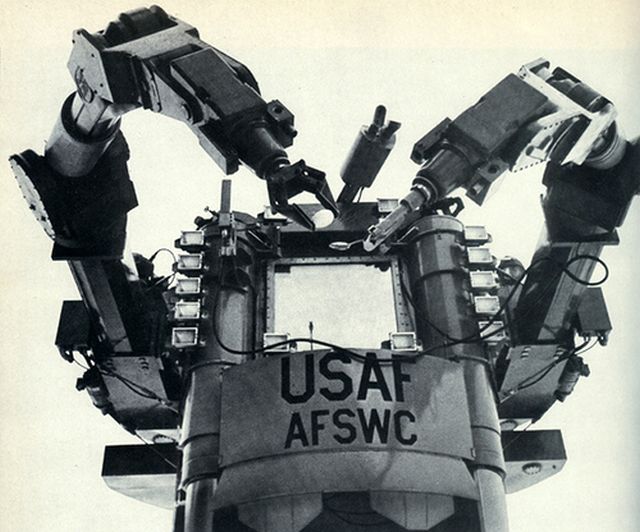

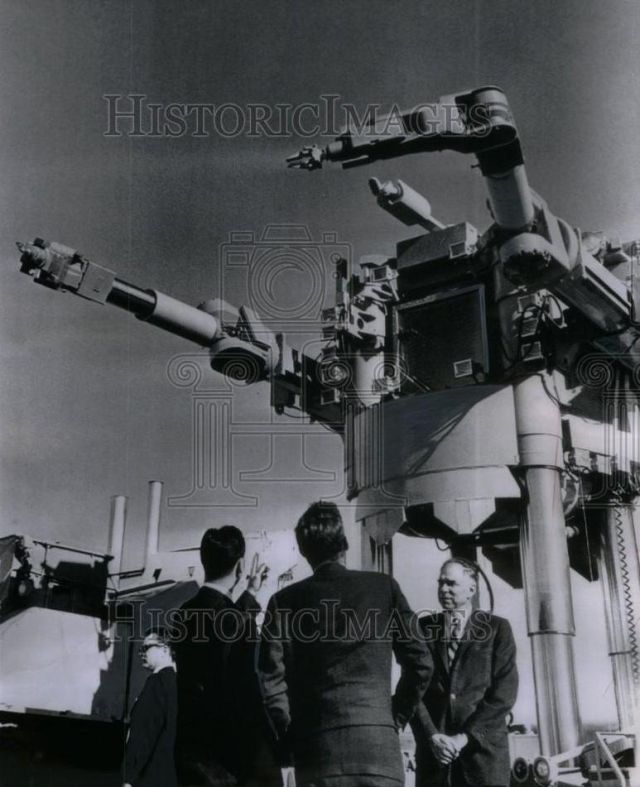

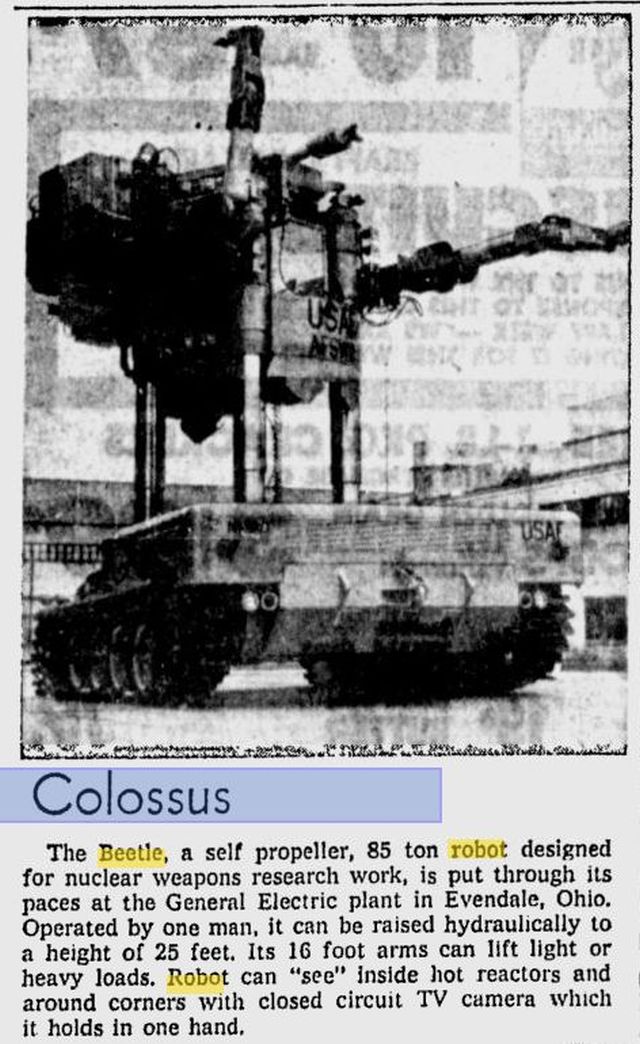

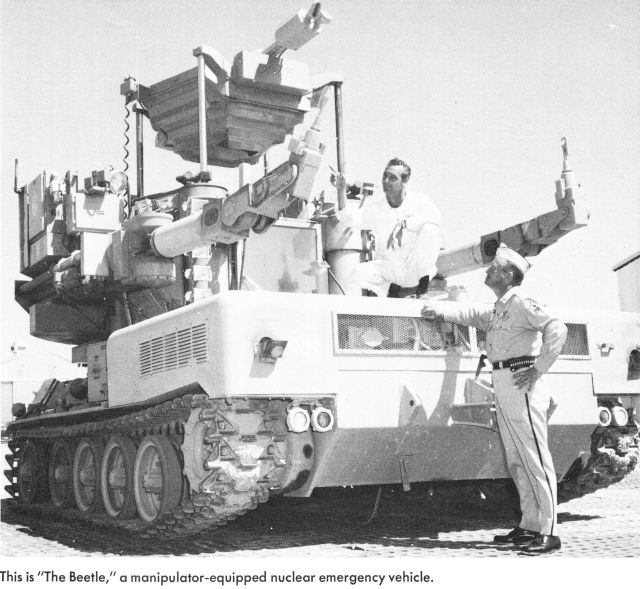

1958-62 – "Beetle" Mobile Manipulator.

