The name "Kaiser" comes from the title of a video clip found at British Pathe here. Its actual name is not known at this time.

WORKING MODEL OF THE KAISER

Captain Alban J. Roberts – mobile, light-operated automaton 1920's (responsible for robots attributed to Jasper Maskelyne (music halls) and occasionally incorrectly attributed to Capt W. H. Richards (Eric the Robot) in error due to similar names. Errantly, we also see the name Alan Roberts pop up as well.

I'm going to make a few claims about Capt. Alban J. Roberts and his automatons.

From my research, "Kaiser" is the first:

- electrically powered automaton suited in sheet metal ie a tin man.

- electrically powered automaton to offer a walking / skating action without the need for an external prop ie a cart.

- electrically powered automaton (in human form) to be remote controlled, in this case by light.

- electrically powered automaton (in human form) to be semi-autonomous ie self-contained (no external power or control wires), but not self-controlled.

By these claims, Robert's "Kaiser" pre-dates the previous holder of some of these "firsts" – namely Capt. Richards' "Eric" of 1928, which appeared around the same time as the humaniform of Wensley's "Televox". I'll go a step further and even suggest that "Kaiser" may have even influenced Fritz Lang's visualisation of "Futura" in his production of "Metropolis" which commenced in 1925.

Although born in New Zealand, the technology behind Roberts' automatons was evolving and being used by him in New Zealand, Australia, even USA and India. However, the first occurrance I can find of the existence of his automatons is in London, U.K.

Biography of Alban J. Roberts:

1880 – Alban Joseph Roberts -Born in Wellington, New Zealand 28/8/1880

Registration Number 1880/12836

Family Name Roberts

Given Name(s) Alban Joseph

Mother's Given Name(s) Kate Clara

Father's Given Name(s) William Henry1904 – Running Municipal Electric Lighting Works – Patea, N.Z. Resigned June 1904.

1905 – Christchurch – Patented Meat marker.Instructor in Electricity at Kaiapoi Technical Classes.

1908 – Early experiments in wireless in 1908 in Sydney, Australia.

1909 – registered new member for Aero Club of the UK ("Flight" magazine)

1910 – Wireless motor-launch at Dagenham Lake, Essex, England with F. Heeley

Hippodrome demonstration with wireless dirigible [same year as Raymond Phillips]. Torpedo demonstration.1913 – Demonstration of Wireless Dirigible back in New Zealand.

1914 – AJR on his way to London via Australia – Demonstrates Wireless dirigible. Stays due to war outbreak.

1914 – 1918 – World War I

1915 – Flight Apr 16, 1915 mentions "wireless Dirigible" at the Hippodrome, London. operator is Mr Raymond Phillips, not Roberts. [see earlier date of 1910 for Phillips].

