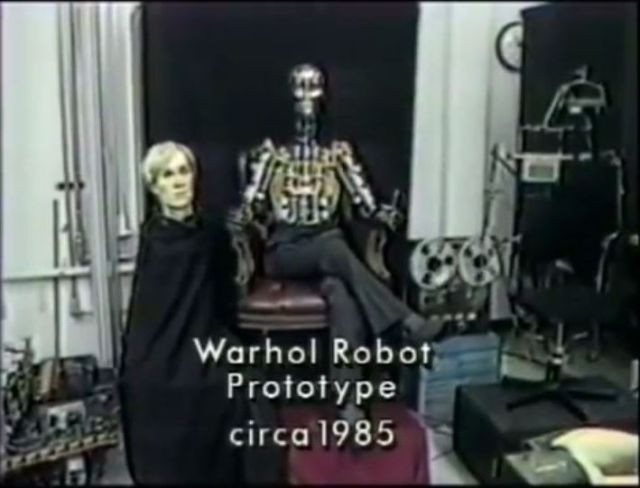

1982 – "A2W2" the Andy Warhol Robot.

"I want to be a machine, and I feel that whatever I do and do machine-like is what I want to do. I think everybody should be a machine."

Andy Warhol, Nov 1963.

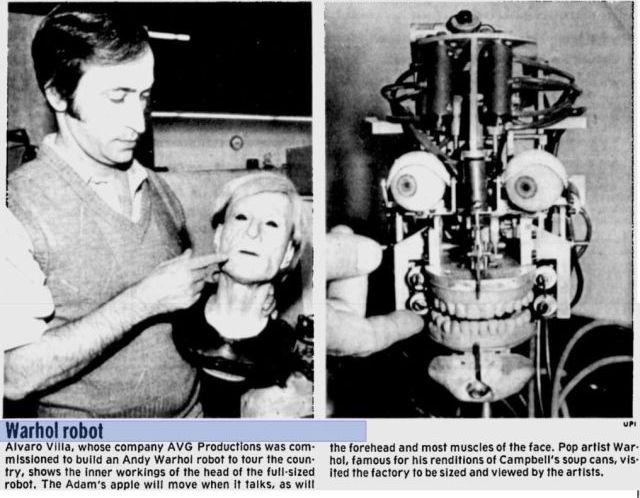

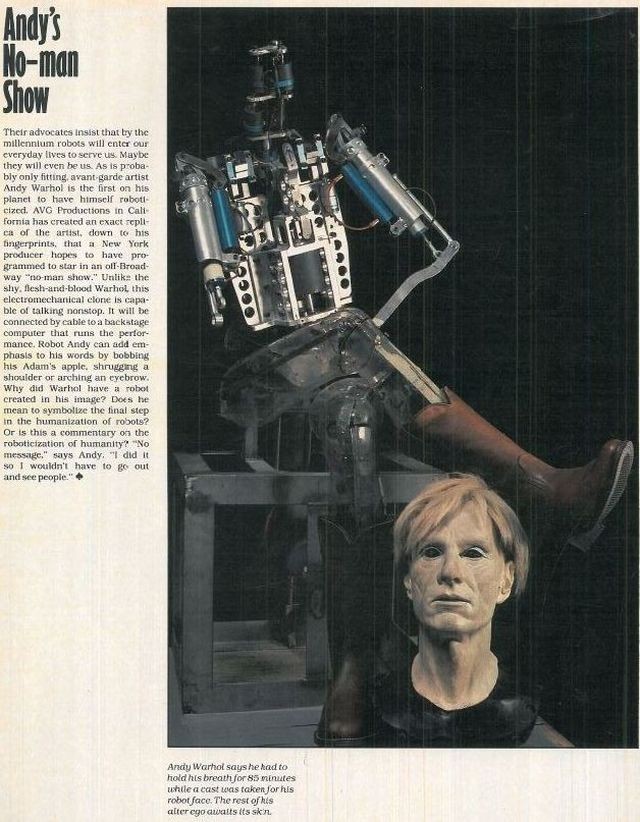

Source: Times Daily, Oct 30, 1982.

