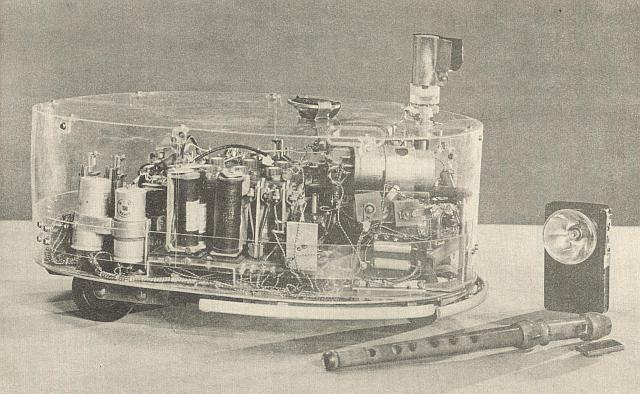

Image is from the December 1958 Teddington Conference on "The Mechanisation of Thought" proceedings by Blake and Uttley, Vol 2. London , in a chapter titled "Machine Reproducatrix" by Angyan, pp933-44 (see pdf below).

Although Angyan produce his dissertation paper on Conditioned Reflex in 1955, the first date of the models appearance that I can find is 1958 when he demonstrated itat the Teddington conference "Mechanisation of Thought" of that year. It may have appeared earlier as Daniel Muszka, of Szeged, Hungary, in 1956 was aware of Angyan's work in 'conditioned reflex' , and maybe even of his tortoise when he was starting to build his own labybug of the same year.

PDF from Teddington Conference here Dr. Angyan – Mechanisation of Thought Processes 1958 describes Machina Reproducatrix in detail.

Computer Oral History Collection, 1969-1973, 1977

Heinz Zemanek Interview, December 12, 1972, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

ZEMANEK:

es. Well, I got also into the Russian environment by–I was interested in cybernetics. I …got Wiener's Cybernetics; the old professor gave it as a present to me. I have the signature in and the date, so I know when it was: [15th January 1952]. When I had read that book I didn't know what cybernetics was, so I looked further on and I found that there were three real machines in existence, namely …Walters' Turtle, Ashby's Homeostat, and Shannon's mouse in the maze. And I started to do th[em] with my students. And I guess I'm the only man on earth who had copied all the three.

TROPP:

[Laugh].

ZEMANEK:

[Our] Homeostat … [is] a nice version, I happened to fall into a student who was in a plastic factory. So he could … shape everything very nicely. With the two others we did quite a development. Shannon's Mouse in the Maze we extended to have not only the information in what direction the mouse had left the field, but we added an algorithm concerning Ariadne's thread. Which is another two bit information. And with that the algorithm became complete, [avoiding looping and able to go back from the found goal to the start.] In the other case you would not know if–well, you would have to go into detail of that thing. So that was very nice. The other development was the artificial turtle. That, as you know, was the idea of just realizing as a little moving around circuitry an algorithm written down by Pavlov. Now I had, for some reason, the chance in 1959 to have [in Vienna] all that year a Hungarian specialist in conditioned reflex behavior, [A. J. Angyan]. And he would tell us all the stories and we would translate them, the student and I, into a circuitry, in an extended artificial turtle. On this there exists a paper in 1960 at the Fourth Conference on Information Theory in London.* … Now this was a very remarkable automaton because it had six state variables. So, in principle, it could react to the outside stimuli in sixty-four different ways. Now it didn't have all the sixty-four states. It had some forty states, but parts of them were not stable in time. They would jump back into more stable states. But still then the pattern of behavior was very complicated. But it really gave a model of the complete knowledge of the East and West school of behavioral sciences in the conditioned reflex field.

TROPP:

That's fascinating.