Background Information:

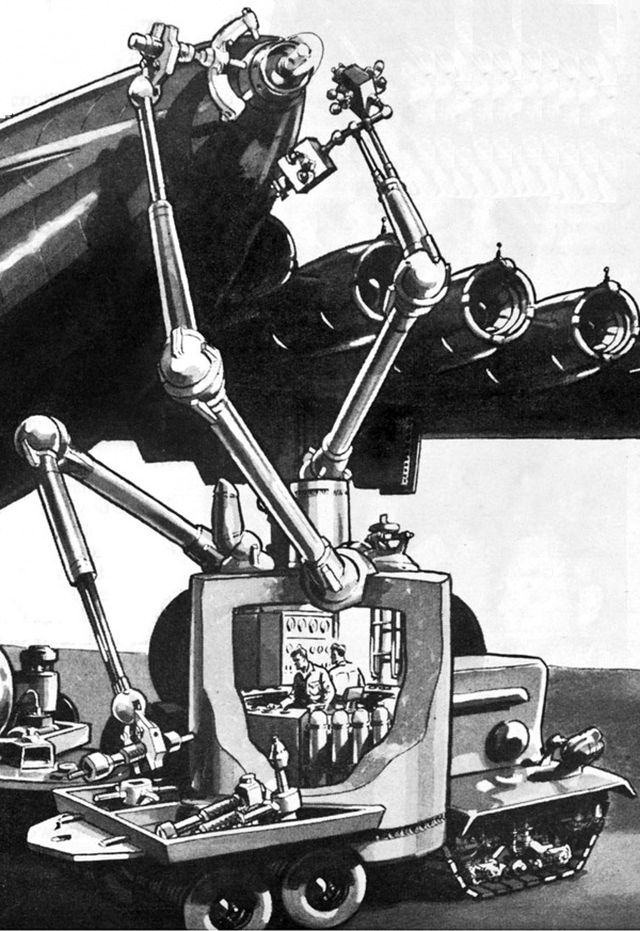

Popular Mechanic's (Sep 1956) drawing made by Frank Tinsley from designs by Lee A. Ohlinger of Northrop Aviation, Inc. of a robot mechanic for the proposed atomic-powered airplane, a star-crossed project that stumbled through 10 years and $500,000 without ever getting off the ground.

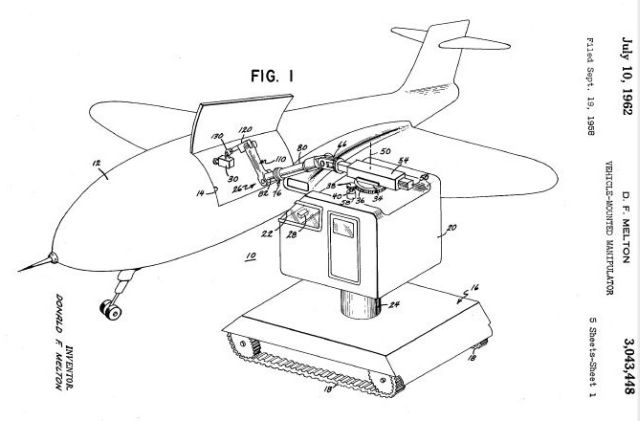

General Mills was one company that patented a 'Vehicle-Mounted Manipulator' in 1958 as its proposal for atomic-powered aircraft maintenance, amongst other purposes.

