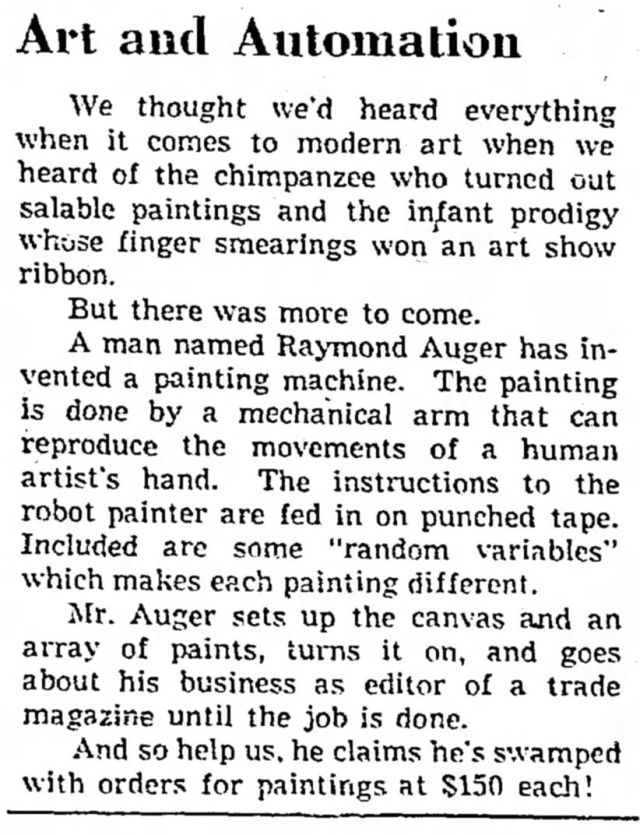

Press Photo of Raymond Auger's Painting Machine 1962.

ROBOT ART: "Take home a machine-made painting while U want it," reads the sign over the door of the "Automatic Art Show" in a shop in New York's Greenwich Village. Presiding over it is Raymond Auger, a bearded painter who believes in giving art a new mechanical twist. The machine is indeed unusual. Its actions, like those of a pianola, are dictated by a heavily punctured roll of thickened paper running through its "brain." Attached is an armature which opens and shuts, grabs the brushes, dips them in four paint pots containing black, red, blue and yellow, and revolves on a rotating stand. Thus armed it attacks the canvas. SEP 16 1962

Raymond N. Auger developed his painting machine between 1955 and 1959.

Newspaper Source: The Salt Lake Tribune , August 23, 1960

(Source: MI or SM March 1962)