ZEMANEK:

Now, this was–I may make here a remark which relates to much later work, it was my first experience with the problem of translating from natural language descriptions into formal descriptions.[*Angyan, A. et al. 1961. "A Model for Neurophysical Functions." In: Fourth London Symposium on Informatyion Theory (C. Cherry, ed.). London: Butterworth. Pp. 270-284.]

Medical people, of course, don't have very much of an algebra to describe what they are doing. So the usual situation was we should say "we have understood what you have told us, we have formalized it." Then we gave examples. "If, if, if that happens on the outside, then, then, then the following would be the direction of the machine." And it happened very frequently that he would say, "yes, yes, yes–no, I haven't said that." We had said, "you didn't say it, but it's the clear logical conclusion of what we have derived from our talks." He said, "No, that's not at all so." So we had to re-phrase the early description and step by step we came then to something which was satisfying to him. We also became aware of the remainder which is always there if you go from informal speaking to formal. In the informal way you are not very precise. You have contradictions. But you cover a wider field, because you always can operate with a part of the knowledge, which is the active working of the brain. Doesn't need that much specification but has items in it which are larger, they are not worked out, but they are contents which the formal definition then would miss. So it was from that time on that I was very sensitive to any tension between formal and informal description, which was very helpful for my later language development. Now let us return, how does it come I moved into computers? As I say, I was interested and we did a number, we did at least two bigger relay machines. One was an analysis machine for logical functions. You willcertainly remember the work done in England by [McCallum and Smith of] Ferranti.* … And we did the same. … We had telephone equipment and [on this machine LRR1,**one] could program any Boolean expression, like on a telephone switchboard. And then the machine would run through…–up to seven variables, 128 combinations–and it would [indicate and store] "yes" or "no" [for each combination].

from "Beyond art: a third culture : a comparative study in cultures, art …, Issue 72" By Peter Weibel, Ludwig Múzeum (Budapest, Hungary – 2005)

Electronics began flirting with biology early on in the 1930s, and there were even forerunners in the nineteenth century. Actually, electricity began with biology and Galvani in the 1930s, its main purpose was telecommunication, and its goal was to learn from biology. The 1950s became the golden age of cooperation. and there is a familiar key word for it, cybernetics. Again, I may and must begin with myself, because I am the only one on earth who has built and further developed all three basic models with my students. They are the Artificial Tortoise. the Mouse in the Maze, and the Homeostat.

The artificial tortoise looks only slightly like a tortoise and was not intended to imitate one. Rather, it is a model for the conditioned reflex the Russian physiologist I. P. Pavlov developed the algorithms for it around 1890 When a dog sees food, the production of saliva in his mouth increases. This is an unconditioned reflex if a bell is rung at the same time (Pavlov used an electric door buzzer), the animal learns that the bell promises food, saliva production increases when the bell rings, even if no food Is visible. This is a conditioned reflex that disappears when the hope for food is not fulfilled often enough. Pavlov described the phenomenon, not as a formula but in prose. British neurologist W.G Walter recognized that this model Could be made electronically and built a little covered vehicle (hence the name tortoise), containing a lamp and whistle. Symbolizing food and sound respectively if the vehicle has an obstacle, the cover closes a contact; the model rolls back and tries again, adjusting a little more to the right or left. This creates the impression of animal behavior. The first Vienna model was a copy of Walter's model and represented Austria at the first cybernetics congress in Namur in 1956.

My medical partner for the next step was Hungarian neurologist and psychologist A.J. Angyan. He traveled with a more complex model of Walter's tortoise to a conference in London, the Mechanization of Thought Processes, in 1958 and stopped at our institute in Vienna in order to improve his somewhat poor model (at that time, cybernetics in the communist countries was still a bourgeois, decadent quasi-science, and Angyan could not obtain proper components). On his return trip, he decided in Vienna not to return to Hungary. but to apply for an American visa. During the waiting period, which lasted longer than expected (a good opportunity for us!), he not only cooperated with us as a team member in developing an expanded model for two connected conditioned reflexes but also obtained a grant from the Rockland State Hospital in New York City, which permitted him to live in Vienna and contribute a little to the costs — in return, the Hospital received one of the two models built. The student assistant was Hans Kretz. Altogether, we built more than five models of the tortoise in Vienna. The Rockland State Hospital was satisfied with the result, and, after Angyan finally got the visa for the U.S.A., he captured the interest of Warren McCulloch, who liked to support immigrants and took him under his wing. Angyan's further career was guaranteed.