Publication number US3043448 A

Publication date Jul 10, 1962

Filing date Sep 19, 1958

Inventors Melton Donald F

Original Assignee Gen Mills Inc

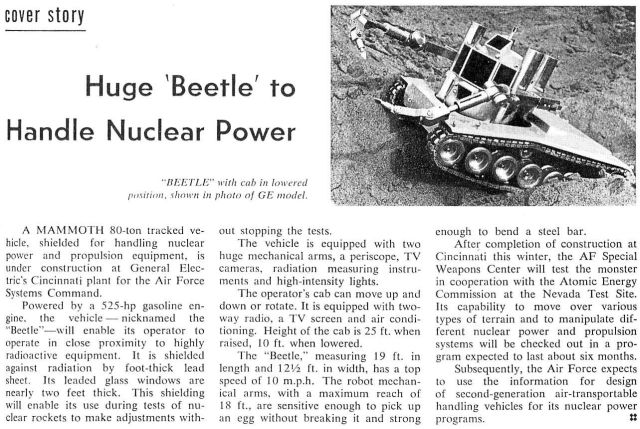

Source: Missiles and Rockets, Volume 9, 1961

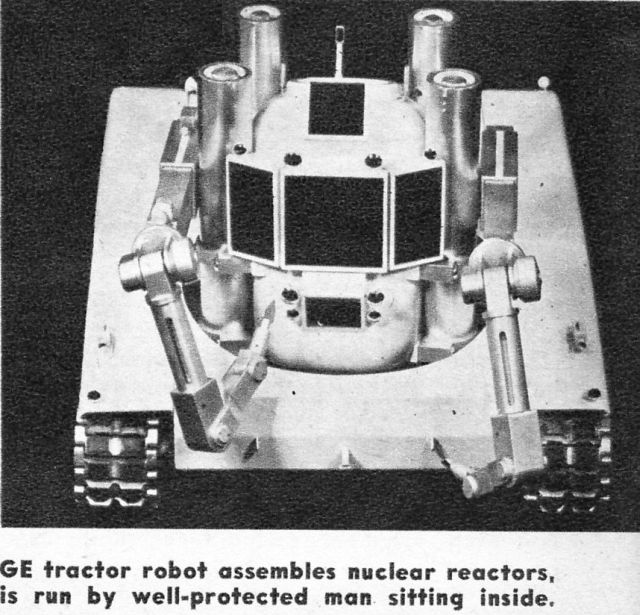

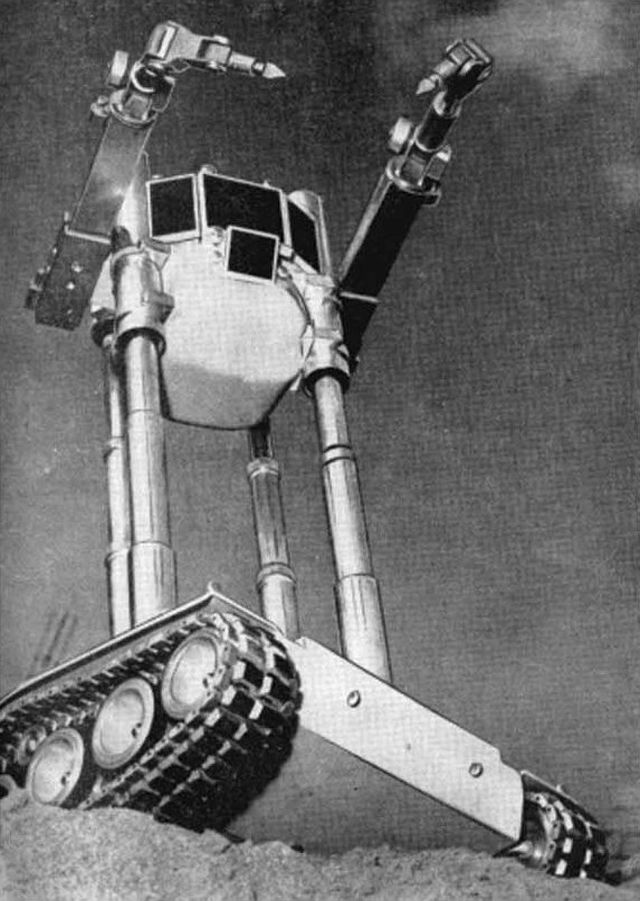

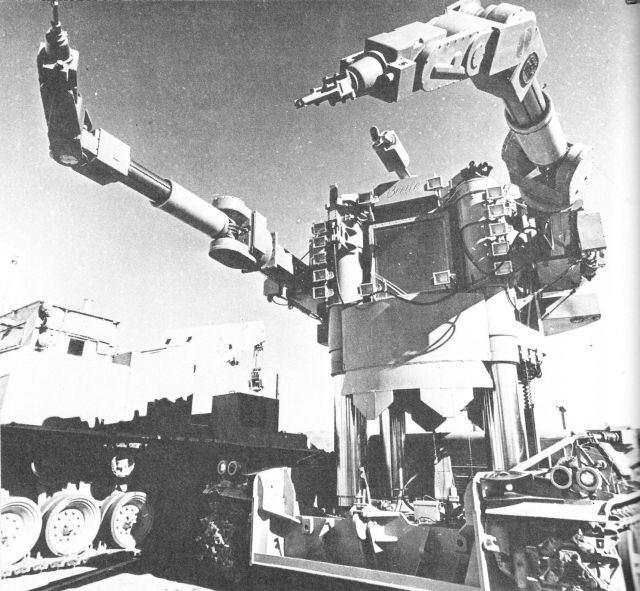

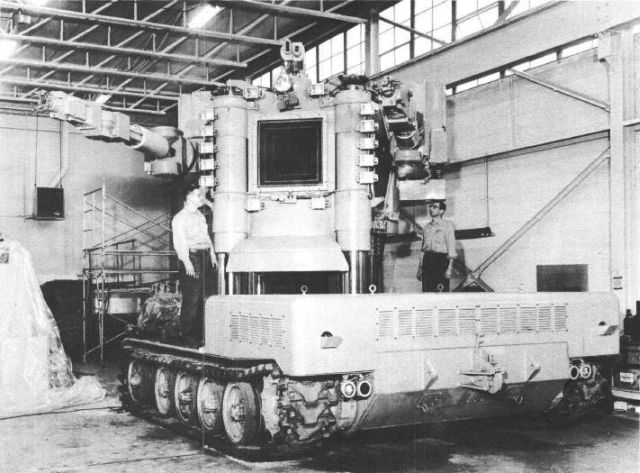

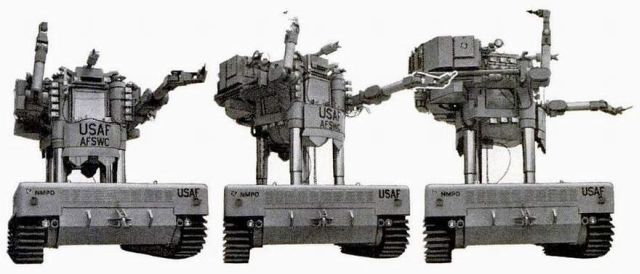

In 1961, GE's Beetle was under construction. The above few pictures show the model that was built beforehand.

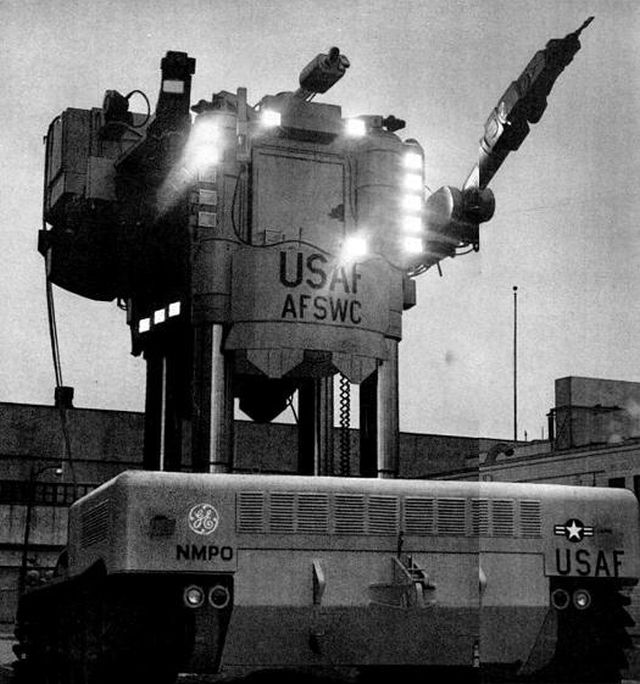

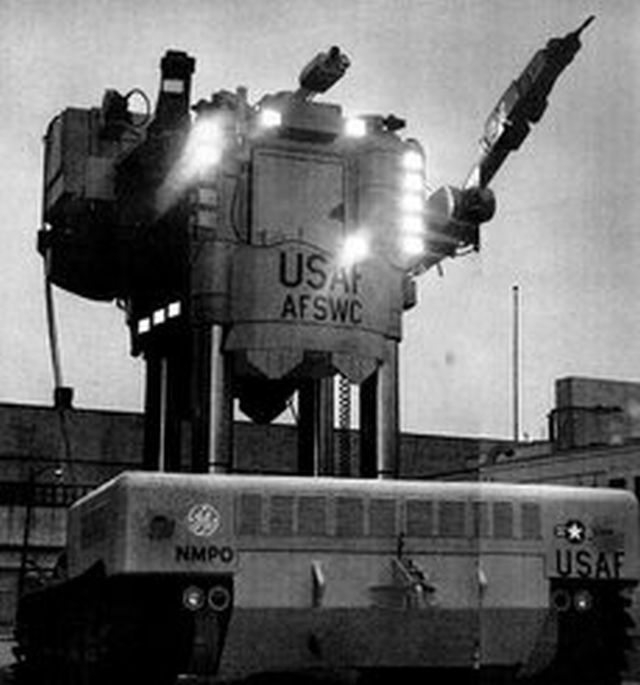

World's Biggest Robot By Martin Mann

Fix an atomic rocket engine? Clean up spills of radioactivity? Rescue H-bomb victims? That's what the Beetle is for

THAT monster glaring at you from the left is the biggest robot ever made. It weighs 170,000 pounds in its double-thick rubber treads. It can punch its claw hand through a concrete wall or gently stretch stainless-steel arms to pluck an egg off the top of a house.

There's a man inside. Safe within the lead-and-steel cab, he can work where no unarmored man could live -in the deadly radiation that atomic energy the most fearsome as well as the most promising invention of the century.

He could roll right up to the atomic engine of a space rocket and delicately maneuvering those 16-foot arms, make adjustments. Or he could replace a broken part in the atomic boiler of a power plant. Or haul the fatally hot debris of a nuclear accident away to the burying ground. If H-bombs struck he could dash into the destruction zone to rescue injured people and scrape away the worst of the fallout dust.