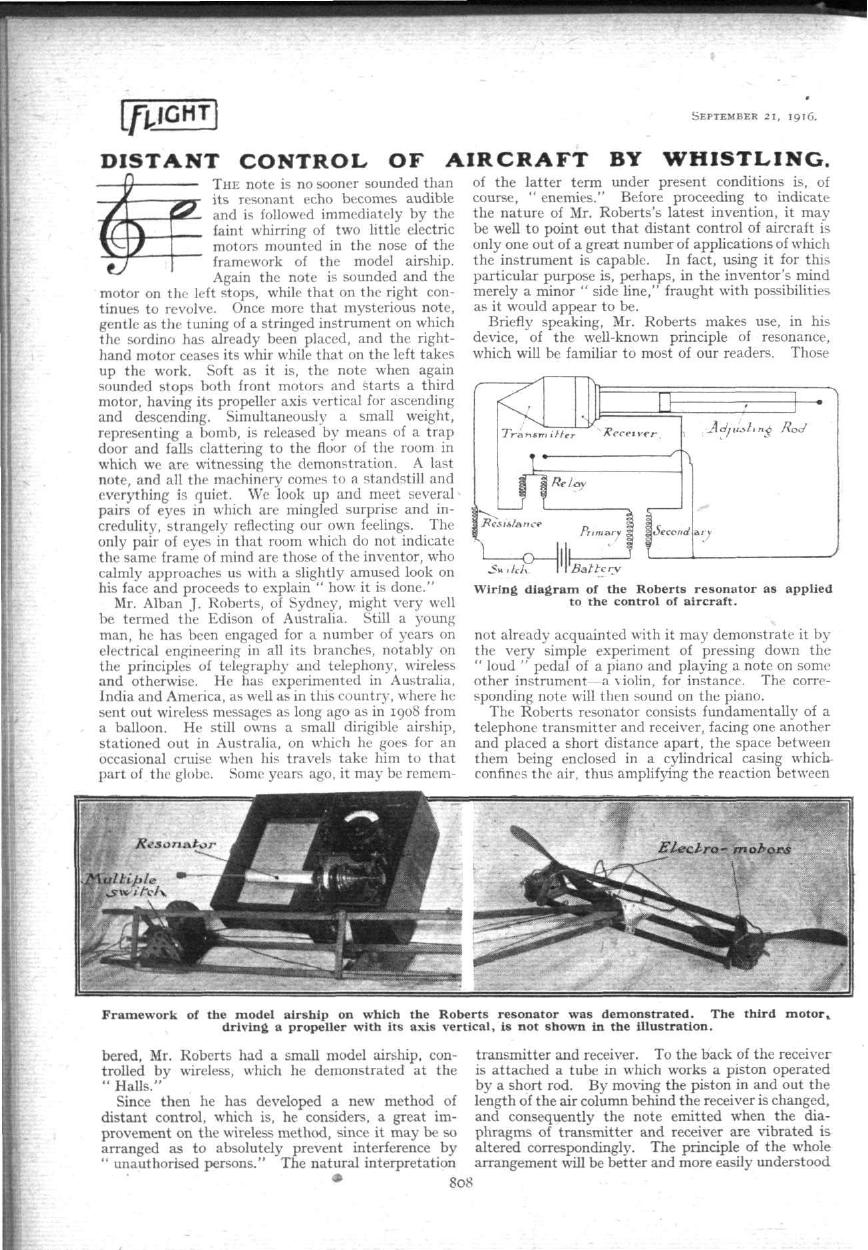

1916 – "Flight" Sept 21 1916 – "distant control of aircraft by whistling" -reprinted in (Scientific American Supplement, No. 2155, April 21, 1917, p. 245.)

Mentions he experimented in Australia, India, America, and the UK.1918 WWI – Alban Joseph Roberts. RNAS Officers Service (Royal Naval Air Service)

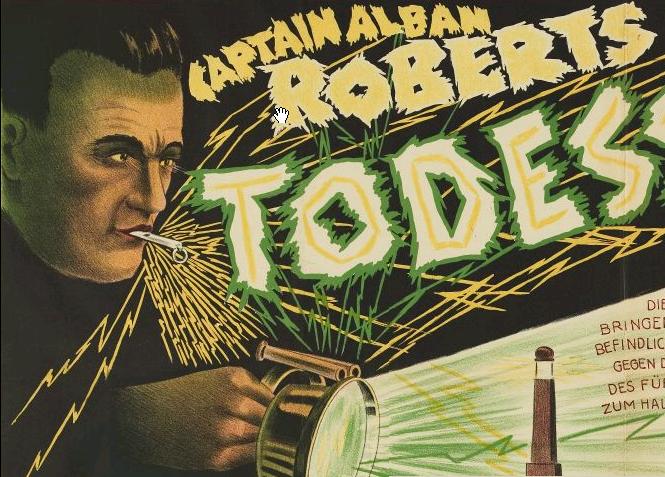

1920 – Automaton walks by sound control – reported in London "Era" and Australian "Argus" . Newsreel also reports 12 Feb 1920 as the date for "Kaiser" the robot.

1921 – (1 August to 13 September) – St George's Hall appearance.

1921 – Capt Alban J. Roberts performed for Maskelyne at St George's Hall. Mentions "Life-Size Automaton Controlled by Light Vibration."

