways to harness and apply energies that are not produced by animals.

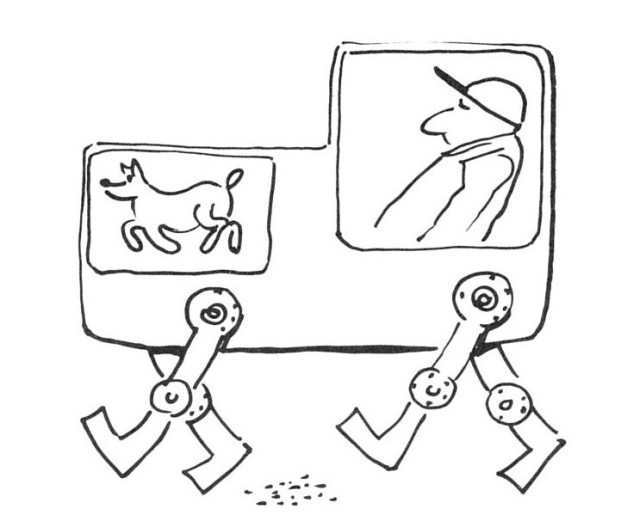

Oddly, we have not advanced much in the art of combining animal intelligence with non-animal energy. Machines tend to be operated by human beings and, while this may use animal intelligence under our broad definition, we have in mind animal intelligence other than human. For example, Bell Aircraft was intrigued but baffled by a proposal that lben Browning and Larry Bellinger laid out two decades ago [circa 1958] for a "Dog-Mobile."

The notion was that vehicles like trucks really consume too much human intelligence for efficiency. It seems a shame to waste the attention of a trained man on piloting a truck, just as it seems a shame to waste two trained men on piloting a bomber. Trucks might better be driven by reliable, adequately intelligent animals like dogs.

The problem is not that dogs are dumb enough to run into each other or fall over embankments, but that trucks have been designed for people to drive, not dogs. The movements of a truck don't feel familiar to a dog and the techniques and logic of steering and controlling speed are more than the average dog can manage.

Nothing, however, prevents us from designing a vehicle that a dog can handle. General Electric had a pass at this sort of thing some years ago when the company constructed an engine-powered vehicle with legs that walked instead of wheels that rolled. It was thought that such a device could operate well off the road. With it, a man could walk anywhere, carrying a big load. Again, though, the thing was designed strictly for use by human beings. One problem was that the human operator had too poor a "sense of touch." He couldn't feel his way along with his big metallic feet as he could with his own feet in contact with the surface. A highly skilled operator was required to devote his full attention to the device. The whole project just never seemed to get anywhere after construction of a great big demonstrator.

Consider this sort of design, though:

A small, likeable, happy dog might be placed in such a device while he is still very young, say, on the forty-ninth day of his life when he is ready for imprinting and can leave his mother without trauma.

Placed in this rig, the dog would learn rapidly how to move around without doing things he wasn't supposed to. Jumping up on people with engine power would be a no-no, for example. The dog would have to learn such fundamentals with firm training. However, he wouldn't have to be trained specifically to walk in Ole Dog-Mobile. He would learn very quickly to balance, run, turn, climb. The device would move just as he would.

A Chihuahua in the Dog-Mobile would never guess that his ability to move at 40 miles an hour and leap tall buildings in a single bound was abnormal. He and the Dog-Mobile would operate as one.

Human beings can handle trucks because trucks are designed for human beings to handle. A dog could handle the Dog-Mobile because the system is designed for dogs to handle.

The inhibition to development of this system is not technical but social. There is less moral objection to allowing human beings to bust their guts pulling plows than there is to letting dogs work cheerfully and effectively in Dog-Mobiles.

[ The continuing text below does not relate to the "Dog-Mobile", but is included for interest only. ]

Attempts to use animals in tasks reserved chiefly for human beings have met with serious objections in the past. One splendid story along these lines derives from World War Two.