That's what this bizarre machine, named the Beetle, can do. When PS Chief Photographer Bill Morris and I first saw the Beetle, it wasn't doing anything but sitting on a hangar floor. They couldn't start the engine.

Beetle is first of a family of robots that will handle the hot jobs of the atomic age

Robot with a bellyache. In four days it operated seldom, and then it limped more than ran. There was difficulty with the degassing circuit. A plug popped and hydraulic fluid squirted out (a dedicated engineer, Dutch-boy-like, stuck his finger in the hole). A diode blew, immobilizing one arm (a welder had dropped a tool into the control chassis). The auxiliary generator pooped out (brush trouble). It seemed that short circuits had their own short circuits (after all, there are 400 miles of wiring in the thing).

Such bugs are standard equipment in any complex new machine. They were cleaned up in a furious week of round- the-clock troubleshooting. But these setbacks were only the culmination of troubles that dogged the Beetle from the beginning. It was originally designed to be a robot mechanic for the atomic-powered airplane, a star-crossed project that stumbled through 10 years and $500,000 without ever getting off the ground. So the Beetle is an orphan. The Air Force, which paid $1,500,000 for it, still isn't sure exactly what it will be used for. Yet the need for machines of this type is so certain that the orphan is already fathering a whole family of newer robots. The next models, now on the drafting boards, will bear only a family resemblance to Papa Beetle. They'll be smaller and lighter, so they can be air-lifted where needed. Most will be remote-controlled–without a man inside you don't need all that heavy radiation shielding.

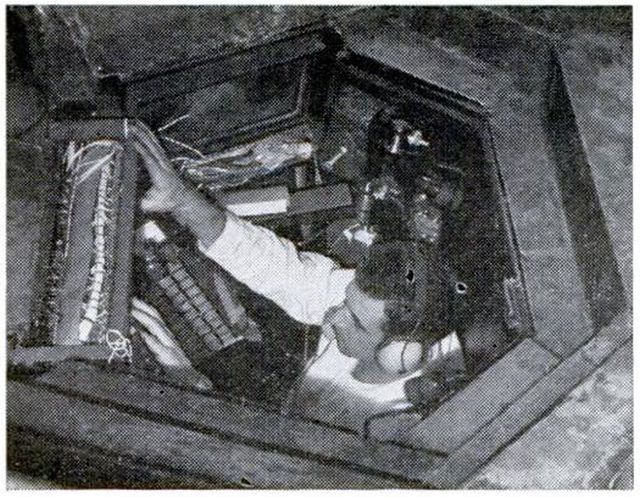

The Beetle does carry a man. That makes it more versatile. But it also requires some of the most elaborate engineering ever lavished on any ground vehicle.

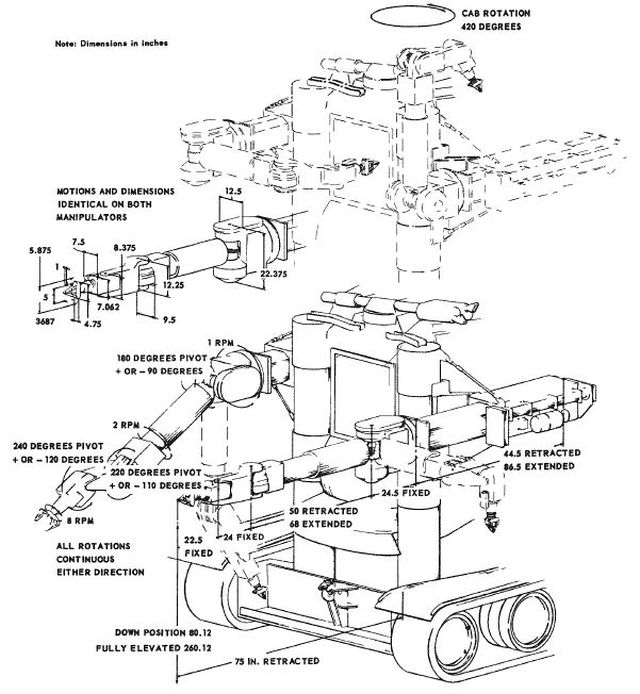

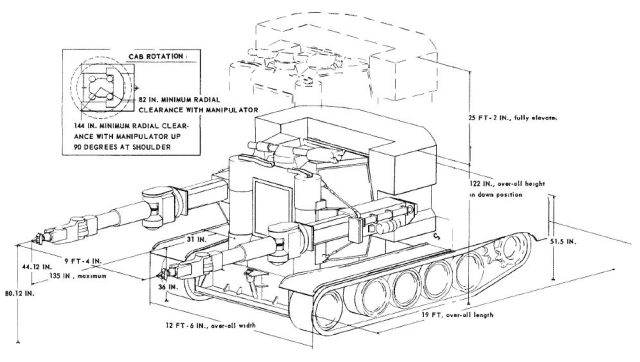

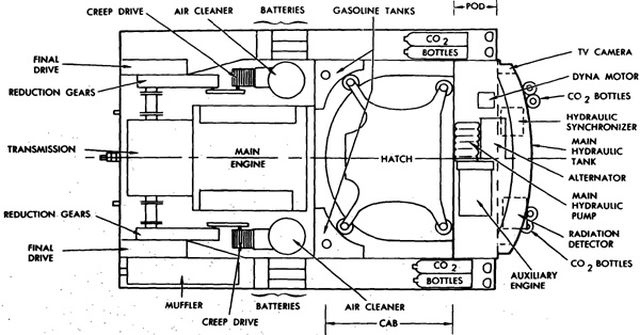

It looks like a tank because the chassis is reworked from an Army M42 40-mm. gun carrier. A 500-hp supercharged Continental six speeds it along roads at 10 m.p.h., but there's also an electrical drive by which it creeps 15 feet per minute. It could wrench the concrete all off a test cell without grunting hard–drawbar pull is 85,000 pounds.

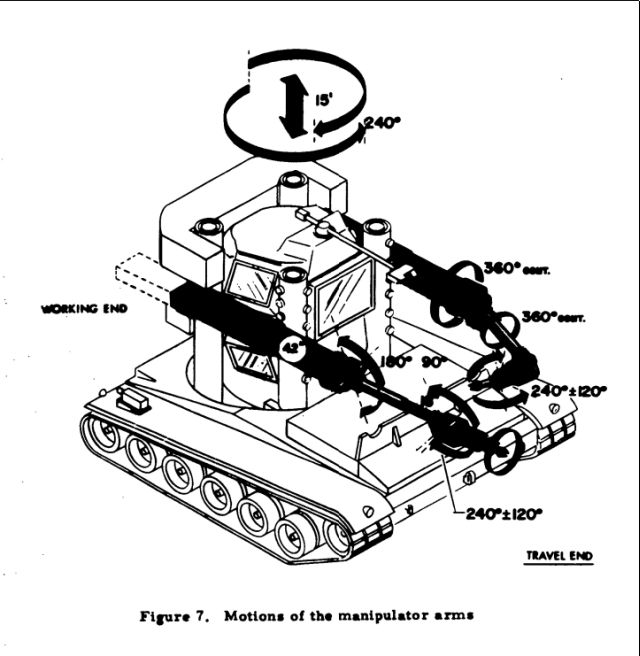

The cab, however, is nothing like a tank turret. It not only turns around and around, but moves up and down 15 feet on four stainless-steel legs (built like hydraulic auto lifts). These movements are precise but slow, for that cab weighs 50 tons.