1923 – (2nd to 14th July) Capt Alban J. Roberts performed at St George's Hall for Maskelyne (according to "The Times" advertisements).

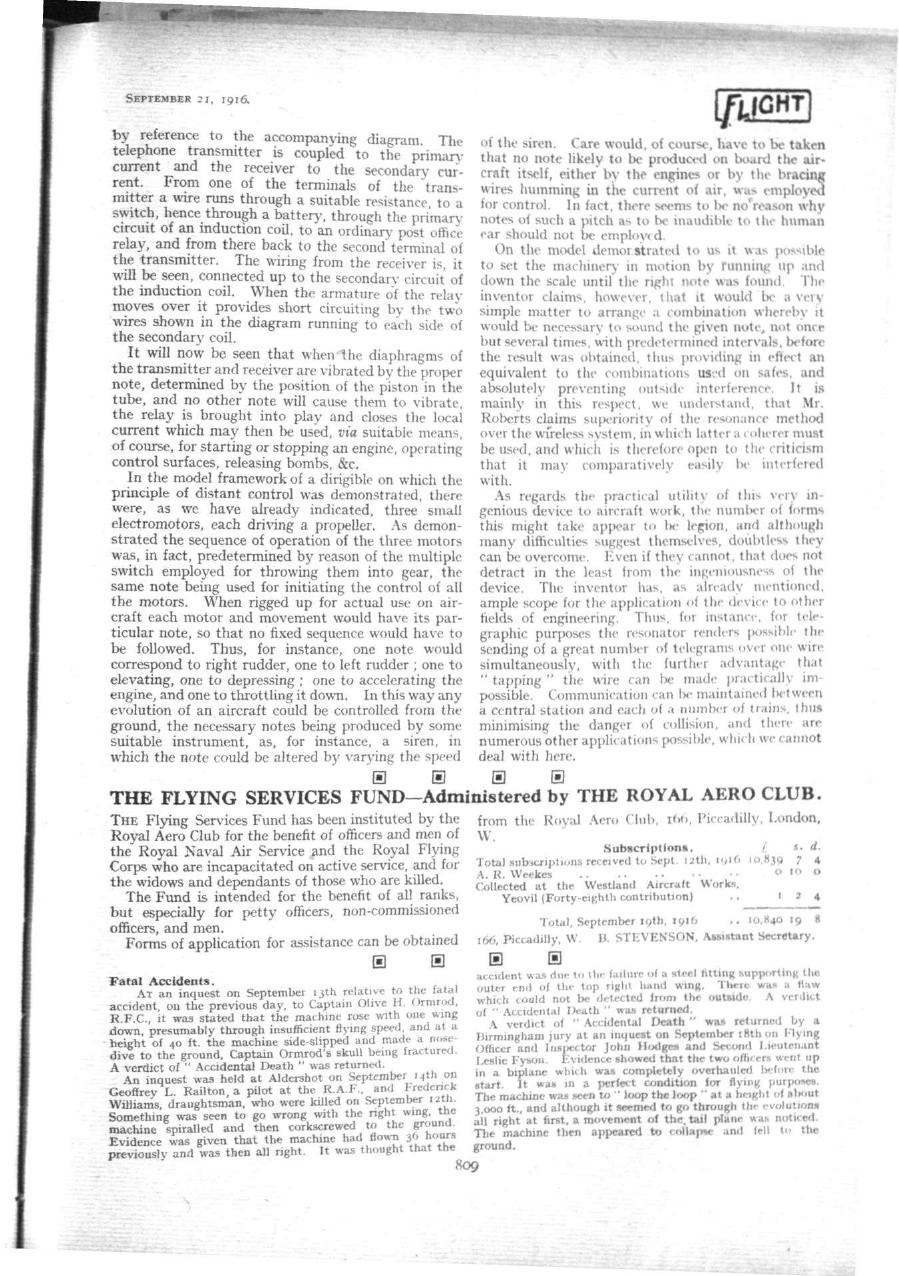

1924 – Dutch / German Circus poster (Circus Busch) showing female automaton on skates.

