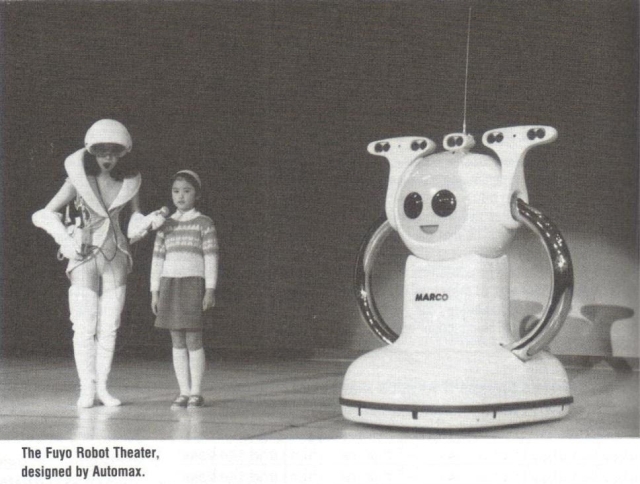

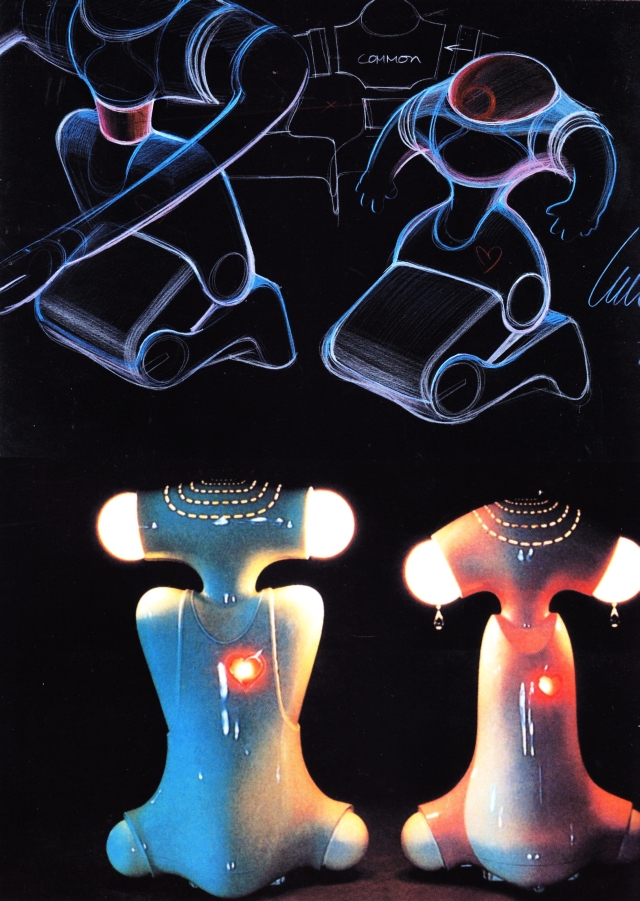

Perhaps the most impressive robot show [from Expo'85] is at the Fuyo Robot Theater. In this exhibit hall, whose exterior is shaped like a pearl in an opening oyster, the robots basically have the run of the place, entertaining visitors with a complicated floor show. Through voice recognition and voice synthesis, visitors can actually communicate with the dozens of robots roaming through the hall. Fuyo claims that the robots here enjoy "a high degree of independence and social life," and while that may be true, one wonders if the robots care.

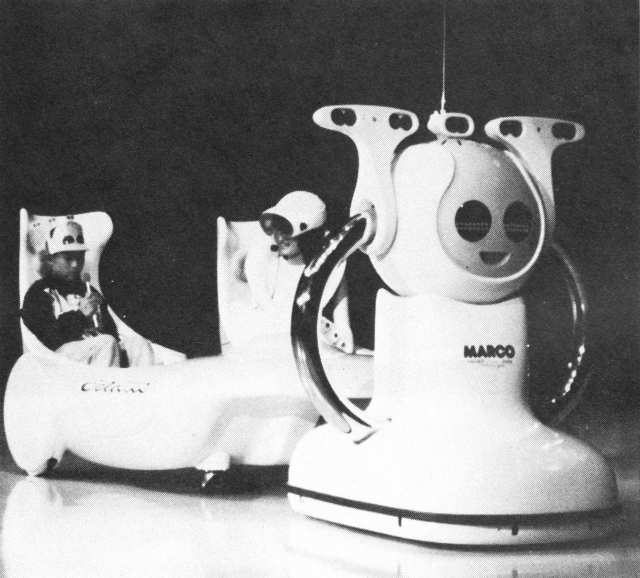

Note the Colani signature on the carts – see partial interview with Colani below.

