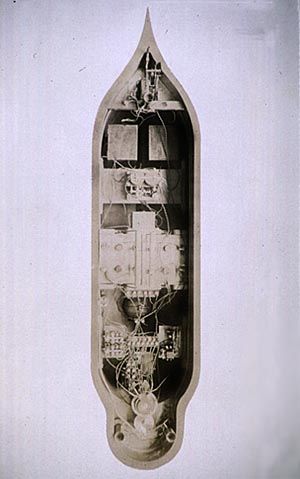

Model

Model

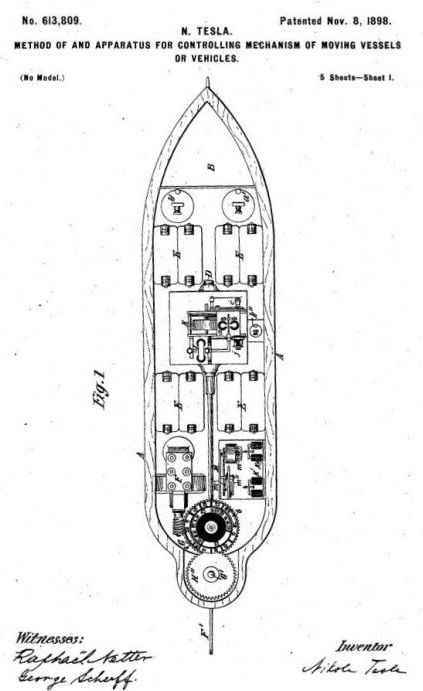

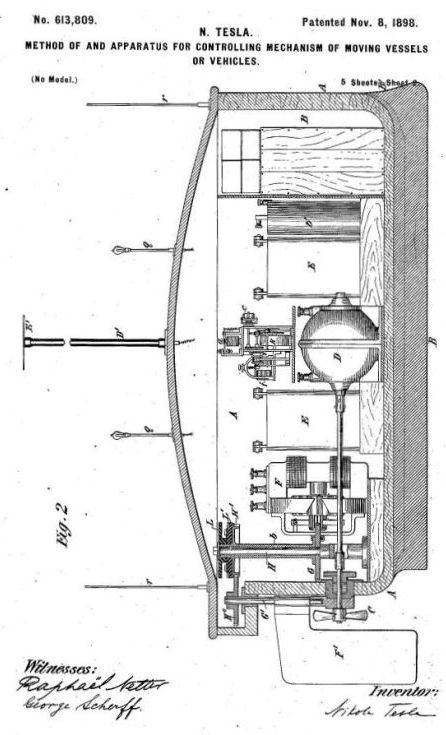

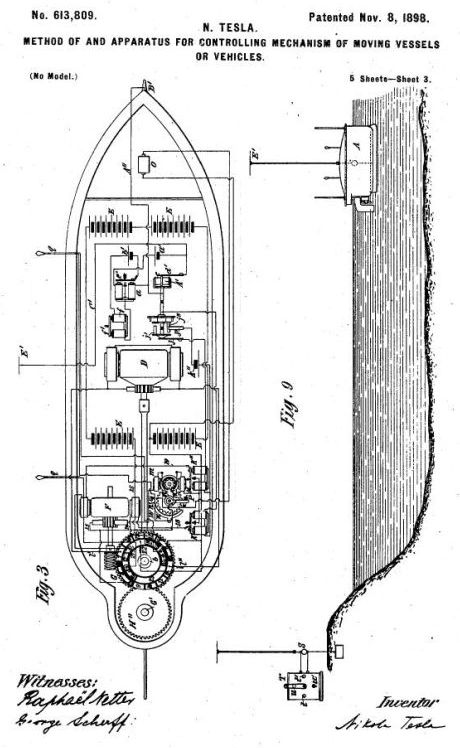

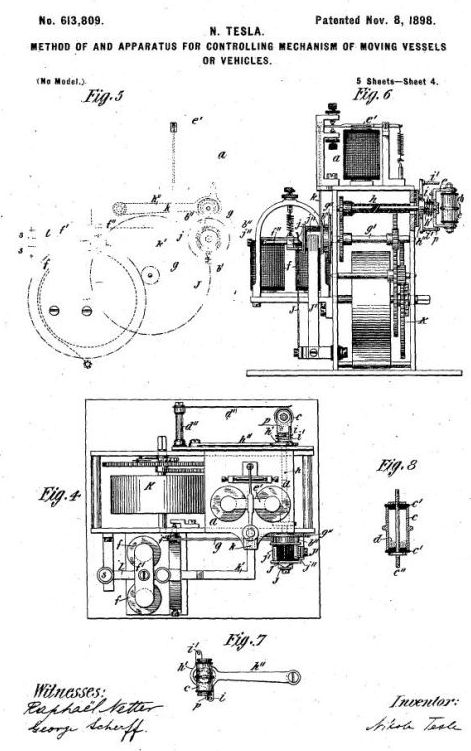

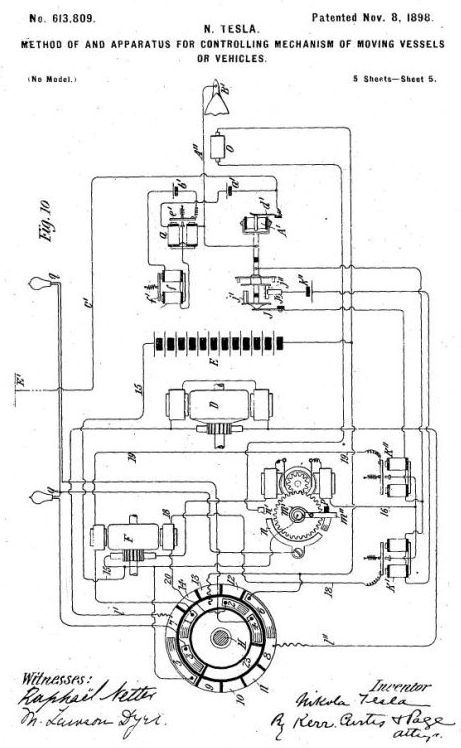

Patent number: 613809 (see full patent here)

Filing date: Jul 1, 1898

Issue date: Nov 1898

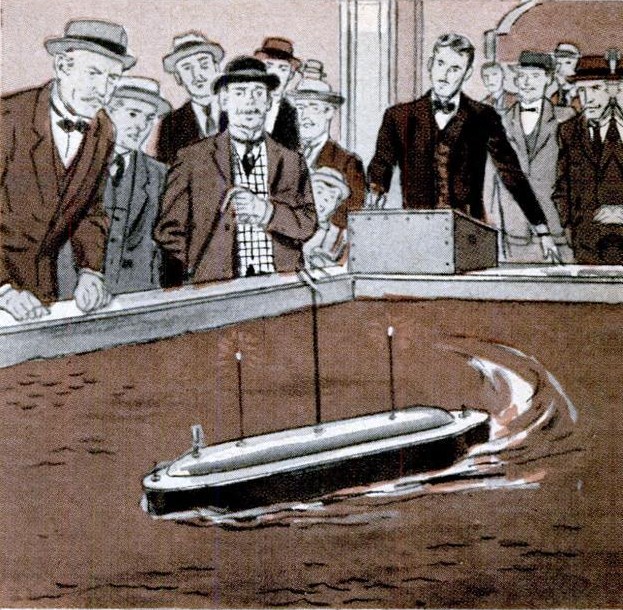

In September 1898, Tesla demonstrates his radio-controlled torpedo boat at Madison Square Garden in Ney York City. (Popular Science July 1956).

From Miessner's book "On the Early History of Radio Guidance", published in 1964.

44 BENJAMIN FRANKLIN MIESSNER……

I [Miessner] am almost certain that the reader who reviewed the book for Van Nostrand was none other than Nikola Tesla. Since I was planning to include descriptions and drawings of his pioneering efforts in the field of automatic control, I had written to him, only to find that he was already well acquainted with my project. We exchanged three letters in all, the first in September 1915. (The originals of his letters are in the Manuscript Division of the New York Public Library.)

Tesla to Miessner, Sept. 29, 1915:

Your favor of September 24th has been received in due course and has interested me in view of your forthcoming book on "Radio Dynamics". Some time ago my friend, Charles E. Speirs of the D. Van Nostrand Company, told me that you were engaged in its preparation and I commended it for publication as very little has been written on the subject …

I am naturally greatly absorbed in this field of invention which has been barely touched and which I look upon as extremely promising. In an article in the Century Magazine, copy of which I am forwarding to you, I have related the circumstances which led me to develop the idea of a self-propelled automaton. My experiments were begun sometime in '92 and from that period, on, until '95, in my Laboratory at 35 South Fifth Avenue, I exhibited a number of contrivances and perfected plans for several complete telautomata. After the destruction of my Laboratory by fire in '95, there was an interruption in these labors which, however, were resumed in '96 in my new Laboratory at 46 East Houston Street where I made more striking demonstrations,