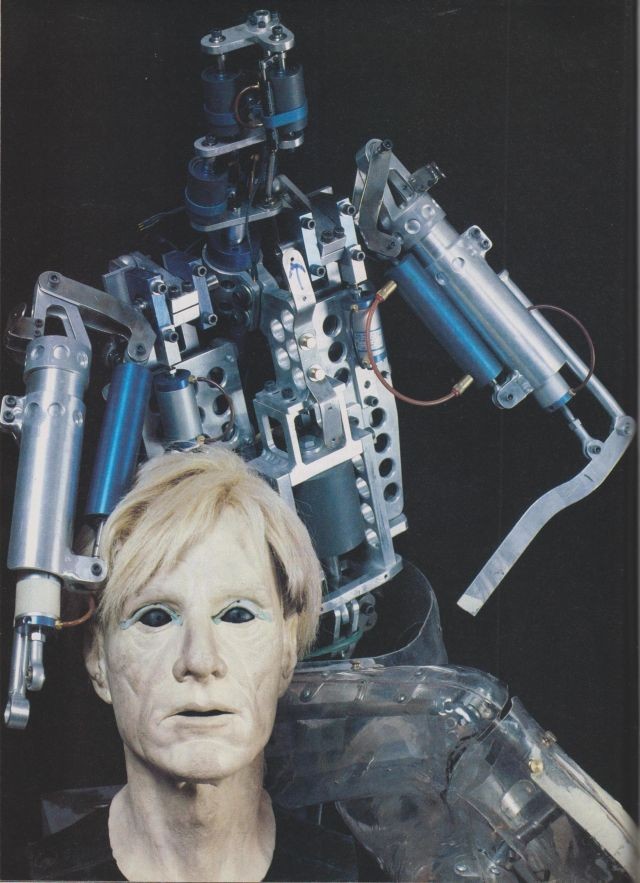

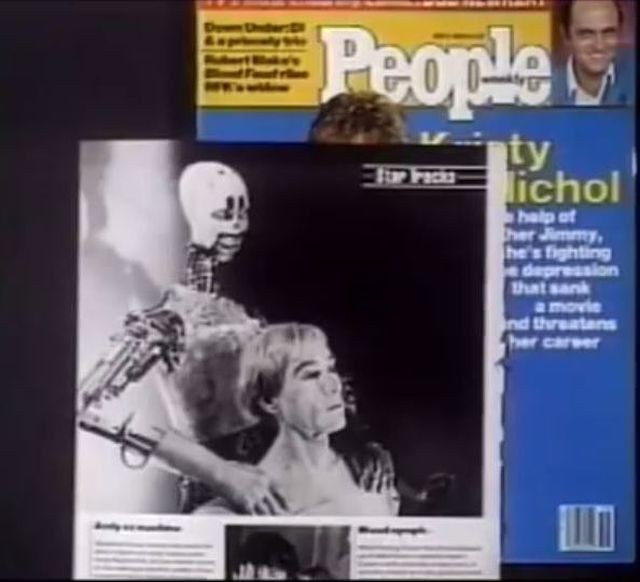

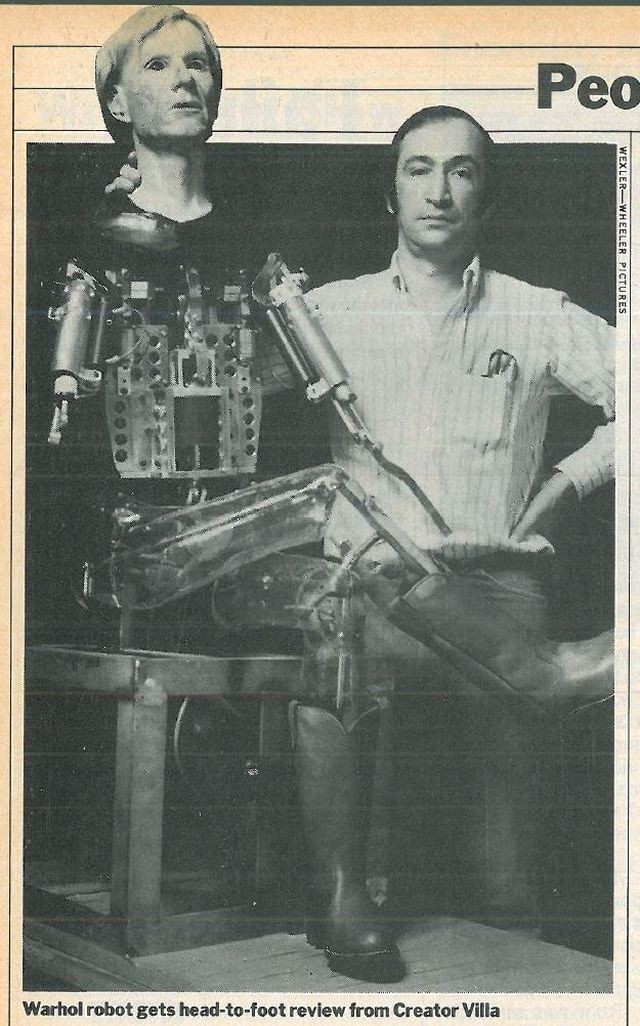

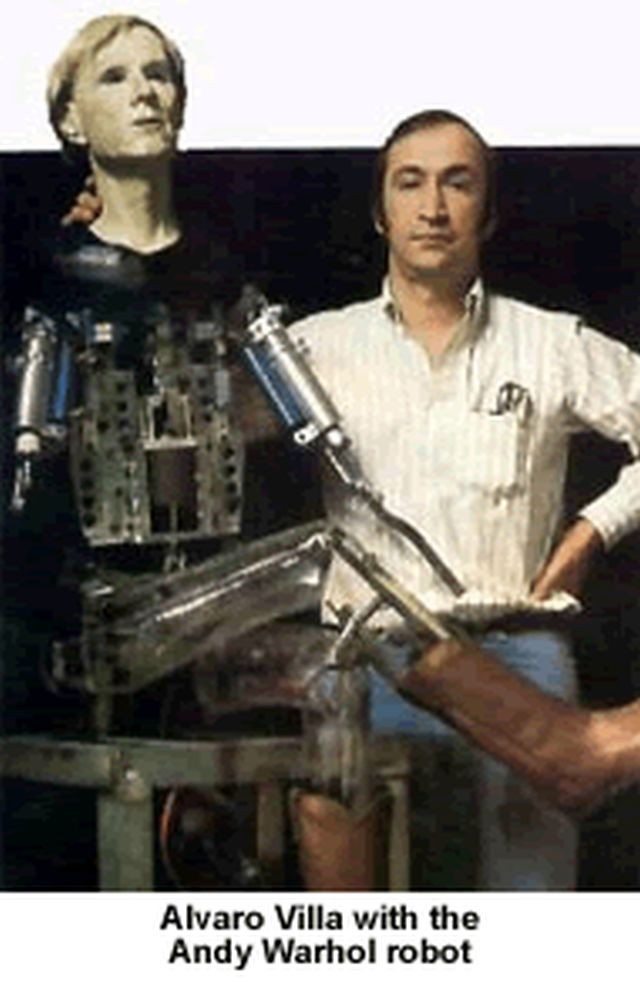

Alvaro Villa with some of his animatronic figures.

Image source: Life Magazine, Dec, 1984. Photography by Eric Wexler.

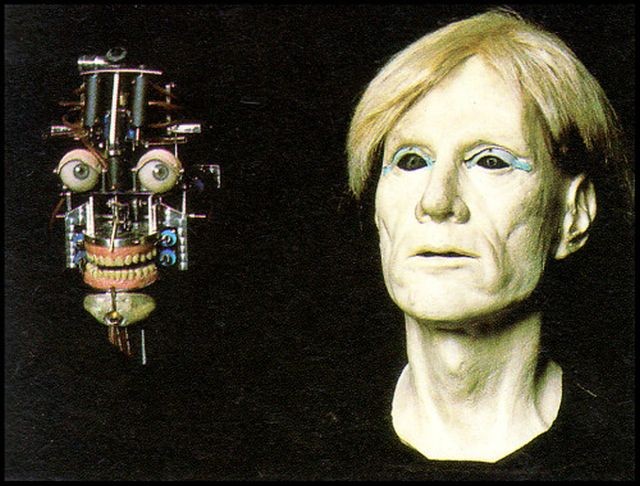

Image source: TIME Nov. 15, 1982. Photography by Eric Wexler.

Text Source: Robots, machines in man's image, – Page 117, Isaac Asimov, Karen A. Frenkel – 1985

…There are animated figures in Disneyland and Epcot Center. Robots promote products at trade shows. Hollywood has created robot film characters, and an Andy Warhol robot will soon make its Broadway debut. There is a kind of "information ricochet" (to use Tom Wolfe's phrase) among developers of these robotlike amusements, who become inspired by one another's creations.

One day while walking through New York's Pennsylvania Station, Broadway producer Lewis Allen happened upon a promotional robot for Columbia Picture's film The Greatest. The robot was a Muhammad Ali look-alike that so fascinated Allen that he imagined it could come to life. Allen had also been reading two books by pop artist Andy Warhol, Andy Warhol's Exposures and The Philosophy of Andy Warhol, and was searching for a way to adapt them for theatrical production.