1925 – "Argus" Newspaper – Aerial Torpedo 12 Aug 1925

1928 – (10 September) Roberts returns to St George's Hall for a five week engagement with "The Robot". Most published press available is of this event. Robot looks like a sheik – maybe "Lawrence of Arabia". Probably booked by Noel Maskelyne.

1930 – Roberts patents advertising device – UK 1,769,311

1938 – Director of Visular Directions Ltd, a new company in London (Flight Mag)

1950 – Died in England, U.K. aged 70.

The Argus (Melbourne, Vic. , Australia Saturday 22 May 1920 Page10

"No more amazing turn has been seen even at the Coliseum than that labelled "Vibrations Harnessed" (writes the London "Era"). Captain Alban J. Roberts, a New Zealand inventor, has apparently learned how to subdue light and found to his will, by a brilliant ray of light he causes balloons to explode and bells to ring, and by sound he makes an automaton walk and a miniature motor-car move at his direction. The scientists may be able to understand this harnessing of light and sound, but we frankly admit that to us it partook of the miraculous."

The Technology Behind Alban J. Roberts' Automatons.

Although I have another post describing the underlying technologies behind early automatons and robots (see here), I will highlight those deployed and even invented by Roberts.

The automaton is not mentioned in the below article from Popular Science, April 1929. Examples of light control and sound control are shown. notice also the mis-spelling of "Alban".

from Flight Magazine

Flight Sept 21 1916

"Distant control of aircraft by whistling"

reprinted in Aircraft.—Distant control of aircraft by whistling. Diagram of device. (Scientific American Supplement, No. 2155, April 21, 1917, p. 245.)

Some posters from a Dutch site on early European Circus (see here)

.jpg)

Alban J. Roberts – "Kaiser" photo gallery – (stills from video clip)

See Robert's later Mechanical Man here.

Addendum

Death Rays

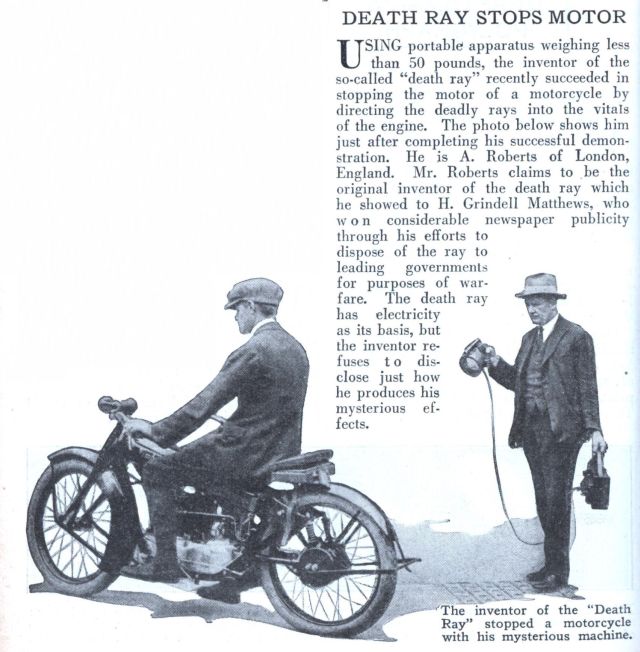

A.J. Roberts involved with Motorcycle 'death ray' experiment.

The Harry Grindell Matthews story is quite amazing. see here Grindell 'Death Ray' Matthews . It appears Matthews 'stole' Robert's ideas and tried to make money from them himself. The "Death Ray" was most likely a focused light then when being shone onto a selenium cell, triggered some function, such as turning the power off or operating a relay to break a circuit. It was a trick.

Interesting also that Matthews probably stole Roberts idea re aerial advertising. Roberts was to patent an advertising device in 1930.