44 BENJAMIN FRANKLIN MIESSNER

in many instances actually transmitting the whole motive energy to the devices instead of simply controlling the same from distance. In '97 I began the construction of a complete automaton in the form of a boat, which is described in my original patent specification 013,809. A copy of this, also, is being forwarded under separate cover. This application was written during that year but the filing was delayed until July of the following year, long before which date the machine had been often exhibited to visitors who never ceased to wonder at the performances. The drawings of this specification were made from this machine to scale. In that year I also constructed a larger boat which I exhibited, among other things, in Chicago during a lecture before the Commercial Club. In this lecture I treated the whole field broadly, not limiting myself to mechanisms controlled from distance but to machines possessed of their own intelligence. Since that time I have advanced greatly in the evolution of the invention and think that the time is not distant when I shall show an automaton which, left to itself, will act as though possessed of reason and without any wilful control from the outside. Whatever be the practical possibilities of such an achievement, it will mark the beginning of a new epoch in mechanics.

I would call your attention to the fact that while my specification, above mentioned, shows the automatic mechanism as controlled through a simple tuned circuit, I have used individualized control; that is, one based on the co-operation of several circuits of different periods of vibration, a principle which I had already developed at that time and which was subsequently described in my patents #723,188 and 723,189 of March, 1903. The machine was in this form when I made demonstrations with it in 1898 before the Chief Examiner, Seeley, prior to the grant of my basic patent on Method of and Apparatus for Controlling Mechanisms at a Distance. [My italics.]

In my experiments and investigations in Colorado from 1899 to 1900, I developed, among other things, two important discoveries which will be essential in the future development of telautomatics. They are described in my patents #685,953 and 119,732 which were taken out at a later date. These two advances make it possible to supply to an automaton great amounts of energy and also to control it with the utmost accuracy when it is entirely out of sight and at any distance.

THE PROBLEM OF INCREASING HUMAN ENERGY

WITH SPECIAL REFERENCES TO THE HARNESSING OF THE SUN'S ENERGY.

by Nikola Tesla

Century Illustrated Magazine, June 1900

THE ONWARD MOVEMENT OF MAN—THE ENERGY OF THE MOVEMENT—THE THREE WAYS OF INCREASING HUMAN ENERGY.

…….

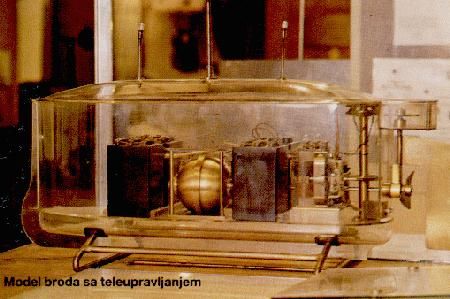

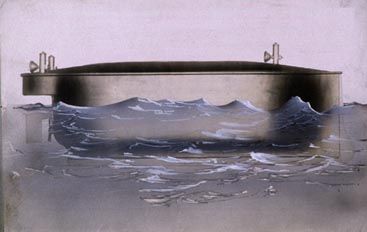

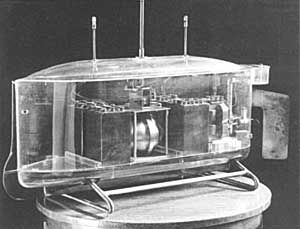

Figure 2.