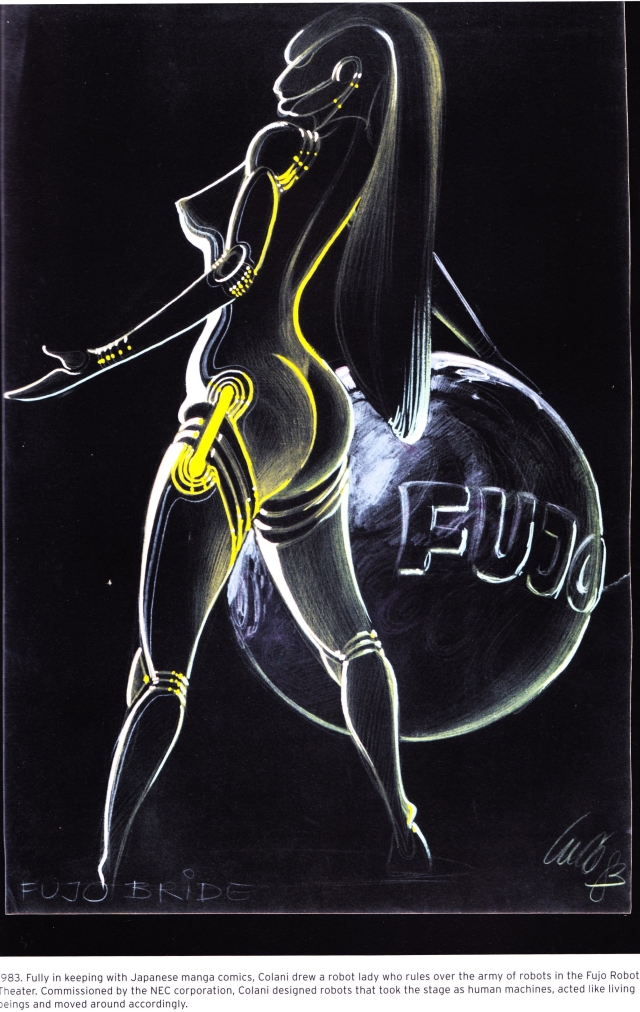

FUYO ROBOT THEATER

“Tomorrow's Science For the Enrichment of Mankind”

Robots are machines created by science and technology, but they can still become man's friends. The aim is to demonstrate how advanced science and technology becomes, it must always be to the benefit and enrichment of mankind. The Fuyo Robot Theater will make you think about this by introducing you to some jolly robots.

Seen from across B Block, the Fuyo pavilion featured a lively show featuring robot performers that interacted with each other. Moving about on wheels, they interacted with each other through lights and sounds, all set to a fast paced musical score.

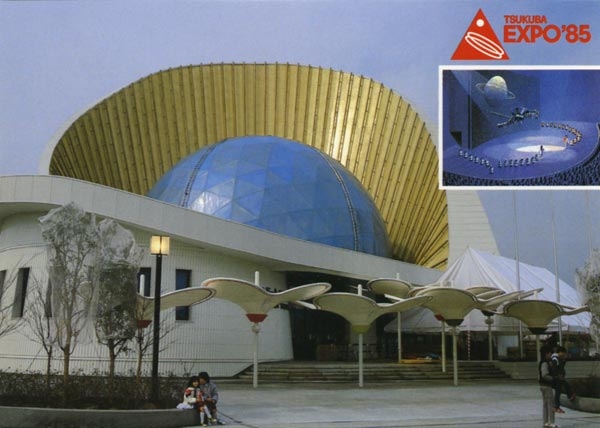

The Fuyo Robot Theater is housed in a stunning pearl-in-the-shell structure.

