1912 – Dreadnought Wheel and "Big Lizzie" – Frank Bottrill

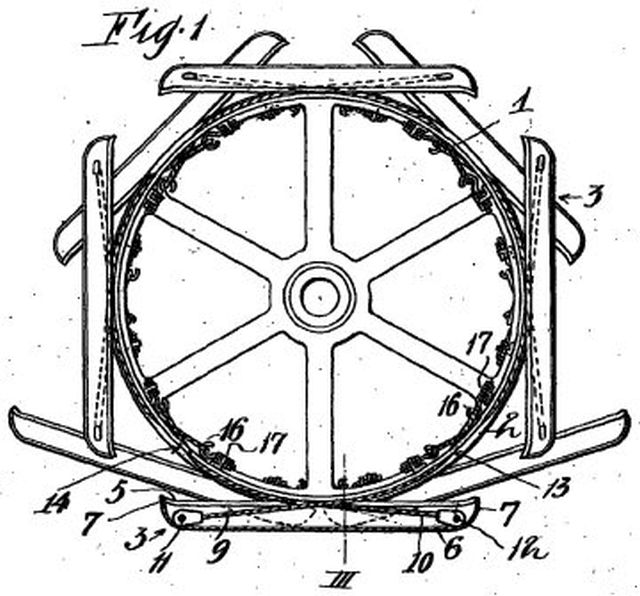

A dreadnaught wheel is a wheel with articulated rails attached at the rim to provide a firm footing for the wheel to roll over, they have also been known as endless railway wheels when fitted to road locomotives, and were commonly fitted to steam traction engines.

Prior to wide adoption of continuous track on vehicles, traction engines were cumbersome and not suited to crossing soft ground or the rough roads and farm tracks of the time. The "endless rails" were flat boards or steel plates loosely attached around the outer circumference of the wheel which spread the weight of the vehicle over a larger surface and hence were less likely to get bogged by sinking into soft ground or skidding on slippery tracks.

Some references also use the term pedrail, but the pedrail wheel of 1903 is a more complex arrangement that incorporates internal springing.

Bottrill referred to the rails as "ped-rail shoes".

[Note: Where text is from another source, I’ve left to spelling of “Dreadnought” as is i.e. “Dreadnaught”, which has become the more popular spelling.]

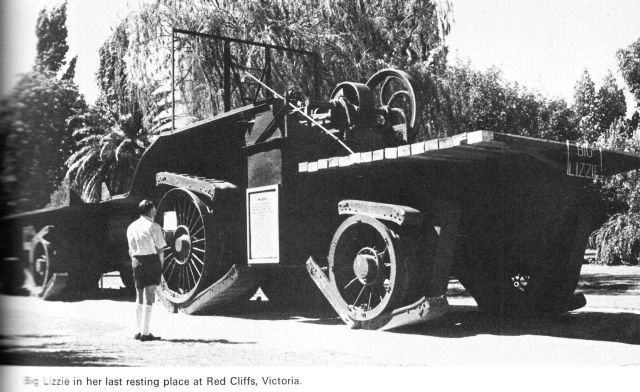

"Big Lizzie" at Red Cliffs, Victoria, Australia.

Children looking at one of "Big Lizzie's" massive wheels.

Image from Bottrill's British patent GB191208844 (A) ― 1912-10-17 .

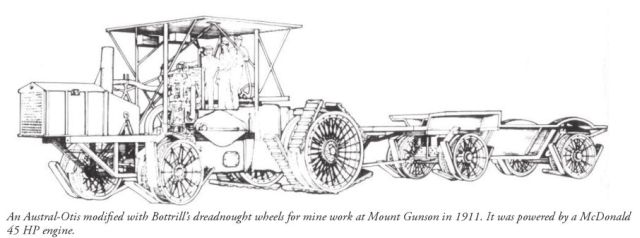

The smaller Austral-Otis Bottrill-wheeled tractor c1911.

Image source: Remarkable Australian Farm Machines: Ingenuity on the Land By Graeme R. Quick

From `Megaethon' to 'Big Lizzie':

Attempts to go where the roads do not

MOVING A HEAVY vehicle across country can have its problems. Unless the ground is very solid, the vehicle is likely to dig itself in and resist all attempts to move it further. Mud, sand and dust can all cause this.

The obvious solution is to increase the bearing surface in some way, so the wheels are less likely to dig their way into the ground under the vehicle's weight. If the vehicle can lay its own bearing surface in front of itself, then pick it up again after it has passed over it, so much the better.