Another variation, fully transistorized, was built in Vienna by a student, H. Bielowski. Interestingly enough, it turned out to be bigger, not smaller — that would be different today. This model was shown in the Austrian Pavilion at the World Expo in Montreal in 1981.

HANS KRETZ: An Interview Conducted by David Morton, IEEE History Center, 25 July 1996

Interview #283 for the IEEE History Center, The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, Inc.

Copyright Statement

This manuscript is being made available for research purposes only. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to the IEEE History Center. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of IEEE History Center.

Interview

INTERVIEW: Hans Kretz

INTERVIEWER: David Morton

PLACE: Vienna, Austria

DATE: July 25, 1996

Education and Cybernetics

Kretz:

I was born 1930, in Linz, in Upper Austria. After primary school and high school in Vienna I went to study telecommunication and electronics. In German we said "technique of low currents," a rather old-fashioned expression. I studied at the Technical University in Vienna, and graduated in 1960 as Diploma Engineer. My thesis was on a Cybernetic subject called the "artificial turtle." It was a model of neuropsychological functions. This is the more scientific description. I was engaged about two years to talk with a neuropsychological physician from Hungary. He told me what more or less simple animals are doing if certain stimuli are applied. And I made a block scheme out of his different remarks and descriptions. And afterwards I made the technical realization in the form of a small battery operated self-running model. It operated on different preconditions. I "taught" the model to build up so-called conditioned reflexes, as Pavlov's dog has done. From time to time it would "forget" something it had learned in previous periods and it could be shocked by strong stimulus, and so on. Afterwards I built two models. One for the young Hungarian who immigrated 1960 to the States and demonstrated his model at MIT, for instance. And people were very impressed but said the model was too small.

Morton:

What was his name?

Kretz:

Andrew Angyan. Later on, he was a physician in Los Angeles. Now I made another model for my university, the Technical University of Vienna. This model later on came to the Technical Museum of Vienna where my model can be seen together with a picture and a short description of myself. In this technical museum you can also see another cybernetics thesis, e.g. a model of a "mouse in a maze" after the principle developed by the Greek myth of Ariadne's thread, and also the famous "Mailuefterl." It's the first fully transistorized mainframe computer in Europe. Made at the technical university under the chief management of Professor Heinz Zemanek, a pioneer not only in Austria but at least in Europe of cybernetics and as well in computer questions. One of the most experienced in that respect. I myself was half a year afterwards a scientific assistant in this scope at the university. I had lectures in London at the Royal Academy and in Karlsruhe at the Nachrichtentechnische Gesellschaft. And later on there were several publications on this specialty. On the other hand my job meant to handle most modern topics.

——–end excerpt—-

[7] Kretz, H. 1961. "Vollständige Modelldarstellung des bedingten Reflexes" [Complete model of the conditioned reflex]. InLernende Automaten, NTG Fachtagung, Karlsruhe 1961, Munich, R. Oldenbourg, pp. 52-62.

[8] Kretz, H., A. J. Angyan and H. Zemanek. 1961. "A Model for Neurophysiological Functions,"Fourth London Symposium on Information Theory, London, Butterworth, pp. 270-284.

[9] Kretz, H. 1962. "Kybernetik-Brücke zwischen den Wissenschaften" [Cybernetics–bridge between the sciences] and "Modelldarstellung biologischer Verhaltensweisen" [Models of biological behavior].Umschau, pp. 193-195 and 240-242.