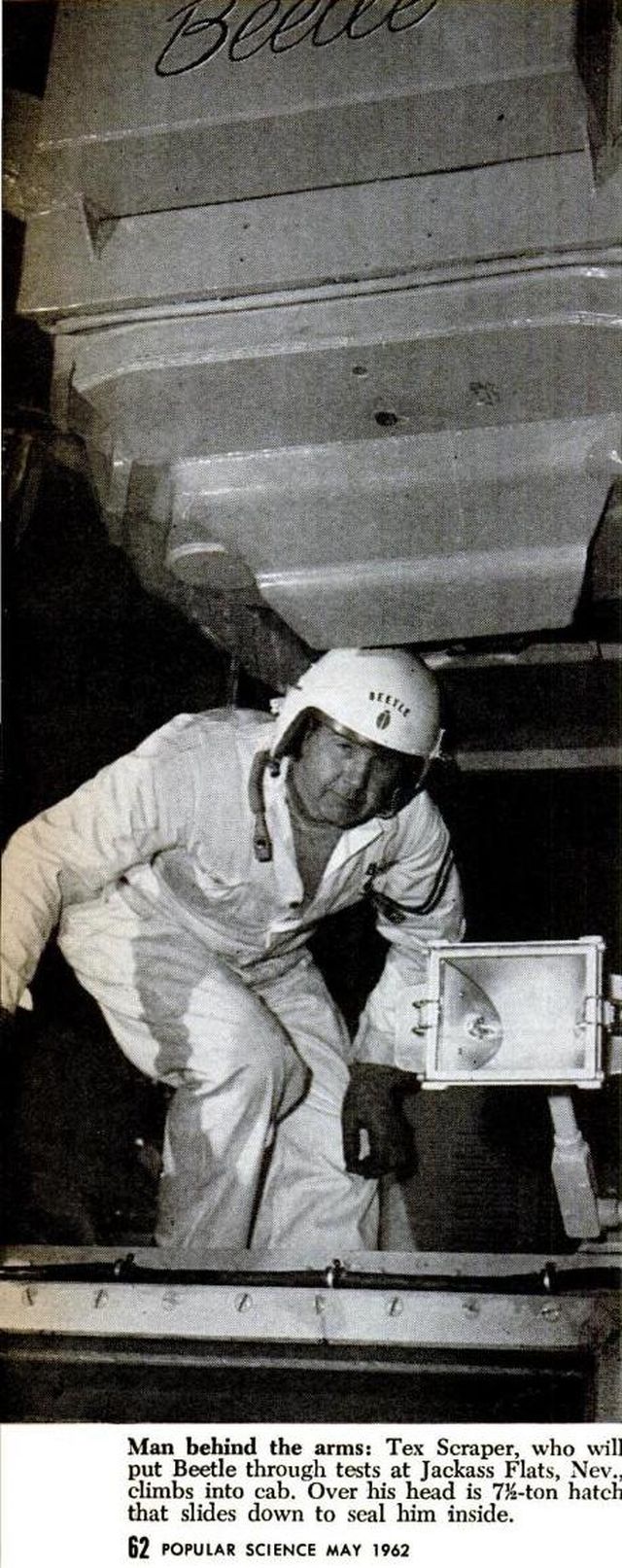

The walls are made of foot-thick lead covered inside and out with half inch steel plates. The entrance hatch is a tight-fitting cork of lead directly over the operator's head. It alone weighs 7 1/2 tons.

The hatch offers the only way in or out.

Understandably, there are four separate mechanisms for raising it: the regular hydraulic system, the battery-powered hydraulic pump, a hand pump on the operator's left armrest, and hand pump outside the cab.

Even with the four independent emergency outs, the operators seat is still no place for a guy with claustrophobia. It's eerily oppressive even when the hatch is wide open (I tried it). Those 50 tons of lead and steel form the most effective suit of armor ever wrapped around a single man. It cuts down atomic rays by 3,000 times. That means the operator could put in a full day's work where the radiation level was 3,000 roentgens per hour. Unshielded exposure to such intense radiation would probably kill him after 10 minutes.

The man who will seal himself inside this massive machine is young, flamboyant Randall Scraper, who comes from Indiana, but is always called Tex. Scrapper is one of the most skilful of an elite corps of technicians, the professional manipulators.

These specialists perform the same work as any repairman–taking machines apart and putting them back together again. But there is one big difference: The manipulators work on machines too "hot" to get close to. They cannot touch their work or even their tools. Everything must be done at long range with mechanical arms.