Allen perceived Warhol as trying to reduce himself to a camera and a tape recorder. Since Warhol has often said that his ambition in life is to become a machine, Allen decided to build a robot in Warhol's image. He approached Walt Disney Productions, but they were gearing up for Epcot Center and were themselves looking for technicians. Allen also approached George Lucas, but the Star Wars producer was interested in robots for film only. Finally, Allen hired computer consultant Gerald Feil and Alvaro Villa, a one-time Disney engineer, to build the robot. Both had experience in special effects and animation design films and live tours of animated figures. Work on the robot's hardware began in Villa's company, AVG Productions – Valencia, California, in 1981, while Robert Shapiro, president of Meta Information Applications in New York City began working on the software. The screenplay was written by playwright-producer Peter Sellers, who worked on Allen's most recent Broadway hit, My One and Only.

The Warhol mechanical clone will star in a show called Andy Warhol's Overexposed: A No Man Show that will on Broadway in September 1985. The robot will have fifty-four movements, ranging from facial expressions to folding its arms. These will be synchronized with recordings of Warhol's voice. All of this will be controlled by a specially built computer, "because nobody builds one for animated figures," says Villa.

The robot will be seated on its bed in Warhol's rom, surrounded by its dog, a telephone, and two television sets. It will interact with these as well as with the audience. When a member of the audience asks a question, the robot will have five preprogrammed answers to choose from.