Luigi Colani designed the Fuyo Robot Theater, and Shulshl Kanno (pictured) produced it. Note the small blue Colani-designed "Baby Robot" in the foreground.

I've been amazed over the years by Luigi Colani's futuristic biodesigns. Until building this post I hadn't realised his involvement in the Expo'85 Fuyo Robot Theater. Here is some further information of the Colani involvement:

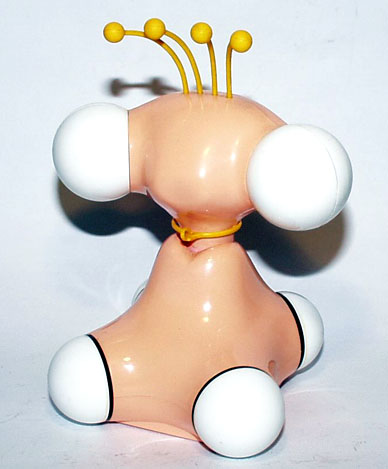

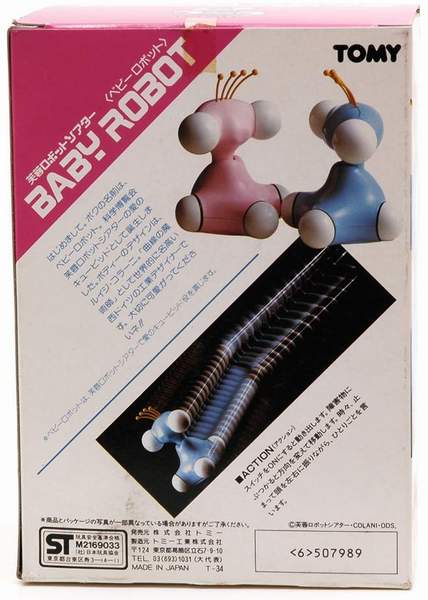

The "Baby Robot"designed by Colani.

ANOTHER CLOUD BREAKING NEO IMPULSE HAS TO COME

An extract of a conversation between Colani and Albrecht Bangert on Japan and the relationship of technology and nature. See full interview here.

BANGERT: Did Japan influence Colani or Colani influence Japan?

COLANI: European artists such as Toulouse Lautrec, van Gogh, Vallotton or Americans Frank Lloyd Wright and McNeill Whistler were fascinated and stimulated by Japanese culture. Their vision and oeuvre was strongly influenced by Japanese art. By the same token there were also many Japanese artists who were profoundly influenced by European modernity – by Le Corbusier and some Cubist painters to name but a few.

This cultural exchange has been going on since Japan opened its doors to the outside world in the middle of the 19th century and

I am proud that I was able to contribute to this process of mutual influence with my Biodesign. The connection between myself and Japan is thus of a very special nature. The invention of biodesign in the broadest and traditional sense in Japan derived from the roots of Shintoism and the Japanese notion of "kimochi", that is to say a sensibility for the atmospheric. Western culture considers ratio to be the nucleus of all human activity. By contrast in the Far East, the belief is that nothing endures unless created through kimochi as the manifestation of the universal energy or ki in our own psyches. For only this marriage of the emotional and the world of things will create something lasting that is likewise in line with our spirit. Apparently I seem to have had a not insignificant influence on the radical and deep-rooting revival of these ideas in Japan – particularly when it comes to biodesign combined with the most modern technology and production methods. The connection between my design philosophy and Japan is thus very close, in both practical and in-tellectual terms.

On the one hand, I was deeply influenced by Japan through its people, its culture and its design. On the other, I was able to in-spire many Japanese young people with a European style biodesign. The idea of an organic biodesign was enthusiastically received in Japan. Influenced by their own roots in Shinto religion and the Japanese “kimochi“, the atmospheric, an amalgam developed from the Colani-minded fund which continues to have an affect in Japan today and which in my case too, has remained the main vein of my activity.

Asian people whom I met in those days were fascinated by a mixture of high tech and emotion. This remains a precarious balancing act for all major designers constantly balance. We have to work emotionally on integrating technology, and this is just as strongly required as it was in those days. Japan has understood this better than the rest of the world, that it is about more than just pure technology, but about a feeling for technology. Sometimes more technology and less form is crucial while at other times, more form and less technology is required.