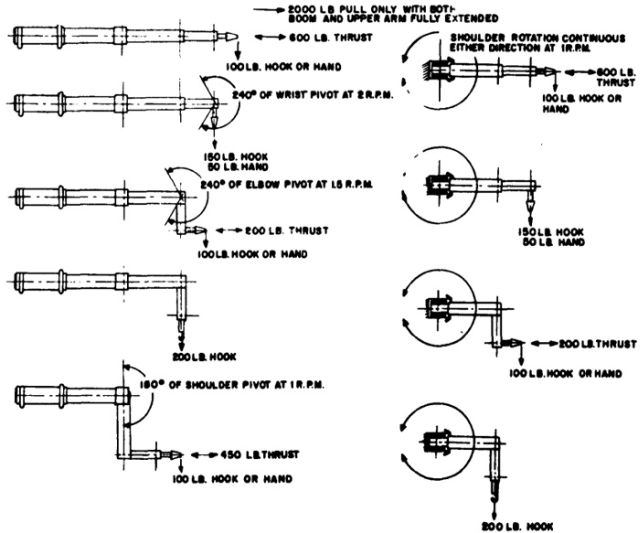

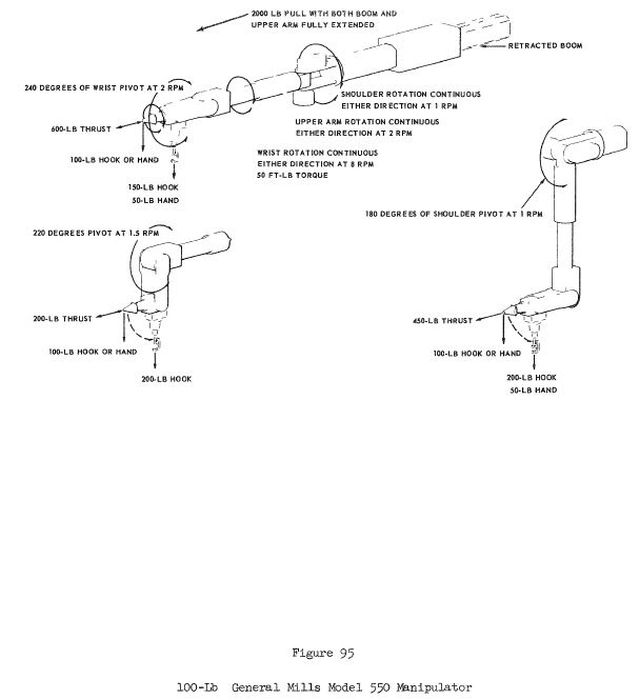

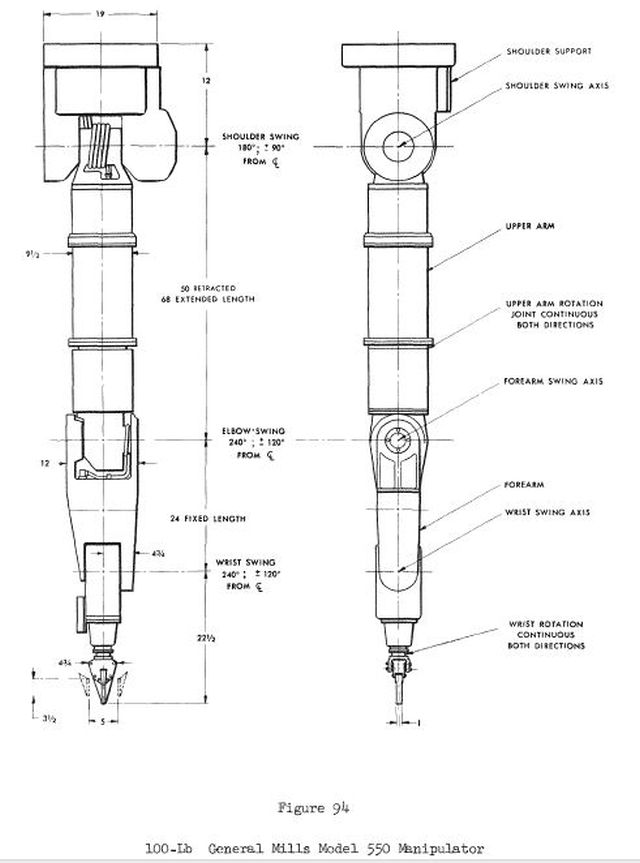

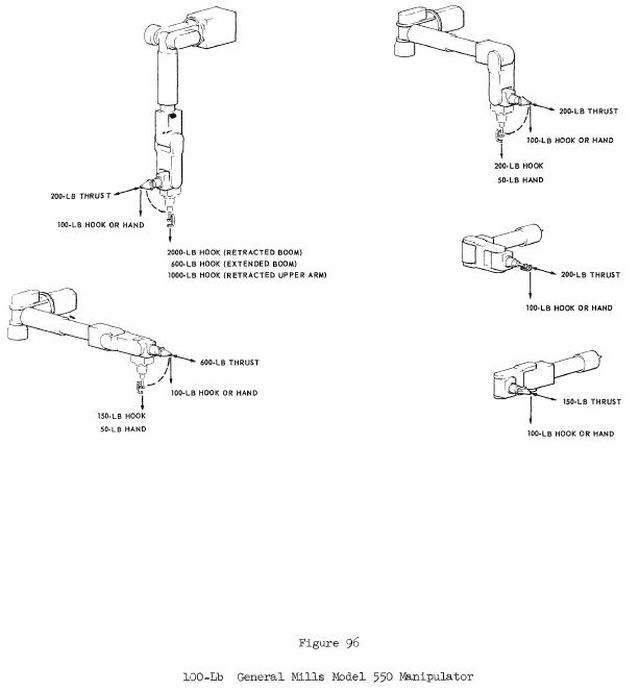

No sense-no feeling. The arm is a stainless-steel boned, electrically muscled copy of human equipment: shoulder, upper arm, elbow, forearm, wrist, and hand. The joints are superhuman: They spin around and around as well as bend. The hand is usually a two-fingered claw that can grasp and manoeuver parts or tools: but it can be snapped off and replaced by any of any specialized types–a socket-tipped finger, for instance.

The steel hand cannot feel, however, and that is a serious loss.You can't tell whether you are crushing something or holding it too loosley it will fall. (Dropping a nut or screw seldom matters: spilling a can of radioactive material could tie things up for weeks.)

Working with mechanical arrms is like playing the nickel-in-the-slot claw machine at an amusement park–and snaring the toy compass every time. It takes unusually sensitive coordination as well as icily calm concentrating–outwardly at least. Tex Scraper steadily chews gum and cigars, often both at once. But he possesses the supreme patience to devote eight hours to removing one nut from a bolt.

"I can do that,: Scraper drawls. "because I turn my ears off. People are always watching, trying to help. 'A little to the right,' they tell me. Well, it may be their right and my left. So I've taught myself to pay no mind. I don't even hear them."

The Beetle is worth its cost solely to take Scraper and his mechanical arms up close to the hot nuts and bolts. He gets safety and a clear view of the work (not perfect, yet better than television). But he pays for these advantages with total isolation.

The operator is sealed tight a mummy. There is barely space to wiggle a foot; standing or stretching is out of the question. His only direct connection to the outside world is an air intake.

(The duct zigzags, like the entrance to a photographic darkroom so that radiation cannot "shine" in. Special filters are unnecessary because the air itself does not become radioactive.)

A three-ton air conditioner keeps Scraper cosy (72 to 76 degrees, 60-percent humidity) even if the temperature outside plummets to 25 below or flames to 130 above zero. He talks to base by radio (two separate transmitter-receivers) or public-address system.

There's even a microphone out front so that he can listen to the engine.

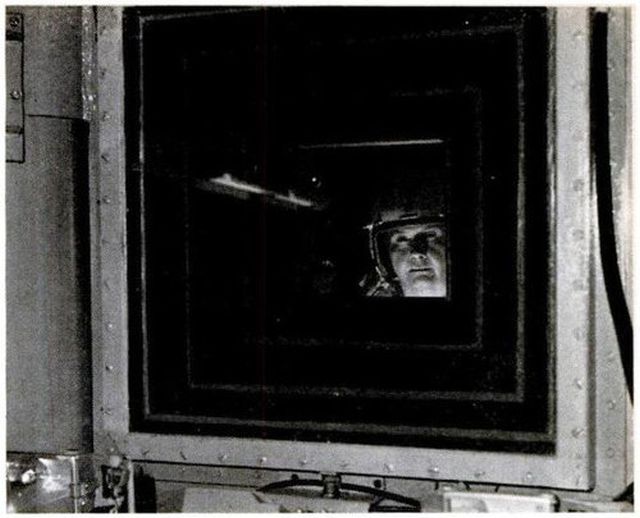

A room with a view. Even more elaborate are the arrangements for looking out.