One early attempt at this approach occurred in 1850 when a Hunter Valley farmer named Cleve had a steam engine built in Sydney. He decided to take it home under its own power on the iron shoes it laid down in succession in front of its wheels. Cleve called his machine the `Megaethon', but the Aborigines who saw it called it the 'buggy buggy'.

Eventually Cleve had to get some bullock teams to come and rescue his engine. Its great weight made its progress very difficult.

The idea cropped up again when steam-driven traction engines be common in Australia, about the turn of the century. Used to haul wagons across country, for ploughing and for stationary power at all sorts of locations, these machines faced the need to travel across country in all sorts of conditions. In 1906, Frank Bottrill patented 'an improved road wheel for vehicles and travelling machines, especially useful for traction engines'. He called it the Pedrail or Dreadnought wheel.

As Bottrill's wheel rotated it placed a series of bearers one at a time upon the ground. Each bearer formed a substantial flat bed while it was on the ground and prevented the wheel from sinking. The engine was therefore able to exert its full tractive effort. For use in very loose ground the bearers could be fitted with studs.

Some versions of Bottrill's wheel had two sets of bearers side by side. The bearers were attached to the wheel by a system of U-bolts and wire ropes that allowed them to move in relation to the wheel, but kept them rotating with it.

In 1907 Bottrill used a 30-horsepower International tractor fitted with his

Big Lizzie in her last resting place at Red Cliffs, Victoria.

Pedrail wheels to plough 202 hectares of mallee land for the Victorian Department of Agriculture and 38 hectares of virgin country at Howard's Plain, Victoria. Then he used a 70-horsepower McLaren traction engine with Pedrail wheels on a large-scale land-clearing operation at Tintinara for the South Australian Government. He pulled three large rollers covering a span of 18 metres and cleared an average of 12 hectares a day, and sometimes as many as 20 hectares. Later the South Australian Government bought rights from Bottrill to fit two of its steam tractors with his wheels. The Queensland Government also arranged to fit them to some of its equipment.

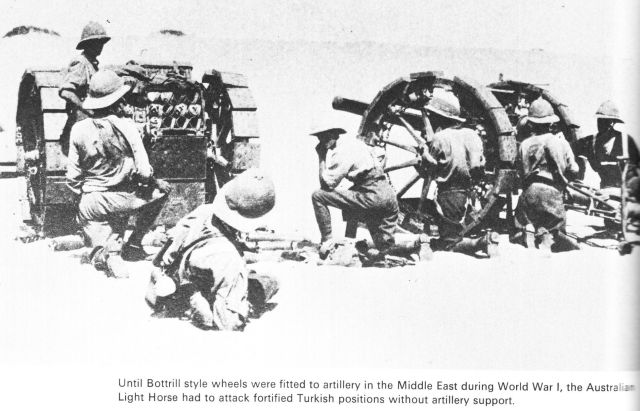

In World War I, the Australian Light Horse in Egypt had the Pedrail system fitted to its field guns so it could haul them across the desert. The heavy sand made transport of the guns on their ordinary wheels quite impracticable, and for a time General Chauvel was forced to conduct a mounted campaign against the Turks without artillery support. Once the Pedrail was adapted for desert conditions and fitted to the guns, the problem was overcome. Guns fitted with Pedrails were first used in the attack on Salmana in May 1916.

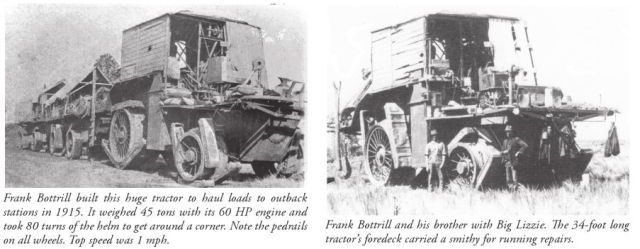

Bottrill's best known application of his Pedrail was to Big Lizzie, a giant traction engine now on display at Red Cliffs in Victoria's Sunraysia district. The massive machine, powered by a 60-horsepower Blackstone crude oil engine, was built in Melbourne in 1914. Its range of gears gave it four forward speeds from 0.8 to 3.2 km/h, and two reverse speeds, 0.4 and 0.8 km/h.

Until Bottrill style wheels were fitted to artillery in the Middle East during World War I, the Australia Light Horse had to attack fortified Turkish positions without artillery support.

Big Lizzie set out from Melbourne in 1915 and went via Echuca, Kerang, Swan Hill, Ouyen and Mildura. Everywhere she went, her owners had to get permission from the various shires. From Ouyen she travelled along a bush track made by bullock waggons beside the railway. This was the only road. Where the turns in the track were too sharp for her 61 metre turning circle, Big Lizzie just made her own track through the mallee scrub. Her big wheels carried her across even the sandiest country. She had a six weeks stop-over in Kerang while all her wheels were taken off and altered.