Besides being entertaining, Allen says, the show may indicate that art and technology are not necessarily pitted against each other. Other questions Sellers says it may raise are: What is the difference between a robot and a human being? What happens when a human being becomes a robot? What happens when a robot tries to become a human being?

1982 – "A2W2" the Andy Warhol Robot – Lewis Allen/Alvaro Villa.

The Automated Andy Warhol Is Reprogrammed

May 16, 2002|AL RIDENOUR | SPECIAL TO THE LA TIMES

As the Museum of Contemporary Art primps this month for the only American exhibition of the Andy Warhol retrospective, another Warhol sits on the sidelines, a twin in Chatsworth ready to leave home as soon as his programming is complete.

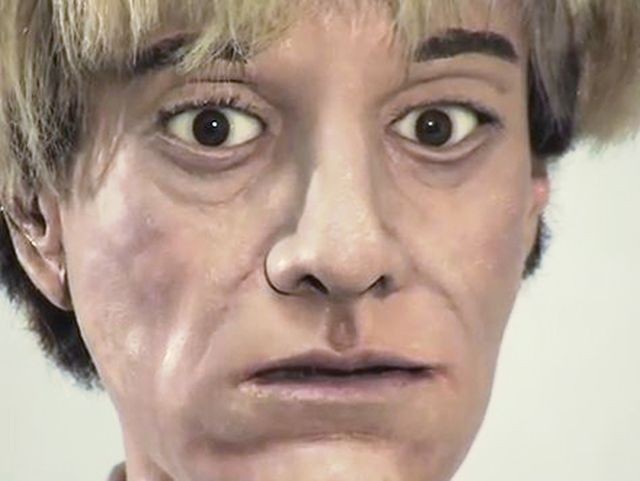

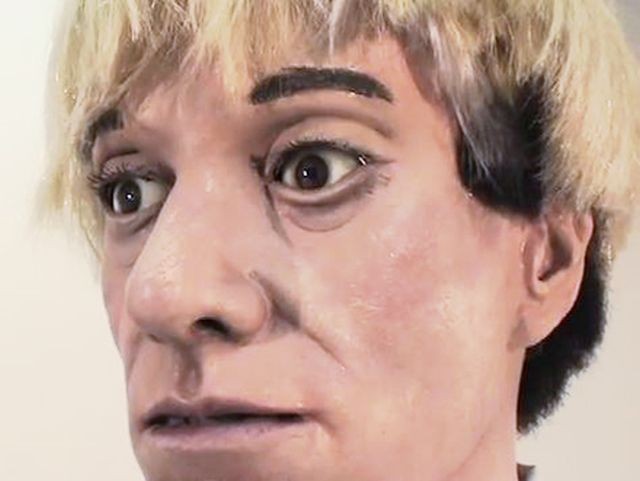

The resemblance is uncanny: the hair identically chopped, the mole precisely placed and the skin equally pasty, even if it is silicone. Below the neckline, however, the celebrity likeness dissolves into a tangle of hydraulic tubing, electronic actuators and aluminum bones.

Fabricated in 1982 for a production that never left the ground, this robotic Andy Warhol has lingered for 20 years at AVG, a firm that designs and fabricates mechanical characters for movies, theme parks and exhibitions. A deal was struck with a private collector last month, and the robot is being prepped for the handoff. Alvaro Villa, who worked for Disney Imagineering and founded AVG in 1978, said he will miss his animatronic Andy, adding, "It's become a sort of icon for the company."

Villa says the Andy Warhol Museum in the artist's hometown of Pittsburgh had expressed interest in acquiring the robot but made no counteroffer when a private collector approached Villa unexpectedly. Preferring not to give the amount of the sale, Villa says the buyer disclosed little.

"He was very mysterious," Villa says. "I honestly can't even tell you his nationality because another person came to negotiate for him."

Museum director Thomas Sokolowski admits to a fascination with the robot but says he is not convinced it would have been a good investment. "It could distract from the experience of the paintings rather than enhance it. Particularly for Americans today, a Madame Tussaud's or robotic light show is far more exotic than any painting."

The mechanical figure was created as the star of a touring multimedia stage production to be co-produced by Warhol and Broadway impresario Lewis Allen. Tentatively titled "Andy Warhol's Overexposed: A No-Man Show," the automated theatrical curiosity was to have cost an estimated $1.25 million, but funds never materialized. Sokolowski says the production was to have depicted the artist's daily routine of sitting in bed while dictating his diaries over the phone.