To go with the windows, there are two pairs of binoculars on swinging mounts; with them Scraper can read the scale of a standard micrometer gauging parts many feet distance.

There is a retracting, submarine-style periscope that rotates and tilts.

Finally there is closed-circuit TV. The screen sits between his legs. One camera is clipped to the cab, like a pencil in a man's breast pocket. It can be picked up and moved around by the mechanical arms. Two fixed cameras point to the rear so that Scraper can see what's going on behind him–outside rear-view mirrors are impractical.

The Beetle's cab even includes a few luxury accessories: a comfortable, power adjusted chair, ash tray, lighter. Most important of all, perhaps, is an oxygen bottle. If absolutely everything went wrong, it could sustain Scraper for eight hours. Presumably that would give time to haul the machine out of danger, cut the cab open, and free him.

Source: Popular Science, May 1962.

Built by Jered Industries in Detroit for General Electric's Nuclear Materials and Propulsion Operation division, the Beetle was designed for the Air Force Special Weapons Centre, initially to service and maintain a planned fleet of atomic-powered Air Force bombers. According to declassified Air Force reports, work began on the 'Beetle' in 1959, and it was completed in 1961.

It has also been said [Halacy, "The Robots Are Here!", 1965] that the Beetle was built for NASA's "Project Rover", a nuclear rocket development program.

Life Magazine, 4 May 1962 had a brief article and a couple of pictures of the Beetle.

Beetle showing its versitility by putting an egg on a spoon. Not bad given the size and types of grippers, and lack of tactile feedback to the operator.

A startled look as the Beetle is spotted in the make-up mirror.

President Kennedy (back to camera) having a look.