Keeping busy between paintings…

The Bee, 11 Mar 1964

An Arty Squeeze Toothpaste Test Failure Leads to Art Brush-Up

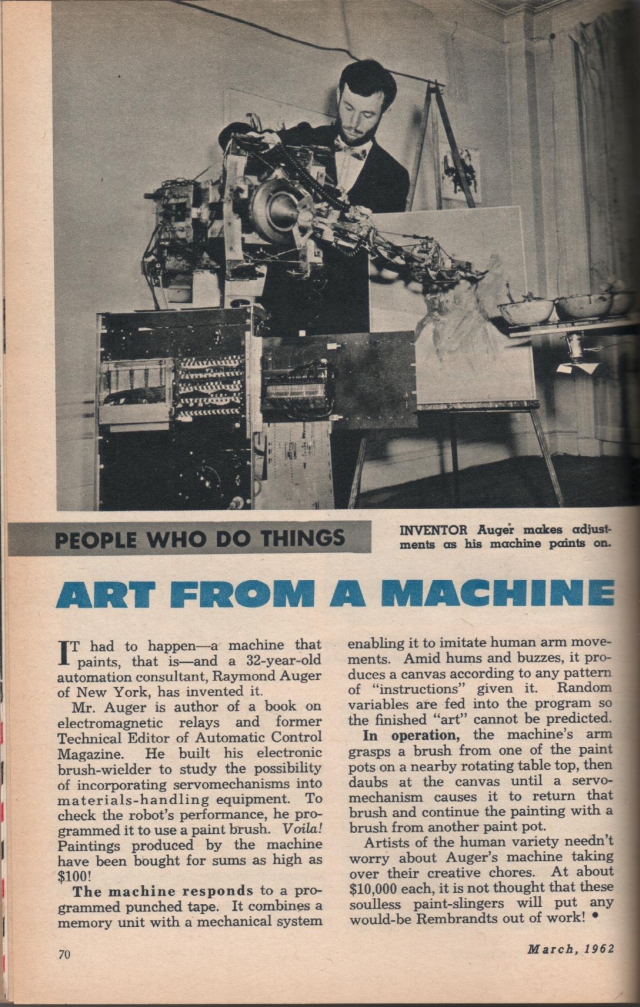

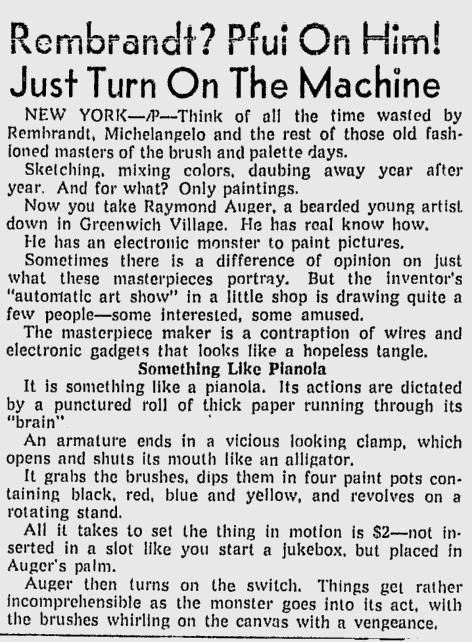

RAYMOND N. AUGER ran into an unexpected cavity when he invented a mechanical arm to stuff toothpaste into tubes. As a result, he has become one of the most novel art dealers in New York's Greenwich Village.

The hole in Auger's original plan was the objection to automation in toothpaste stuffing by live workers on the assembly line. Auger, an automatic control systems expert, decided to turn the talents of his invention to painting. He found that the sensitive stroking, poking and dabbing motions of the tape-controlled arm were perfect for turning out art works.

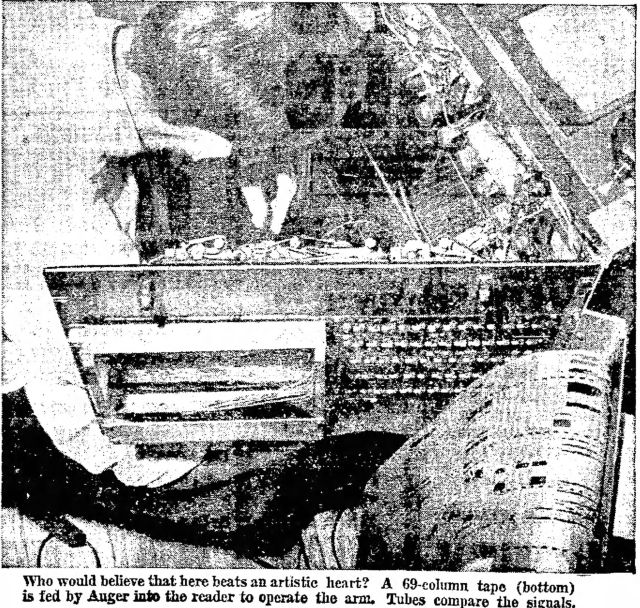

A tape with 69 columns is fed into a reader which passes on coded control signals to the arm. Cables, acting as tendons, are pulled by a clutch and chain system. A camel's-hair brush has replaced the toothpaste tube in the arm's fist and paints are sitting in for the dentifrice. The arm, is ready to create.

Auger, who may be writing a new chapter in the history of Dadaism with his mechanical arm, has sold hundreds of the colorful paintings to residents and visitors in Greenwich Village. No two paintings are alike and prices for each work range upward from $150.