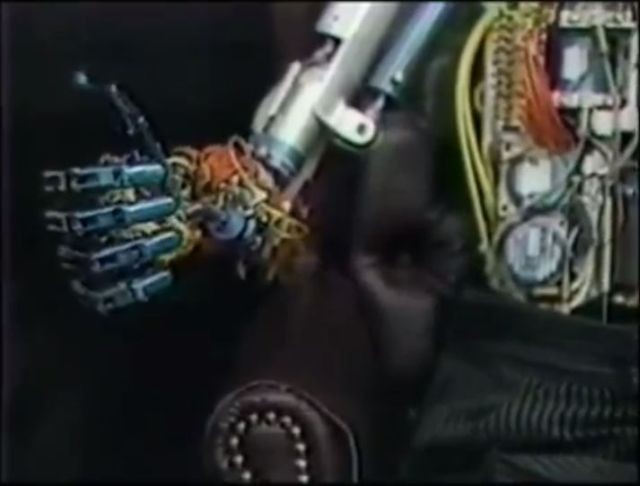

Villa never saw a script and never got as far as programming the lip-sync, but other functions are complete, including 54 movements ranging from shrugging shoulders to a bobbing Adam's apple. He also recalls preliminary discussions about making robotic dachshunds to stand in for Warhol's pets, Amos and Archie.

The yearlong process of creating the $400,000 robot-actor began with the actor's visit, when his voice was recorded, his motion videotaped and his body photographed from hundreds of angles. John Davis, who then headed the company's sculpture department, recalls Warhol enduring measurements with calipers and sitting for photographs with stickers attached to the pivot point of his jaw. "He was very patient and quiet," he says, "and I think I'd have to call him shy." Castings were taken from Warhol's hands to duplicate detail down to the fingerprints.

Using the photographic reference, Davis sculpted a head around custom eyeballs and off-the-shelf teeth from a dental supplier. From this, he created molds and cast rubber skins as well as a fiberglass skull that would support the bonier parts of the face. A body with removable panels was cast in plastic, and this hollow shell then went to the AVG mechanics responsible for devising a motorized musculature. The completed figure was then airbrushed, clothed and topped with a Warhol-esque wig.

So why didn't the robot see its 15 minutes of fame?

Sokolowski says that investors could not be convinced that all technical issues had been resolved. "Could the show pay for touring costs? Would the robot break down? Would you have to pay 40 technicians to come along?" These, according to Sokolowski, were real concerns, along with the fear that the robot's technological sophistication would be outdated before the curtain ever rose.

Robot's Monologue Was Never Created

The no-man show, Sokolowski says, was the brainchild of director Peter Sellars, who intended to write a script based on the artist's diaries and two of his books, "The Philosophy of Andy Warhol" and "Exposures." But Warhol never recorded a monologue and, after his death in 1987, plans to have an actor read the lines or to edit something from existing recordings by Warhol didn't materialize.

The notion of casting a robot to play the artist may have been sparked by Warhol, who declared in the 1960s that he would like to be a robot or machine. "In many ways, it wasn't that great a stretch. Just look at tapes of him being measured for the project," Sokolowski says. "His movements are very wooden, almost robotic."

As the robot was being built, Warhol was (in his own way) enthusiastic, expressing the hope that his mechanical counterpart could take over the burden of public appearances. The idea may have been more than a joke to Warhol, who in 1967 hired his Factory crony Alan Midgette, to impersonate him for a college lecture tour.

"He thought as long as someone looked like Warhol and sounded like Warhol, people didn't really care since they were having the Warhol experience," Sokolowski says, noting that the artist's robot remark could also be understood in terms of social programming.

"Look at it as following all the patterns that our society made for us: buying the right perfume or clothes to fit a particular role." This sort of robotic obedience, he says, was hardly anathema to Warhol. "He came from the wrong side of the tracks, and he himself had to learn how to talk hip, be cool, fit in. He embraced that process."

The fact that Warhol dubbed his studio the Factory, Sokolowski says, also alludes to the artist's love of predictable mechanized process. Repetitive behavior may, in fact, have been symptomatic of his psychology.

"This is not definitive, but we think he suffered from something called Asperger Syndrome, a very, very mild form of autism. So the fact that Warhol would do these repetitive things, like only eat one food for lunch every day, wear exactly the same kind of underwear for 30 years or fiddle with a rosary in his pocket, is also significant in that sense."