Key points of the Matthews story:

Now, in 1914 and faced with the prospect of a lengthy conflict, the British government was desperate for innovations which would help them wage war against Germany. Two inventions interested them greatly. The first was a ray which would disable the Zeppelins, and the second was a ray which could control unmanned craft. A reward of £25,000 was offered to the person who came up with either. Matthews was convinced he could provide the latter and claimed he had developed a remote control system using cells containing selenium. After testing his invention on Edgbaston Reservoir, he demonstrated it to Admiralty officials at Richmond Park’s Penn Pond. They were so impressed that Matthews received his cheque for £25,000 the following morning, a not inconsiderable sum of money in 1915.

Yet there was something not quite right about this event. Although the remote control boat had been proven to the Admiralty officials and a vast sum of money paid, the idea never manifested as workable in practice. The Admiralty, for whatever reason, chose not to pursue Matthews’ selenium control system which, besides operating boats remotely, was claimed to detonate explosives at a distance. Was this ignorance and jealousy on behalf of the War Office or the first hints that Matthews wasn’t quite as genuine as he appeared? Again Matthews lapsed into obscurity. He re-appeared briefly, yet significantly, in 1921, breaking new ground by producing the world’s first talking picture. This was a short interview with the explorer Ernest Shackleton prior to his fatal attempt at circumnavigating the Antarctic. This film is important because it proves Matthews, despite the hype and ambiguity which often attended his inventions, was not a charlatan, and was in many ways years ahead of his time.

Matthews turned his mind to the idea of a possible death ray in the autumn of 1923. After reading news reports of French airplanes dropping out of the sky over Germany, he said: “I realized that the Germans had found an invisible ray that put the magnetos of the aircraft out of action. I concentrated on efforts to discover what it was, and with the electric ray now at my command I think I have succeeded.” Select journalists were given a demonstration of Matthews’ ‘ray’ stopping a motor cycle engine at a distance of 50 ft (15m). “I am confident,” Matthews announced, “that if I have facilities for developing it I can stop aeroplanes in flight –- indeed I believe the ray is sufficiently powerful to destroy the air, to explode powder magazines, and destroy anything on which it rests.”

Thus the death ray was born in the mind of the popular press. Matthews capitalised on his new-found fame, being well aware that his stock was not particularly high with the British government. So, rather than approach them directly, he went to his old friends the press. They were only too happy to help, and fanciful accounts of the death ray and what it could do began to appear by late 1923. Bemused by Matthew’s sudden re-appearance but fearful that the publicity he was enjoying would lead to another nation bidding for the death ray, the War Office was forced to act. Swallowing their pride and suspending their disbelief, in February 1924 the Air Ministry offered Matthews the opportunity to demonstrate his death ray to them. Matthews at first ignored their advances, perhaps hoping the government would simply accept his assertion that the ray did as he said.

When no such offer was forthcoming, Matthews contacted the press with further dramatic claims and by April 1924 the death ray – or more properly the idea of the death ray – was world news. The London Star announced the invention as a “wonderful invisible ray which has turned into fact the dreams of Wells’ fiction.” And they hadn't even seen it yet! A wide-eyed Star reporter was ushered into Matthews’ London laboratory and shown a bowl of gunpowder being ignited by the ray. Matthews was at pains to explain this was only the beginning, a small scale demonstration of what could easily be the destruction of ammunition dumps at huge distances or the destruction of aeroplane engines in flight.

The scientific principles on which the ‘ray’ worked were glossed over by all concerned. Ionized air carrying an electrical current was mentioned by some commentators, others talked of exceptionally short radio waves. Matthews wasn’t saying and no-one appeared to be asking the right questions, certainly not the press. To them the idea of a death ray was enough.

Furthermore, Appleton claimed Matthews was “working the press, but had now lost control of it.” The explicit conclusion of this meeting was that the government did not trust Matthews. Yet they were loathe to dismiss him completely as long as even a small chance remained that he could be onto something. No government wanted to turn down the death ray only for it to turn up later in the arsenal of an enemy. Air Vice Marshal Salmond wrote immediately to Matthews suggesting further, more detailed demonstrations. Matthews replied that he could not understand why the government would not accept the evidence he had presented to them.