A brushoff by the toothpaste industry has left an inventor with the sweet smile of success.

(Source: Modesto Bee Aug 10,1962.)

(Source: Village Newspaper (NY) 23 Aug 1962.)

"The Tiger" (student newspaper), SEP 18 1962, Vol. LXVI. No. I

Colorado College, Colorado Springs, Colorado,

……………….

Symposium Will Enable CC To Examine Spirit of Art

By Bruce Colvin

In the view of the public, modern art may well be the most puzzhng aspect of the contemporary ails. Certainly no other art form today has been the subject of so many controversies, controversies that center in the body of the general citizem-y. Through the catalyst formed by such men as a

philosopher esthetician, an art critic a social anthropologist and an experimenting scientist, Symposium will enable Colorado College to examine the spirit …Auger studied mechanical engineering at Georgia Tech for two years, and during the time became the founding editor for its literary magazine. He transferred to Columbia University to pursue his growing interest in psychology.

Auger supported himself while at Columbia as a draftsman, and went on as a research engineer-designer after his final year there.[Artificial Nerve]

A course in neurological psychology started him on an experiment in constructing artificial nerve networks capable of controlling a simulated musculature system. The device developed, from its inception in 1955 into a machine capable of performing a variety of tasks, of which painting was the final phase. When it was discovered that many of the paintings held qualities of generally accepted aesthetic values, attempts were made to increase the "free will" of the machine so that the device's creative capabilities were emphasized. The machine, its creator, and its creations have been featured in newspaper articles in the United States and Europe, and on five national television programs.

Auger was Technical Editor of the Automatic Control series from 1956 to 1960, when his book, The Relay Guide, was published. Upon

forms of ^^^ publication of the book(?) Auger made an extensive trip abroad which took him through the USSR, where he gained an interest in research being done in the fluid amplification field, a field in which he has now achieved prominence in America. Raymond Auger will be an extremely interesting participant in the Symposium, and his machine, which he will demonstrate, may raise important questions as to the true definition of art.…………

Probably the most thought provoking segment of this year's Symposium will be presented by a young scientist, Raymond Auger.

Through his interest in the field of automatic control, Auger has developed a machine which can be programmed to create paintings.……………

The ideas of art critic Clement Greenberg were discussed by Dr. Amest of the art department. He emphasized that Greenberg can speak on many aspects of contemporary life in addition to the visual arts. Less was said about the ideas of Raymond Auger, the designer of the painting machine, but a full account of his scientific and literary background was given.

…………….

1:30 p.m. Demonstration ond Talk by Raymond AugerFine Arts Center

"Programmed Art" (Painting Machine) Discussion

Presiding: Mary Chenoweth. Art Department

Discussant: Michael Phillips. Art Department………….

Raymond AugerMachine Duplicates Artistic Creativity

The history of Raymond Auger and his painting machine is a fascinating story of development and experiment. The machine began with Auger's first interest in neuron analogies, artificial nerve networks, which he could use to control a musculature system comparable in many ways to biological counterparts. He thought to use the device as a substitute for human beings in various hazardous or dull occupations and developed a manipulator with the dexterity of a human arm. Work on the device began in 1955 and development was completed in 1959. During the last phases of the machine's development it was programmed to perform a variety of tasks: to play with the children's blocks, to cook simple foods, and finally to draw letters on a blackboard. When it finally was programmed to paint it was more as a test of accuracy and repeatability than as an attempt to produce art, but it was observed that much of what the machine did, largely as a result of random elements introduced into the paintings being made, had generally accepted esthetic value. When the machine's "artistic" capabilities became known, an attempt was made to increase its free will and many of it's paintings were sold at a modest price.

A short time later Mr. Auger attempted to exploit further some of the machine's work in a gallery in Greenwich Village where it attracted a good deal of attention and interest, however the profit involved was not sufficient to justify the machine's time, so it was returned to the laboratory.