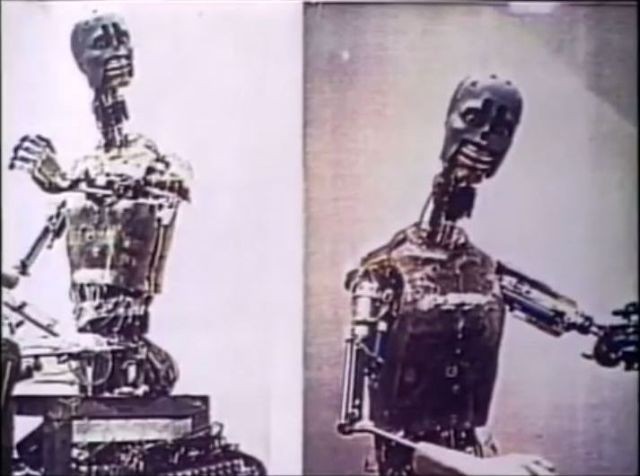

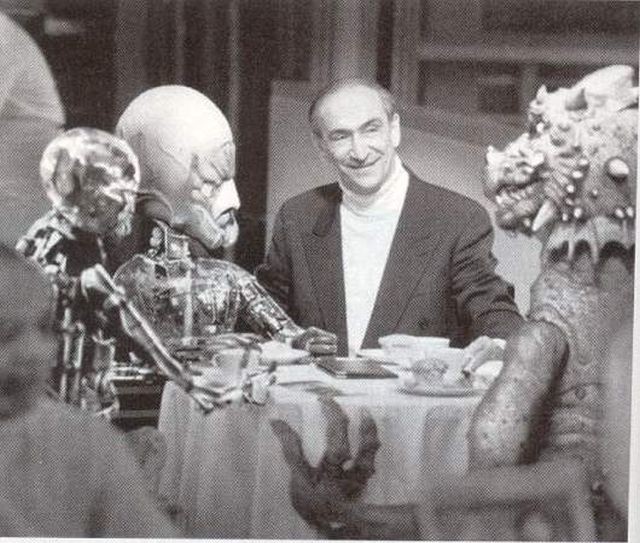

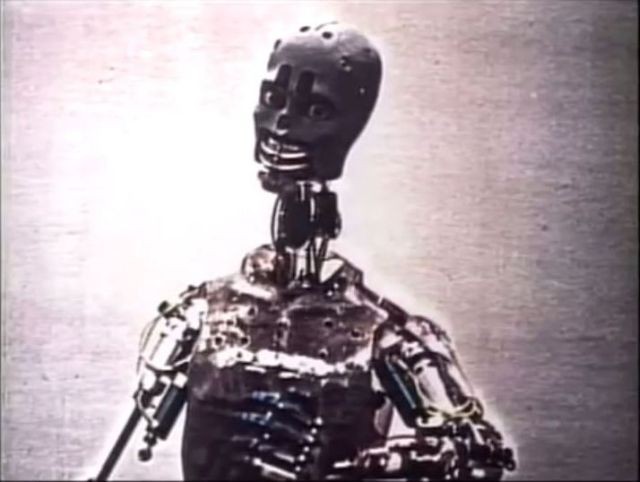

As Warhol's mechanized double says goodbye to theatrical aspirations, Villa is parting not only with a company icon, but also with a useful model. After the original rubber skin deteriorated and peeled away around the time of the artist's death, the exposed high-tech skeleton went to work on TV, appearing as a background extra in an episode of Warner Bros. "Lois and Clark" and in the Discovery Channel documentary "Robots Rising."

But its role as far as AVG is concerned is larger than that. Villa explains by conducting a tour of the company's machine shop. Next to a rack of bins, he points out something that looks like a robotic anatomy chart, each bone and muscle coded with a number corresponding to a particular bin.

"We have a sort of standard design for human figures," he says, pulling out a box that seems to be filled with metallic finger bones. "Andy was the first sophisticated human figure built by the company," he says. "We refined his design over the years, but many of the parts still come from him."

AVG has created roughly 1,000 robots since 1978–dragons, singing flowers, even industrial workers to sew for Singer–and among them are many human-like descendants of Warhol, including an Albert Einstein, a Wizard of Oz, a Sinbad and even a replica of the ghoulish host of "Tales From the Crypt." So even if the animatronic Andy is retiring to private life, little bits of Warhol will continue to be dispersed around the globe, in AVG robots from Las Vegas to Tokyo to Seoul.

A Popular Mechanics Special Section

NEWSCIENCE/INNOVATIONS

Will the real Andy Warhol please stand up and say something?

It's all there, The affectless gaze.

The diffracted grace … the bored languor, the wasted pallor … the chic freakiness … the chalky, puckish mask, the slightly Slavic look, The shaggy, silver-white hair, It's all there. Nothing is missing. I'm everything my scrapbook says I am."

The words are Andy Warhol's, and he's describing himself, But if all goes as planned, he could also be talking about A2W2, the Andy Warhol robot so lifelike—at least so Warhol-like—you'll have trouble telling the two apart,

The android Warhol, to be built at an estimated cost of $400,000, will have a role in life as soon as it's born: It will star in a one-robot show, perhaps 45 minutes long. Producer Lewis Allen, who was one of the producers of Annie and My One and Only, hopes to open on Broadway this fall.

Explains Allen, "The robot will be seated in Andy's room, with the telephone and a couple of television sets behind him, and he'll simply talk. Then there'll be a section where the audience asks him questions, and he can reply. The last part will be a kind of probing of himself as a person. But, of course, it will be a robot doing it."