————-

BANGERT: Back in the 1970s you already sketched robots and showed in YLEM how deep-sea robots set up and maintained algae cultures. In the 1980s, you also drew robots in Japan. What is the relationship between man and robot?

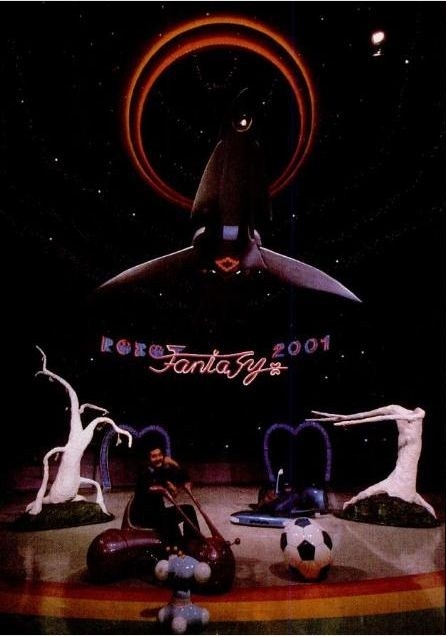

COLANI: That is very easy and concise to explain. At the time I received the assignment from the Fuyo Group to develop a robot theater, robots were rationalizing jobs away in Japan. And there was a first wave of animosity towards the robot. And then I was asked, “Colani, make the robot friendly. Bring the robot back into play as a companion and not as a foe who takes away jobs!” And I received a contract and the great opportunity of making a two-hour robot theater wihtout any people. There was a single woman who played around with it but there were many more dozen robots which were built and which were the big sensation at the Tzukuba Expo ‘85. They immediately improved the image of the robot in Japan, also a wave of imitations was launched with the cute smallest robots which were also shown in this play – from little Tamagochis to the ear-wagging Sony dogs – and today we have a wave of copies. The friendly robot image is a Colani invention from the Tsukuba Expo ‘85 where we won the first and second prize.

BANGERT: I believe that you created your greatest affinity to Japan with the robots because they look like Japanese comic figures and they really match the Japanese mentality and their love of such cute things. How is it that you were able to create such a range of Japan-like figures with so much fantasy?

COLANI: My task was to make robots cute. And this succeeded in a perfect form against the backdrop of my profound observations of Japanese design, old Japanese graphics, and the Japanese tri-vializing of forms which can be found in all aspects of life in Japan. In the ‘nezukes‘ you have these wonderful, almost sculptural brilliant depictions made with scant means, and these robots are made so succinct with extreme economy of form.

The task I was given by the large group I worked for was something really astonishing: We wanted a queue of people in front of our theater which no one could overlook. A queue which was so long that we could justifiably claim we had made the robot socially acceptable again. And this was absolutely successful. Such masses of people as those who stood before our Fuyo Robot Theater, could not be seen anywhere else in the whole Tsukuba exhibition.

BANGERT: Today, robots are once again the big attraction in Japan. The entire World Expo in Aichi appears to live from a revival of these robots. How do you think robots should be designed today?

COLANI: Today, of course, you can see signs of abrasion and wear in the robot world. The robot once again has become overly technoid in Japan and this is a mild mistake. It has to be high-tech of course but the design side is somewhat lagging behind.

And we are right now on the point of showing the Japanese again with our Baby Robot which is supposed to learn to walk, which has fallen on its nose 75 times and on the 76th try stands up quietly, attempts a first step, falls again, and then takes a second and a third, that we have to start from the very basics again. We have to go the whole way and take a profound look at the external design of robots to rid the robot of its aggression. After all, the robot takes away from us, from humans, large areas of life. From craftsmen, too. And like in the Art Nouveau period when the applied arts, sculptors and designers revolted against mass industrialization, today we have to create a Neo Art Nouveau again, we have to work on making machines much closer to nature so that we can bring Yin-Yang into computers and into robots. Once again we are too far removed from the nature-like image of the robot.

This is something we have to work on again and I would like to introduce new stimulus again about which we will have to speak at our exhibition.

—-

April 6, 2005