Raymond Auger is a young man, born in 1929, and a graduate of Columbia University, where he first majored in psychology and then reverted to mechanical engineering. He has travelled extensively in the Soviet Union and has written a book, The Relay Guide, published in 1960. He was Assistant Editor of the magazine Control Engineer between 1954 and 1956 and during the years 1956-60 was technical editor of Automatic Control Magazine.

…………

Raymond Auger, a Program Systems Engineer and inventor of the Painting Machine," which he will demonstrate;

What Next? Artist With a Screw Loose

By STUART PRESTON

1962. New York Times News Service NEW YORK. —

"Take Home a Machine-Made Painting While U Want It" reads the agressive sign over the door of the "Automatic Art Show" in a little shop at 110 Macdougal St.

The plea, not to be resisted, has been drawing amused and interested crowds these summer evenings.

Has the machine stepped on to the art stage, hitherto the arena of human beings? The news is grave.ONCE INDOORS we confront the machine itself, an anything but efficient – looking contraption of wires and electronic gadgets in apparently hopeless tangle, whose mysterious workings are presided over by its inventor Raymond Auger, a mild and beaded young Frankenstein.

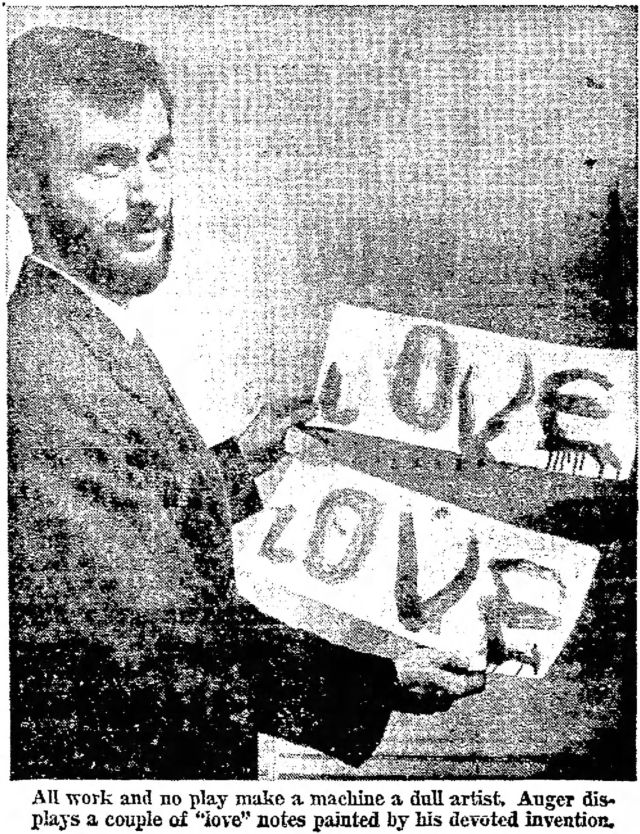

Displayed on the walls are its most recent inner-directed action paintings, some making passes at the human figure.

Others spell out words, as lucid as love, or sequences like mene, mene, tek —?

The machine is easier to describe than to comprehend. Briefly, its actions, like those of a pianola, are dictated by a heavily punctured roll of thickened paper running through its "brain."

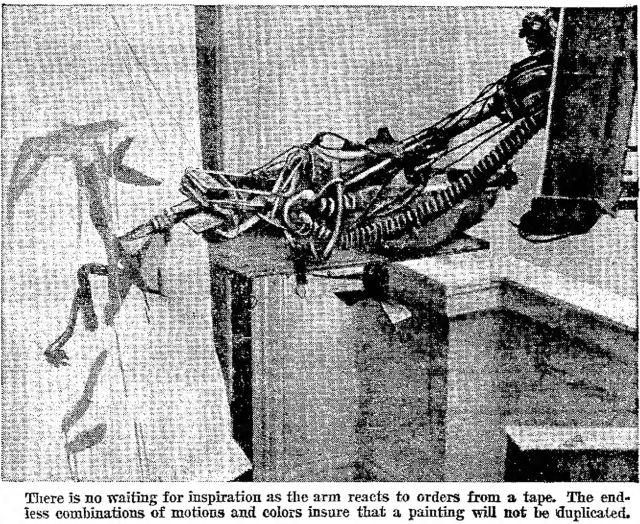

ATTACHED IS an armature ending in a viscious – looking clam, which opens and shuts its mouth like an alligator, grabs the brushes, dips them in four paint pots containing black, red, blue and yellow, and revolves on a rotating stand. Thus armed it attacks the canvas when Auger turns on the switch.