The robot will operate only in a seated position, but according to Allen it will be able to do everything a seated human can do: "The mouth will move, the eyelids will open and close. And it will be synchronized and move as an organic unit, so that when it moves an arm forward, the rest of the body will compensate. Plus there will be a kind of sensory feedback: If it's going to pick up a phone or a glass, it will have the sense to apply the right kind of pressure to lift without crushing. It will move the way Andy moves and talk in his voice. It will even stutter,"

Allen is A2W2's godfather; its technological parents are several. The robot is being constructed by AVG Productions, of Valencia, California, whose president, Alvaro Villa, helped create many of the animated figures in Disneyland. Villa had Warhol come to his office to be photographed and measured in detail. "Then we made a sculpture of him out of clay and a fiberglass mold from the sculpture," Villa explains. "We used the mold to make clear plastic shells for the chest and limbs, including every last detail. We even included details of his fingerprints, and we're making dentures to match his teeth."

The robot's body will be made of clear plastic so that the mechanisms inside remain visible (when not covered with clothes). But the face and hands will be covered with a flexible, skinlike material.

Disneyland's robots work on hydraulics (moving because of internal pressure from a liquid); A2W2 will work on pneumatics (pressure from a gas). Says Villa, "Pneumatic machinery is much more complex, but it breaks down much less often." Inside the ersatz Warhol, valves at the base of a pneumatic cylinder will be connected to mechanical activators that will manipulate A2W2's face and limbs. The robot's actions will be controlled by microprocessors.

The computerized program to direct the microprocessors is being designed by Robert Shapiro, once a senior mathematician-programmer for IBM, now head of a consulting business, Meta Information Applications, of New York City. "The robot's speech will be synchronized perfectly to its lip movements," says Shapiro. "The speech is completely digitalized and controlled by the computer. This means that it's possible for the robot to choose different things to say under different circumstances. It's like a word processor, where you can move a sentence around. If you move a sentence around in our system, the system understands the motions and utterances that are connected with that sentence—it knows what Andy sounds and looks like saying those words."

The system will only be able to move sentences, however, not single words or syllables. This will avoid the disjointed, inhuman sound of most synthesized speech. Warhol will record the voice himself. Says the artist, "I was hoping they'd use someone else's voice. I don't like my voice, but I guess I'll have to talk for the recording."

Producer Allen got the idea for A2W2 from Warhol's books: "Andy has always said, 'I'd always wanted to be a machine,' " he explains. "He carries a camera and a tape recorder around with him all the time, and he tries to remove himself more and more as a person, I think, in a funny way, he has anticipated the computerization and robotization that's been happening in our society. So I thought, why not use a robot of Andy to dramatize his philosophy? It's an implicit comment on what's happening in the world."

Says Warhol, "I think if the robot goes on talk shows for me, it'd be great."

Source: POPULAR MECHANICS • APRIL 1984

ANDY WARHOL ROBOT IN LIVERPOOL

Andy Warhol Robot

The Andy Warhol robot is on display at the Tate Museum in Liverpool through May 2004 as part of the Mike Kelley: The Uncanny exhibition.

The robot was designed by Alvaro Villa shortly before Warhol's death for use in a stage show titled Andy Warhol: A No Man Show based on Warhol's books, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again) and Exposures. The production was to be produced for Broadway by Lewis Allen of Annie fame, but the project was cancelled after Warhol's death. (Mr. Allen passed away in December of last year).

Bob Colacello: "… there was a big project that Fred [Hughes] killed after Andy died. Lewis Allen, who was the producer of Annie and of Tru, the Truman Capote one-man show, had taken an option on the Philosophy of Andy Warhol and Exposures and had this wonderful idea to make the two books into something called Andy Warhol: A No Man Show. It was going to be a robot of Andy sitting on stage just gossiping and philosophizing based on the text of those two books. Peter Sellars was going to direct it. But the technology kept moving so quickly that every time Lew thought he had a robot, they'd find they could make an even more advanced robot, which would have eleven hand movements instead of three hand movements. And so he'd actually invest more money to get a better robot and then that would put the whole project back a year or two.

Andy loved this idea; he loved the fact that there was going to be this Andy Warhol robot that he could send on lecture tours. It could do talk shows for him. The idea was that the show, if it was successful in New York, could then also simultaneously be running in London, Los Angeles, Tokyo with cloned robots. And people would actually be able to ask questions of the robot, which would be programmed with a variety of answers. The whole thing was so Warholian and so perfect.

But when Andy died, Fred refused to renew the option. I owned fifty percent of Philosophy and Exposures, and Andy owned fifty percent after he died. In any case, the deal was killed. I think that Fred didn't want this Warhol robot haunting his existence. It's a shame. It really would have been the greatest thing that could have happened for Andy. It would have almost been like coming back from the dead. And he really loved the project. He sat for hours at some high-tech place in the San Fernando Valley where thy made a mold of his face and his hands… there's a whole photo session of it. (BC)

Source: Angie Waller.

Andy Warhol Robot, 2007

Documentation of the Andy Warhol robot designed by Alvaro Villa. The project was underway shortly before Warhol’s death for use in a stage show titled Andy Warhol: A No Man Show based on Warhol’s books, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again) and Exposures. Production of the robot was cancelled after Warhol’s death. The robot is now twenty years old and its outdated technology puts it between the realms of uncanny and absurd. Andy Warhol Robot documents Alvaro Villa, the inventor, demonstrating the robot's movement and audio features. The jerky motion and low fidelity audio make Warhol’s pre-recorded “I don’t know” responses sound something like an animatronic Chucky Cheese character or a séance with the dead.