He had now lost patience with England and was offering the ‘ray’ to the French. Following this breakdown of communications, events took a turn that was both dramatic and ludicrous. Tuesday 27 May 1924 saw scenes which could have come straight from an Ealing Comedy. The Daily Express summed up the farce perfectly a day later with its front page headline “Melodramatic Death Ray Episodes”. Their lead article opined: “Melodrama has seldom surpassed the heights which were reached in yesterday’s ‘Death Ray’ episodes. Hurried legal action in the High Court was followed by an unsuccessful motor-car chase, an air journey by Mr. Grindell Matthews to Paris, a belated renewal of conversations on this side of the channel, a reopening of negotiations in France and a deluge of claims by rival inventors. Beneath all was the undertone of tragedy suggested by the terrible powers which are attributed to the ray.”

Once again, the government was forced by popular opinion to make official statements and on 28 May questions were asked in the House of Commons. Mr Leach, Under Secretary for Air, was questioned by Commander Kenworthy, who demanded to know what steps were being taken to prevent an invention of the death ray’s magnitude from leaving the country. Leach re-iterated the government's position, “We are not in a position to pass judgment on the value of this ray, because we have not been allowed to make proper tests. Therefore whether there is anything in it or not still remains unexplored. The Departments have been placed in a difficult position in dealing with the matter partly because of the vigorous Press campaign conducted on behalf of this gentleman, and partly because this is not the first occasion on which the inventor has put forward a scheme for which extravagant claims have been made. The result is the Departments are not able to accept Mr Grindell Matthews’ statement about this invention without a scrutiny which he is not prepared to face.”

Furthermore, His Majesty’s Government believed that “the conditions under which the demonstrations were made by Mr Matthews were such that it was not possible to form any opinion as to the value of the device.” Carefully worded or not, the implication seemed to be that Grindell Matthews at best may have not demonstrated his invention under correct laboratory conditions, and at worst had brazenly attempted to defraud the British Government. The statement went on to stress that the government had been at pains to be scrupulously fair with Matthews, offering him the chance to repeat the demonstration. All they required to be convinced was that he use his ray to stop the engine of a petrol driven motorcycle engine provided by them. On successful completion of this test, Matthews would then be given £1,000 as a retainer for 14 days whilst the government considered “the basis of further financial negotiations for the purchase or development of his invention.” As yet, the government didn’t even want to know how the ray worked, just for it to be demonstrated to their satisfaction using their own laboratory conditions. Not an unreasonable request.

The 1st of June 1924 saw Matthews returning to London, and he was angry. In an interview with the Sunday Express he defended his life’s work even to the point of raging at those who referred to his notorious invention as a ‘ray’. It was, he claimed, a ‘beam’, not a ray, although quite what the difference was he failed to say. Matthews still believed he had a deal with Royer and was insistent his death ray was all packed and ready to be shipped to France for further development.

From an entertainment perspective the film made great viewing, coming as it did in the wake of the massive publicity given the death ray furor. Yet there was no evidence that the subject matter of the film had any basis in reality. Stills show fantastic apparatus, claimed to be the death ray, but which bear no relation to the small Heath Robinson-like machine demonstrated to the government weeks earlier. Poetic license was clearly at work and S R Littlewood, in The Sphere, made some perceptive observations relevant to the whole affair: “…The Death Ray in which Mr Grindell Matthews is shown pulling levers of his machine and a rat is shown falling dead in its cage, a bicycle stopping and aeroplanes galore falling down in flames from the sky. From the scientific point of view – that is to say as a proof that it was the ray that killed the rat – I do not suppose that The Death Ray is intended to be regarded as of any value at all. One does not for a moment disbelieve Mr Grindell Matthews. At the same time a film which could have been so obviously ‘faked’ leaves one simply with the same amount of information as one had before save, perhaps, as to the shape of the machine, which is a sort of searchlight with three megaphone-like ears attached to it.

There the saga of the death ray ends. Matthews never managed to successfully demonstrate his invention to anyone's satisfaction. Whether this was because it was a complex money-making scam or whether the world’s governments were incapable of grasping the enormity of his ideas is unclear. We do know however that no-one ever developed a death ray, nor did Matthews pursue the invention further. Instead he went back to America where he worked as a consultant for Warner Brothers, putting his genuine skills in sound and vision technology to good use.