The moving finger writes, and then moves on.

To set all this in motion involves taking an old-fashioned and perfectly comprehensible step— the handing over of the sum of $2, not inserted in the machine but placed in Auger's palm, a relievingly humanistic gesture in this brave new world, Then the crowd of onlookers goes wild as the wheels begin to stir and the brush to wave.PRESUMABLY, since each sequence of action follows the master mind of the roll, playing it twice over should produce identical results. This is not at all the case. The machine behaves highly temperamentally, at one time full of zest, at others listless and even sulky.

Today it behaved in a distinctly hostile manner, swinging round from the canvas to lunge at spectators. It took forcible manual means to get it back on the job, even to the extent of pushing the canvas forward to overcome its bashfulness. Once there it developed an aversion to the pot of red paint and performed languorously, creating on the canvas in less than five minutes no more than an arty Japanese dry-brush composition. Such moods are unpredictable.THIS IS THE only machine of its kind constructed by Auger and, as such, reflects credit on his inventive and engineering ability as well as on his loyalty to the spirit of Dada in composing pictures according to the unpredictable and irrational laws of chance.

But he has had one forerunner in this field, the French artist Jean Tinguely, whose painting machine of a few years ago earned notoriety in Paris, and later in New York when demonstrate at the Staempfli Gallery.

Off Washington Square by Jane Kramer 1963

THE GROANING GEARS THAT MAKE AN ARTIST

RAYMOND AUGER HAS PACKED UP HIS PAINTING machine and left the Village [Greenwich Village, N.Y.]. The young engineer who teamed up with a shy and gangly robot and for two newsworthy weeks turned out abstract paintings in a perfume shop on MacDougal Street feels that the world is not quite ready for automatic art. He is going back to making automatic brains. The world, he says, is ready for them.

When he talked to me last week, Auger was already on his way. He looked wistfully down at his robot, which was groaning in an attempt to locate the yellow paint pot. "Humidity's got it down. Its axis is sluggish," he said. He looked sadly up at the more recent paintings on the wall—slash-school abstracts in red, yellow, blue, and black. "Not its best work at all. Besides, it frightens Frenchy. We're going home."

Frenchy, a plainly hip gentleman in blue jeans who represented the landlady in guarding the perfume from the robot, came out of the back room, where he had been hopefully playing taps on the harmonica. He glared at the robot, which swung its one arm around at him.

"This thing, this monster! It gives me nightmares. They're always the same.. .. I'm reaching for the J & B when all of a sudden this arm shoots out and grabs the bottle. . . . Then I wake up."

"Philistine," Auger said.

The machine, meanwhile, having given up on yellow, was cranking out a study in red, black, and blue. "I didn't mean to make this thing," Auger apologized. "I was actually working on an industrial control system when it happened. I had programmed the manipulator to form letters, and the damn thing began to paint instead.

"Of course I don't take it seriously. How could I? It would be like taking the Village seriously." Auger had just been to his first Village party. There had been Benzedrine in the punch. "It would be like taking that seriously," he said.

The people who crowd the store to see the robot are the ones who do. Auger insists that one customer stormed out when another asked that the machine stop using so much black. "I can't stay here and watch anyone dictate to an artist," the man had said.

"What a comment on the times," Auger said. "A machine designed to be a staid executive instrument turns, as a diversion, to painting—like a Churchill or a Gauguin—and I, an engineer, turn to art criticism to keep up with it."