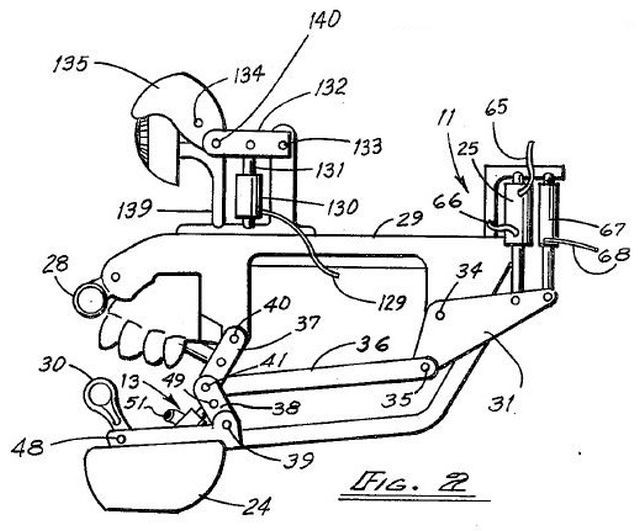

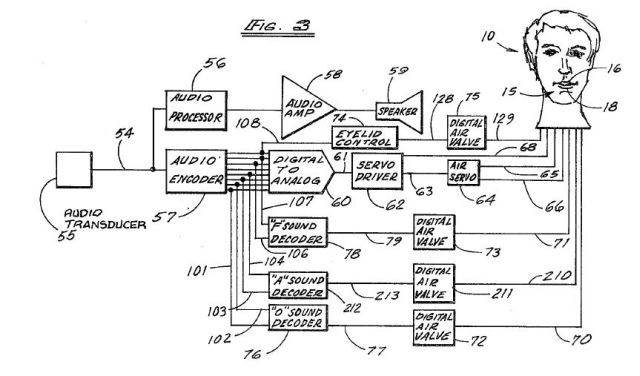

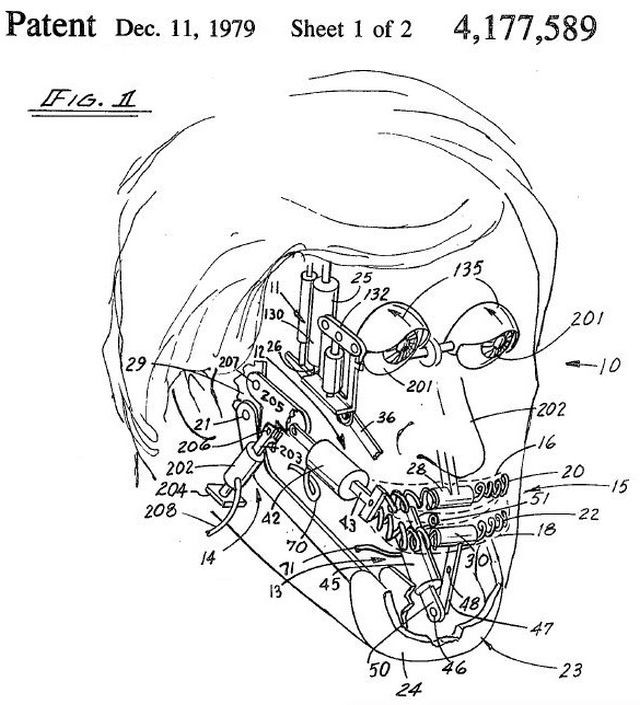

An Alvaro Villa animatronic patent when he worked for Disney's Imagineering.

Publication number US4177589 A

Publication date 11 Dec 1979

Filing date 11 Oct 1977

Inventor Alvaro J. Villa

Original Assignee Walt Disney Productions

Three-dimensional animated facial control

Abstract

An artificially animated face with three-dimensional facial features formed of a flexible material is provided with remotely actuable concealed mechanisms for manipulating the jaw, rounding the mouth, and drawing the lower lip inward relative to the upper lip. The face is operated by an audio input either from a microphone or from an audio tape. The audio input is fed both through an audio amplification system to a speaker located proximate to the face, and also to an audio encoder which senses the major frequencies of the spoken sounds of the audio input and produces one or more digital signals in response thereto. If an "F" sound is detected, the lower lip of the figure is drawn inward to a slight degree, thus simulating human lip movement in sounding the consonant "F". If the decoder detects an "O" sound, the mouth is rounded in response thereto. If the decoder detects an "A" sound, the mouth is drawn into a line. The eyes of the figure may be blinked upon receipt of a specified number of digital signals, and a wind jet may be operated in tandem with the mechanism for drawing the lower lip inward to simulate the expulsion of air from the mouth in conjunction with an "F" sound.