A botanist, it is said, was puttering in his garden during the great conflict when it occurred to him that a lot of good, decent human beings were killing themselves in the attempt to deliver bombs to their targets. This kind of thing was common in those far-off days and it is not surprising that even a botanist should brood about the problem.

He thought it should be possible to train a small animal like a cat to guide an expendable aircraft-with-bomb to a target without risking a human life. This kamikaze-cat idea preyed on his mind until he got an opportunity to present it to the Army Air Corps, hoping that they would stir some cat expert to try it out.

The Army liked the idea and appointed him to try it out, ignoring his protests that he was but a simple plant fancier. They gave him a budget and a place to work and an order to train a cat to fly a bomb to a target. He knew nothing of cats.

He went to see some people who did know about the problems of training not just cats but people. The psychologists whose help he sought advised him to go about his task scientifically, limiting the number of variables as much as possible. They suggested that he stick with reliable, purebred cats whose backgrounds and performance probabilities were well known, and that he try not to upset them.

So, he got some classy cats. His first problem, then, was to try to get the attention of the classy cats. His efforts were useless. While the cats were moderately sociable, in the manner of all cats, they had no interest in his silly projects. In particular, they had no interest in being harnessed. He struggled to develop an escape-proof harness for cats and the cats developed many ingenious escape techniques. No matter what he tried, the cats were inclined to get upset and thwart his every effort scratching him unmercifully.

At last, his patience cracked and he disposed of his classy cats entirely. Instead, he went out in the area and found a miscellaneous cat rummaging in some trash cans. Following a brief disagreement over sovereignty and an additional set of severe scratches, he shoved the captive cat into a box without worrying about damage to the cat's psyche.

The box had certain special characteristics. For example, there was a copper screen across its floor, connected to an electrical switch. A touch of the switch would put some voltage through that screen and shock the cat. In addition, there was a small hole in the side of the box through which the cat could look.

The botanist equipped himself with a flashlight and began to move slowly about the laboratory. From time to time he would flash his light at the hole in the side of the box. If he saw no cat's eye looking through that hole at him, he touched the switch and gave the cat something to think about. If he saw the eye, he switched the flashlight off again and went about his business.

He discovered shortly that there was no position from which he could shine the flashlight through that hole without seeing the eye of the cat. There was no flash too brief to produce an instant response of eye-to-hole. Wherever he went in that laboratory, the eye followed him. In short, he had the cat's attention.

He next provided the cat with an interesting task.

He hung a stick on a swivel in the front of the cat's box with one end of the stick inside the box and the other end outside. By moving the end inside, the cat could control the position of the other end outside.

On the outside end of the stick, the botanist placed a small, flat board, so the stick was a bit like a hoe with a broad, flat end.

The botanist drew a curved line on the surface of the table where the box sat matching the arc along which the hoe-end of the stick could move. He let the cat watch all of this.

Then, he placed on the tabletop a wind-up mouse and let it run toward the box from which the cat was watching. When the mouse crossed the curved line, he pressed the switch that gave the cat something extra to think about. He did this several times, then reached into the box from above and held the cat 's paws to the stick. This time, when the mouse headed for the curved line, he moved the hoe-end of the stick so that the mouse was stopped as it reached the curved line. A few times he let the mouse get past that line and when it did, he zapped the cat. Soon, the cat was manipulating the stick himself to keep the mouse from crossing that line. Keeping himself carefully in a loose harness, with his eye held to the viewing hole, the cat saw to it that the mouse never crossed that curved line . . . and that no light ever flashed into the hole without striking a cat's eyeball. The botanist was relieved, if the cat was not.

The botanist summoned the Army Air Corps management. He showed them the can and the box and the mouse and the stick and the flashlight and the hole. He made all of these things work. He then explained that the next step seemed comparatively simple to him. It could safely be left to other trainers while he returned to his plants. What was wanted was a set of cross hairs and a picture of a target. He felt that the cat could transfer his experience with the mouse to the notion that if the cross hairs got off the center of that target he would be zapped. The cat's experience with the stick might be transferred to the control stick of an airplane, with an automatic pilot doing the rest of the chores. Trained to one picture, the attentive cat should be able to point the airplane at the real target and dive into it. One would have to catch another cat and start over, of course, but cats were more nearly expendable than pilots.