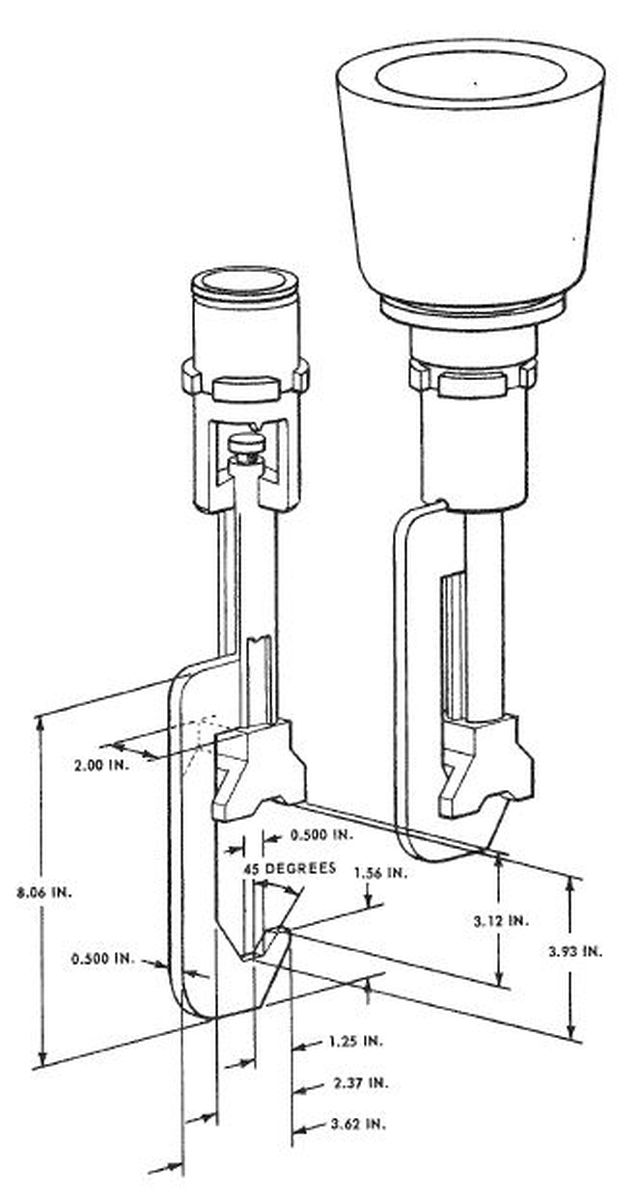

The Beetles' Arms and Hands

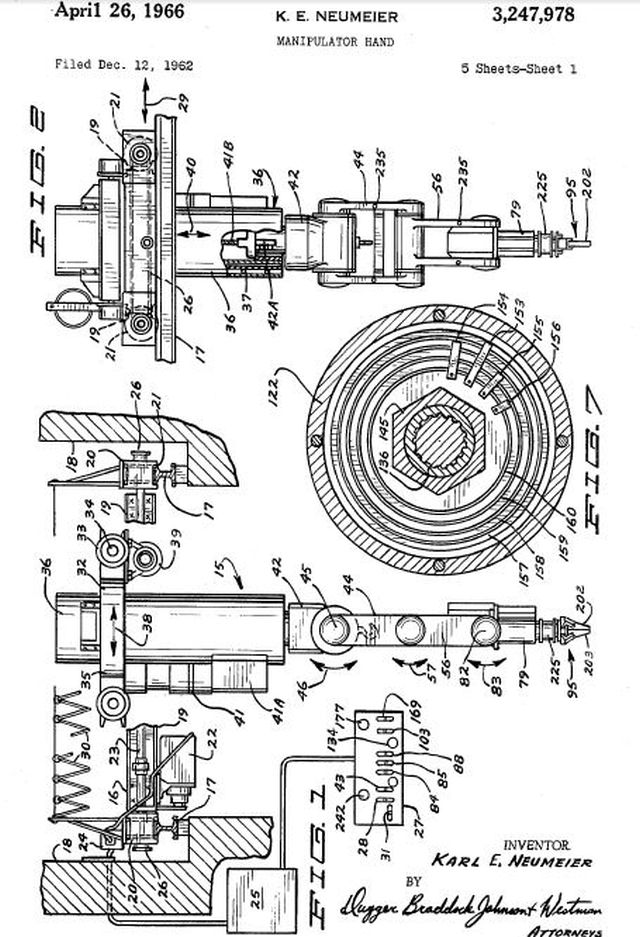

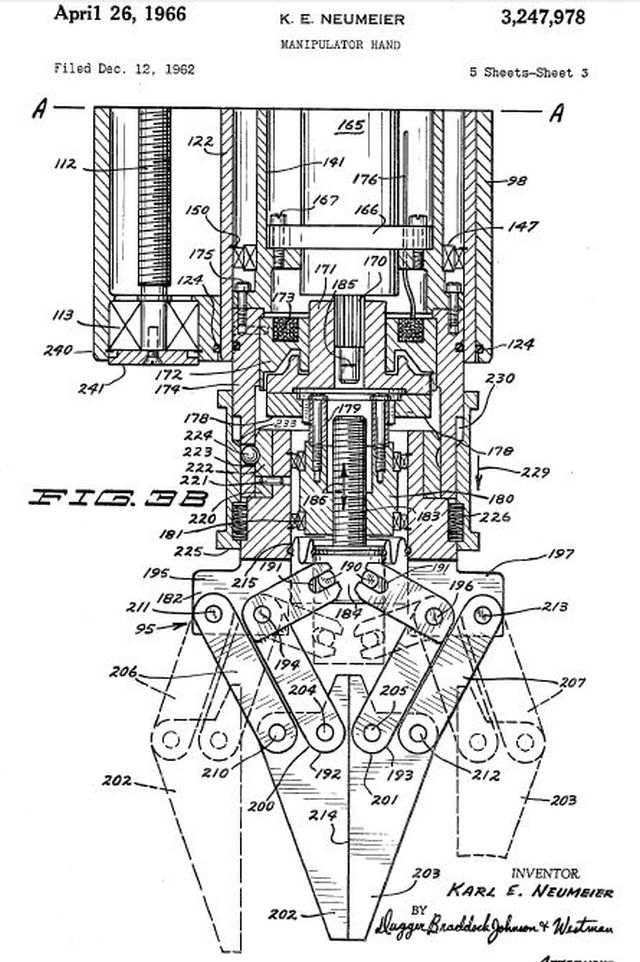

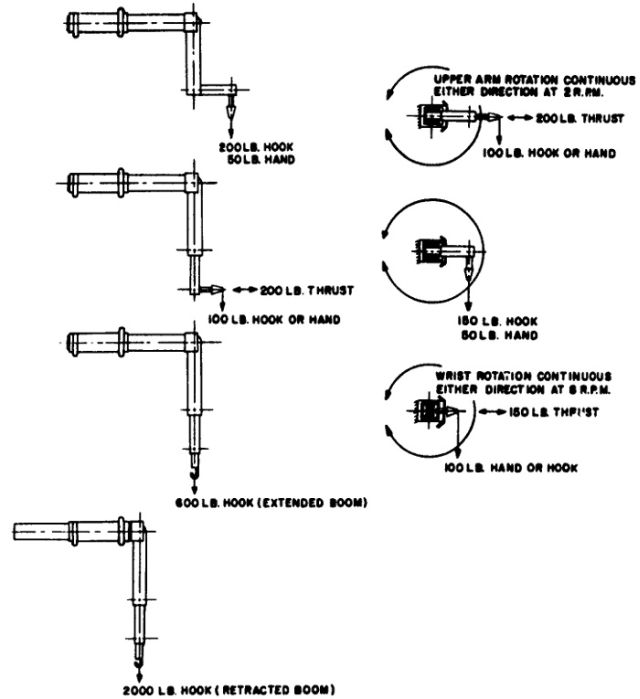

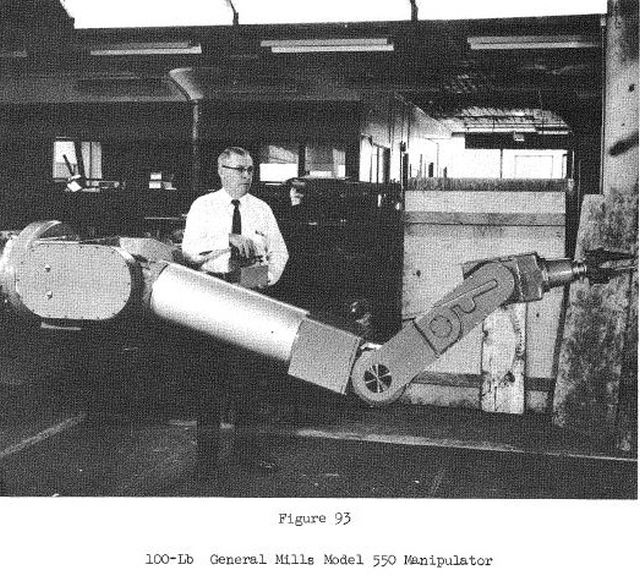

The General Mills arm used in the Beetle is very similar to this arm descibed by patent US3247978. Karl Neumeier was one of General Mills engineers.

The two-fingered hand is also described in the patent and is most likely the same if not very similar to that used on the Beetle's manipulator arms.

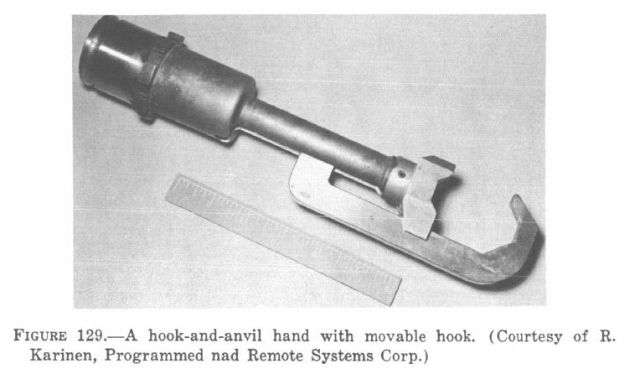

General Mills Hook-and-anvil hand. {Image says PaR Systems, which was a spin-off from General Mills]

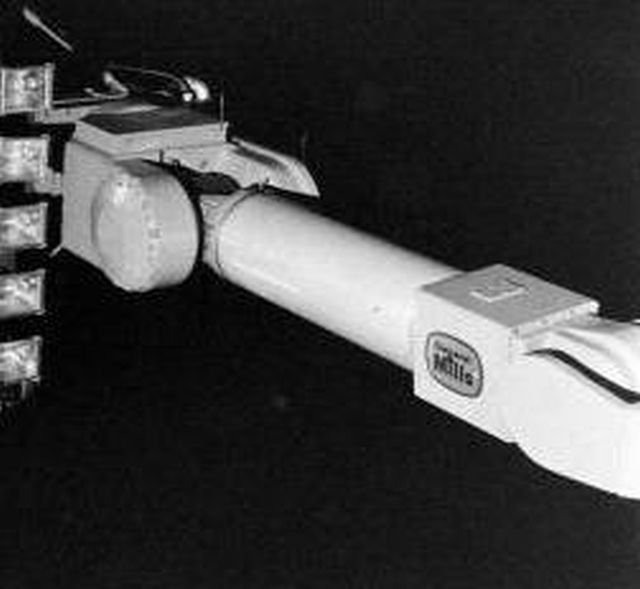

The General Mills logo on the manipulator arm.

In the Life Magazine article mentioned above, Getty-LIFE have a lot of images from that photo shoot. They appear in the photo gallery below.

Invalid Displayed Gallery

See other early Teleoperators and Industrial Robots here.