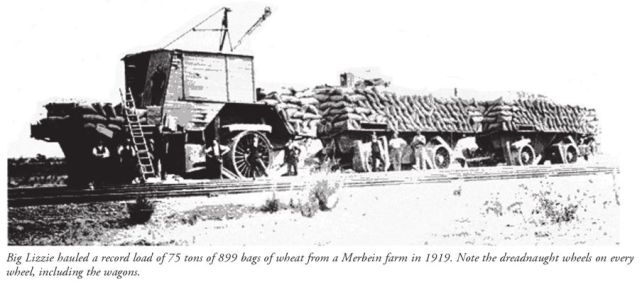

Big Lizzie arrived in Mildura in October 1917. She was unable to cross the Murray, which was in flood. No bridge or punt could carry her, so she went to work in the district, carrying wheat, one 1919 load running to 900 bags.

Big Lizzie herself was 10.2 m long, 3.4 m wide and 5.5 m high. She had two flat top trailers, each fitted with Bottrill wheels. Each trailer was 10m long, 3.4 m wide and 2m high.

When the Victorian Government decided to make farms for soldier settlers in the Sunraysia area during and after World War I, Big Lizzie helped clear land at South Merbein, West Merbein, Birdwoodton and Red Cliffs, a task that lasted until 1924. She cleared land in other parts of Victoria until 1929, when she was abandoned.

She was finally brought back and given her place of honour at Red Cliffs.

Source: Australian Inventory, Leo Port with Brian Murray.

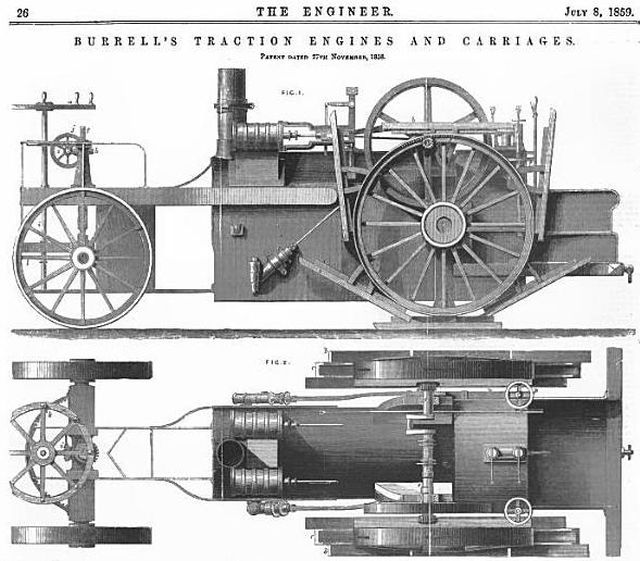

An early version was patented (British 11,357) by James Boydell in August 1846 and February 1854. Boydell worked with the British steam traction engine manufacturer Charles Burrell & Sons to produce road haulage engines from 1856 that used his continuous track design. Burrell later patented refinements of Boydell's design.

Boydell's design saw service with the British Army in the Crimean War where it was known as "The Megatherium war horse".

Source with references: Wiki

See other early Walking Wheels and Walking Machines here.

Re: 1912 – Dreadnought Wheel and “Big Lizzie” – Frank Bottrill (Australian) "One early attempt at this approach occurred in 1850 when a Hunter Valley farmer named Cleve had a steam engine built in Sydney. He decided to take it home under its own power on the iron shoes it laid down in succession in front of its wheels. Cleve called his machine the `Megaethon', but the Aborigines who saw it called it the 'buggy buggy'. Eventually Cleve had to get some bullock teams to come and rescue his engine. Its great weight made its progress very difficult." The "Megaethon" was built by Richard Garrett and Sons, Leiston, England, using Boydell's patent wheels. It was displayed at Chelmsford "Royal" Show in 1856. It was purchased by E. G. Clerk, of Bundarra, northern N.S.W., and shipped from England arriving in Sydney on 30 March 1857. After several demonstrations in Sydney the engine was shipped to Morpeth. After some delay, due to wet weather, the Megaethon departed Morpeth under its own steam, passing through Maitland on its way to Bundarra. Unfortunately, becoming disabled near Singleton, it was hitched to a team of bullocks for the remainder of the journey, arriving at his property "Clerkness," Bundarra, in November, 1857. It was here thatt the natives gave it the name "buggy buggy."