To the botanist's surprise, the Army Air Corps management was shocked and revolted by the demonstration—nauseated, even. They sent him back to his garden, dismantled his project and forbade its discussion. Pilots died instead of cats . . . or maybe it wouldn't have worked. Who cares, eh?*2

Do people worry a lot about the psyches of wallabies, compared to dogs? A Wallaby-Mobile might transport materials in jumps worth seeing.

And if we worry too much about animals to employ their intelligence instead of their strength, then what about Man, after all? No need to put him in a monster machine that's difficult to operate. How about designing a beast of burden that uses a man's own reflexes and low-level skills to carry a burden? Let this pack animal, this ass, be secured to the walking man himself in such a way as to dog his footsteps.

legs of the prosthetic ass would march right along with the man, engine powered, moving at his pace and with his own gait. The legs would be controlled by the movement of the man's legs but not necessarily in step with him. Probably their timing would be adjustable, controlled either automatically, by sensors, or by the man himself, so that the whole centaur like structure would not oscillate rhythmically and upset itself.

Climbing uneven paths and hills, the man might wish to take over more thoughtful control of the prosthetic ass, guiding its pace and steps to maximum useful effect. The hind legs might even help shove him up the hill. Indeed, there is no compelling reason to keep the ass behind all the time. It might be easier for the man to guide the thing in difficult terrain if it walked in front of him.

The appendage, sort of a prosthetic ass, would have its own set of walking legs over which the greater part of the pack burden would be placed so that the man himself carries very little. The one good thing about giving our kids machines to play with is that machine toys, unlike slaves, carry no particular ethical message that subverts the existing system. The machines are neutral. If we made the machines smarter, responsive to the wishes of the children—no, anticipatory of the wishes of the children, for machines, like tricycles and toy dogs, already respond to efforts at control by the child—then this neutrality might vanish, or seem to.

Already we see very young Indian children at places like Santo Domingo School in New Mexico, responding to the patient, friendly, and respectful attention of a timesharing computer. Indian kids who have avoided school like the plague now run, not walk, to the computer room to work diligently at tasks presented by the machine. The problem is to make the computer seem smarter and smarter so that it can continue to challenge students who have learned its tricks of randomly simulated intelligence and grow bored with it. The computer is not intelligent, of course. It doesn't even have Natural Wisdom. It does only what clever human beings have programmed it to do . . . at least this is the story. At times, however, it becomes difficult to distinguish computer performance from human performance. Occasionally we are caught off guard by our own cleverness in constructing systems that simulate human activity.

Some of us who are not really ancient can remember when schoolteachers confidently explained to us that Man is different from other animals in a number of significant respects. For example, only man uses tools. Only Man speaks. Only Man laughs.

In the last fifteen years we have discovered that various animals use tools. For example, chimps ordinarily use sticks to reach objects beyond their hand's reach or to pick up ants from a hole in an anthill for a light snack.

"Ah, but that's just tool using," say the experts. The tools are not specialized, made for a particular purpose. The chimp just picks up whatever is at hand.

Then we see chimps stripping extra twigs and bark off branches to make good reaching sticks. "Yes, but . . ." say the experts.

Then we see chimps making effective little dippers out of leaves to get at water in the hollows of trees.

"Yes . . . but . ."

Then we see the porpoises laughing at us after a good joke.

"Yes . . . but . . . but . . ."

Then we learn that chimps can in fact talk with human beings in sign language, developing vocabularies of useful size, using words generally, assembling new sentences out of words to meet new situations.

"But . . . but . . . but . ."

We have been retreating from our firm attitudes on machine intelligence in much the same way. When a computer does something that only human beings have been able to do heretofore, we declare that something "unintelligent."