By the time Auger finished philosophizing, the machine had managed to crank the moisture out of its controls. Its wheels began to chug without squeaking, and its long arm of coils and clamps and wires writhed around and dipped into the black paint pot. Auger peered over the slowly rotating electronic tape on which its "principles" are punched in the manner of a Time subscription blank. "There it goes," he shouted as the arm lifted a brush to the easel and ejected a black triangle from a clamp that opened and shut like a yawning dinosaur.

"My God!" said Auger, jumping up as the robot planted a dripping red arc on the paper. "There's nothing in the program for a red arc." For a moment it looked as though his robot had come to more creative life than either of them had planned. But eventually Auger admitted to a source of error in the tape. He donned a white laboratory coat over his black corduroy jacket for the investigation. The perfume shop took on, with Auger's coat, some of the more lugubrious aspects of the old lab set for Late Late Shows.

In the middle of the room stood the machine, its clamp-hand suspended over the red paint pot. A small, nervous Auger was poring over the tape, stroking his long red beard. Frenchy was glowering in the background; Gothic sounds issued from Frenchy's harmonica. A stranger who had stopped at the door was staring in, his mouth hanging open. And the dishwasher from the Cafe Bizarre was pacing the floor. "I want to be a waiter, I want to be a waiter," he kept saying to himself.

Auger sat down and tried to explain the whole thing.

From its main taped memory, it seems, the machine actually makes the decisions as to how to move its brushes on the paper. "It shows that element of unpredictability common to all creative processes and in one way proves the relation between artistic style and causal factors," Auger said. The machine is deliberately invested with independence. Programmed toward three capacities—to choose its colors at random, to choose its own symbols from its main memory, and to vary the probability of its artistic choices—it can paint any number of variations on any one given set of data. Its taped memory is roughly equivalent to the causal factor in human skills. "Frightening, isn't it?" Auger said.

Given the time and money, Auger is convinced that he can turn out Rembrandts, too. He is Columbia-trained and, at thirty-two, the author of a technical book, the editor of a scientific journal, and the president of two corporations. He appears sane.

He was about to turn off the painting—"You had better take it the way it is now, or there's no telling how messy it will get"—when his secretary, a big blonde in a burlap tunic, wriggled in. "She needed a home," Auger explained. "I always let my secretaries live in. I take them in with the best instincts. This one's new."

He turned to the blonde. "Why the hell did you buy jelly doughnuts with all the grocery money?"

"You geniuses are so touchy," was all that the blonde said.

"Make sure you don't call it a robot—it's a program manipulator," Auger called out as he turned off the artist, grabbed his housekeeper, and left for home.

Fluidic Amplifier

In 1962, Ray Auger discovered a fluidic logic element called "Turbulence Amplifier".

The term fluidics relates to the combination of the two functions namely fluid amplification and fluid logic.

Fluidics is defined as a control technology which makes use of fluids interaction to produce useful signals.

• The "field of fluidics" is the study of the performance and response characteristics of control systems, computing devices and logical switch gears based on the

fluidic elements.

• In finer control engineering, non-moving logic elements find a prominent place.

Irrespective of the development of electronics, low pressure pneumatic and fluidic elements have certain specific characteristics which put them at par with electronic controls even for modern sophisticated machines. Various fluidic elements have been developed conforming to the need of logic functions in the industrial automation.

— The basic principle is derived from the "Tesla's fluid-diode" and theory of "wall attachment" discovered by Coanda

— More and more fluid-logic elements in the form of logic gates like OR, NOR, etc. are being used along with power pneumatic circuits to offer better control and feedback to the pneumatic system. One of the major areas of their application is in the field of sensors. The present day state of art of pneumatic sensors is quite competitive with other form of sensors e.g., fine mechanical, opto-electrical, inductive, hydraulic, ultra sound and magnetic devices etc. and are therefore widely used in various engineering tools and instruments.

Publication number US3234955 A

Publication date Feb 15, 1966

Filing date Oct 1, 1962

Inventors Auger Raymond N

Original Assignee Auger Raymond N

See all the Art Robots and Painting Machines here.

Raymond taught me how to put together the parts for his turbulence amplifier in early 1962. Is he still alive?

Super interesting!!