By the late 1920s, Matthews was back in Britain with a series of new, bold inventions which actually worked. His piece de resistance was a device to project advertisements on clouds.

On Christmas Eve 1930 he stunned London by projecting the image of an angel onto clouds above Hampstead Heath. The apparition was so realistic that people miles away apparently fell to their knees in worship, believing the Second Coming was at hand! He followed this with demonstrations in New York, where he projected the Stars and Stripes 10,000ft (3,000m) above the city (see below).

This invention clearly worked, yet once again Matthews was beset by problems. Although the invention could have revolutionised the emerging advertising industry, no-one seemed interested. Matthews had little time to reflect on this new failure as darker clouds were gathering and in 1931 he faced bankruptcy. His bankruptcy papers make interesting reading.

Financially secure again, he embarked on another series of inventions. Seeing that the Second World War was on the horizon, he began to develop the idea of ærial mines fired by rockets or suspended by barrage balloons. These, he claimed, could create an effective ærial ring of defence round cities such as London. This idea was discussed seriously by the government but never taken up as a practical proposal. Matthews’ mind, never still, then came up with the idea of the ‘stratoplane’ – a “plane which could fly on the edges of space.” He became a member of the British Interplanetary Society and actively pushed forward ideas which led eventually to the development of rocket technology.

Genius or charlatan, probably a little of both, Grindell Matthews inspired intense debate and massive publicity. Some of his inventions such as the talking films, ærophone and sky-projector certainly worked and were years ahead of their time. Other ideas such as his theories of space travel would come to fruition later in the 20th century.

What is it about early robot builders and "Death Rays"? Prof. Harry May, the person behind "Alpha the Robot" also claimed to have a "Death Ray."

See Alban J. Robert's later Mechanical Man here.

See all the Early Humanoid Robots here.

Greetings! Alban Roberts was my Great Uncle; my grandfather Arthur William Roberts was one of his brothers, and my father Selwyn Arthur Roberts was his nephew. Arthur, and Selwyn lived in Christchurch NZ, as do I. i would be interested in learning more of my ancestors including Alban's brother (or step brother?) Fletcher Roberts, and Howard Roberts who apparently was in the South African Police trooper, and died in the Boer War

Hi Laura,

Howard Harvey led a quadruple life (or more) – I have proof – contact me at cj.walter@bigpond.com

I am the son of Patricia Harvey (Walter)and Howard was her father in the 1920’s who followed from Eric Harvey born in 1914 – Howard married Coralie Mabel Tilley then had an affair with ….. lots more phone 0432141506

Hi Lesley and Reuben

Alban is my dad’s uncle. My dad’s dad was known as Howard Harvey as well. I have only recently discovered this. I can see where my 25 year old’s passion for electronics comes from now. I would love any photos you have of him.

Hi Mrs Wheeler,

Yes, I’d be very happy to receive more material on Alban Roberts. I’ve sent a separate email. I’m contactable on reubenh at cyberneticzoo.com .

Kind regards,

Reuben.

cyberne1

Also, i have some photos of Alban as a young man. Let me know if you would like me to send them to you. I have some other information i would be happy to send to you also.

Lesley

Thank you, Mrs Wheeler, for acknowledging my research on Alban Roberts. Alban played an important role in the early history of Mechanical Men / Automatons / and the beginnings of what is now called robotics. His work precedes some of the other, more well known ‘firsts’ in this respect.

Dear sir ,I am amazed at the research you have on Captain A.J.Roberts. My father was Howard Francis Roberts, a brother of Alban. There was

1 other brother, Fletcher, and 1 sister Saint Agness (Agness). All were born in New Zealand.

I was born when my father was 63, hence the age

difference. I actually met Fletcher and Agness in their later years. John Morrissey is a relative through the step-brothers of the family and lives in the U.S.A.

Yours, Mrs. Lesley Wheeler