"But that's just ordinary arithmetic logic, something that machines can be programmed to do, nothing creative." Yet computers are being used as self-organizing systems to do tasks that have previously been defined as "creative." We cannot settle these questions here and won't try. Human beings seem better able to respond "appropriately" to changing inputs than anything else that exists in nature. Still, the differences between Man's intelligence and the intelligence of other things seem increasingly to be differences of degree, rather than of kind.

Oddly, people seem not to welcome intelligent company in this difficult universe but to shun it. Smart animals scare us and the prospect of smart machines terrifies us. Perhaps this is a survival characteristic and we should be glad to recognize it in ourselves.

But perhaps not.

*1 The man/machine interface in the case of the reindeer and the Lapplander's sleigh is a ring through the reindeer's nose. Ouch.

*2 Another experiment in this era evoked less moral objection but fell afoul of the management because it worked so well. Somebody noticed that bats tend to hang in belfries and under eaves and rooftops as morning approaches. He reasoned that bats might be equipped with tiny incendiary time bombs. If such bats were released from airplanes over a Japanese city, the bats would carry the bombs to the most vulnerable places in the city and would efficiently burn the whole place down when the bombs went off.

Evidently nobody had any great empathy with bats. A test was set up in which several hundred bomb-laden bats were released just after dark by a bomber flying over a model Japanese city that had been constructed in the Mojave Desert. The incendiaries were set to go off at dawn, just as the bats settled in and before anybody could get a good look at them. Sure enough, just at dawn the model city burst into satisfactory flames … and so did the air base ten miles away where about half the bats had flown from their release point.

No bats, either, thank you. The possibilities are obvious.

Why do we insist on leaving our machinery stupid?

Update Apr 2012 – Nelson Winkless offers the following: "You might want to credit Carl Hawk for the drawings (at least, the good ones, not the ones I did), including that of the dog-operated vehicle. Carl was long a technical illustrator at Sandia Laboratories, the Atomic Bomb Works, here in Albuquerque, and as a retiree, was enjoying picking up some freelance work like this. Nice man. I don't know if he's still among us, but it would be a nice gesture to give him credit."

In 1956, the late Dr. Iben Browning (d. 1990) was selected to head a newly-formed independent Research Division at Bell Aircraft Corporation of Buffalo, New York. The first technical report [678] produced by the new Division, authored by Browning and published in December 1956, purported to present a “periodic table of the physical universe” – that is, a comprehensive classification scheme for research that encompassed studies of all material objects at all size scales. The table listed four different states of matter and the disciplines associated with them including: (1) the natural non-living state, (2) the natural living state, (3) the unnatural non-living state, and (4) the unnatural living state. Unfortunately, the fourth category was censored out of the report by Browning’s superiors at Bell Aircraft and did not see print until 1978, when the full report (with the deleted text restored) was reprinted by Winkless and Browning in their book Robots On Your Doorstep [679].

According to Winkless [679], writing about these events two decades later in 1978, the fourth category provided a discussion of “…robots that could reproduce. It seems not wholly implausible these days that machines might be constructed that could build other machines just like themselves. Given what we know about computers, we can even imagine that these machines might have artificially constructed and programmed reflexes and responses that would help them survive, avoid hazards in the real world, and seek the materials needed for construction of more of their kind. In 1956 this was more than Bell Aircraft Corporation could bear. The subject was just too far out, damaging to the reputation and practical effectiveness of the company. The robots were eliminated from the proceedings….” Dr. Browning left the company soon afterwards, perhaps discouraged when an assistant vice-president diverted a significant portion of the new Research Division budget to hire a psychic medium advisor for Bell Aircraft Corporation.

678. Iben Browning, “Organization and Vistas of the Entirety: A Periodic Table,” Report No. 98-001, Research Division, Bell Aircraft Corporation, December 1956. Reprinted in: Nelson B. Winkless III, Iben Browning, Robots on Your Doorstep: A Book About Thinking Machines, Robotics Press, Portland, 1978, pp. 13-36.

679. Nelson B. Winkless III, Iben Browning, Robots on Your Doorstep: A Book About Thinking Machines, Robotics Press, Portland, 1978.

Prosthetic-ass:

Inspired by the above article:

[pic here]