A machine having all the bodily or translatory movements and the operations of the interior mechanism controlled from a distance without wires. The crewless boat shown in the photograph contains its own motive power, propelling and steering machinery, and numerous other accessories, all of which are controlled by transmitting from a distance, without wires, electrical oscillations to a circuit carried by the boat and adjusted to respond only to these oscillations.With these experiences it was only natural that, long ago, I conceived the idea of constructing an automaton which would mechanically represent me, and which would respond, as I do myself, but, of course, in a much more primitive manner, to external influences. Such an automaton evidently had to have motive power, organs for locomotion, directive organs, and one or more sensitive organs so adapted as to be excited by external stimuli. This machine would, I reasoned, perform its movements in the manner of a living being, for it would have all the chief mechanical characteristics or elements of the same. There was still the capacity for growth, propagation, and, above all, the mind which would be wanting to make the model complete. But growth was not necessary in this case, since a machine could be manufactured full grown, so to speak. As to the capacity for propagation, it could likewise be left out of consideration, for in the mechanical model it merely signified a process of manufacture. Whether the automation be of flesh and bone, or of wood and steel, it mattered little, provided it could perform all the duties required of it like an intelligent being. To do so, it had to have an element corresponding to the mind, which would effect the control of all its movements and operations, and cause it to act, in any unforeseen case that might present itself, with knowledge, reason, judgment, and experience. But this element I could easily embody in it by conveying to it my own intelligence, my own understanding. So this invention was evolved, and so a new art came into existence, for which the name "telautomatics" has been suggested, which means the art of controlling the movements and operations of distant automatons. This principle evidently was applicable to any kind of machine that moves on land or in the water or in the air. In applying it practically for the first time, I selected a boat (see Fig. 2). A storage battery placed within it furnished the motive power. The propeller, driven by a motor, represented the locomotive organs. The rudder, controlled by another motor likewise driven by the battery, took the place of the directive organs. As to the sensitive organ, obviously the first thought was to utilize a device responsive to rays of light, like a selenium cell, to represent the human eye. But upon closer inquiry I found that, owing to experimental and other difficulties, no thoroughly satisfactory control of the automaton could be effected by light, radiant heat, hertzian radiations, or by rays in general, that is, disturbances which pass in straight lines through space. One of the reasons was that any obstacle coming between the operator and the distant automaton would place it beyond his control. Another reason was that the sensitive device representing the eye would have to be in a definite position with respect to the distant controlling apparatus, and this necessity would impose great limitations in the control. Still another and very important reason was that, in using rays, it would be difficult, if not impossible, to give to the automaton individual features or characteristics distinguishing it from other machines of this kind. Evidently the automaton should respond only to an individual call, as a person responds to a name. Such considerations led me to conclude that the sensitive device of the machine should correspond to the ear rather than the eye of a human being, for in this case its actions could be controlled irrespective of intervening obstacles, regardless of its position relative to the distant controlling apparatus, and, last, but not least, it would remain deaf and unresponsive, like a faithful servant, to all calls but that of its master. These requirements made it imperative to use, in the control of the automaton, instead of light or other rays, waves or disturbances which propagate in all directions through space, like sound, or which follow a path of least resistance, however curved. I attained the result aimed at by means of an electric circuit placed within the boat, and adjusted, or "tuned," exactly to electrical vibrations of the proper kind transmitted to it from a distant "electrical oscillator." This circuit, in responding, however feebly, to the transmitted vibrations, affected magnets and other contrivances, through the medium of which were controlled the movements of the propeller and rudder, and also the operations of numerous other appliances.

By the simple means described the knowledge, experience, judgment—the mind, so to speak—of the distant operator were embodied in that machine, which was thus enabled to move and to perform all its operations with reason and intelligence. It behaved just like a blindfolded person obeying directions received through the ear.

The automatons so far constructed had "borrowed minds," so to speak, as each merely formed part of the distant operator who conveyed to it his intelligent orders; but this art is only in the beginning. I purpose to show that, however impossible it may now seem, an automaton may be contrived which will have its "own mind," and by this I mean that it will be able, independent of any operator, left entirely to itself, to perform, in response to external influences affecting its sensitive organs, a great variety of acts and operations as if it had intelligence. It will be able to follow a course laid out or to obey orders given far in advance; it will be capable of distinguishing between what it ought and what it ought not to do, and of making experiences or, otherwise stated, of recording impressions which will definitely affect its subsequent actions. In fact, I have already conceived such a plan.

Although I evolved this invention many years ago and explained it to my visitors very frequently in my laboratory demonstrations, it was not until much later, long after I had perfected it, that it became known, when, naturally enough, it gave rise to much discussion and to sensational reports. But the true significance of this new art was not grasped by the majority, nor was the great force of the underlying principle recognized. As nearly as I could judge from the numerous comments which appeared, the results I had obtained were considered as entirely impossible. Even the few who were disposed to admit the practicability of the invention saw in it merely an automobile torpedo, which was to be used for the purpose of blowing up battleships, with doubtful success. The general impression was that I contemplated simply the steering of such a vessel by means of Hertzian or other rays. There are torpedoes steered electrically by wires, and there are means of communicating without wires, and the above was, of course an obvious inference. Had I accomplished nothing more than this, I should have made a small advance indeed. But the art I have evolved does not contemplate merely the change of direction of a moving vessel; it affords means of absolutely controlling, in every respect, all the innumerable translatory movements, as well as the operations of all the internal organs, no matter how many, of an individualized automaton. Criticisms to the effect that the control of the automaton could be interfered with were made by people who do not even dream of the wonderful results which can be accomplished by use of electrical vibrations. The world moves slowly, and new truths are difficult to see. Certainly, by the use of this principle, an arm for attack as well as defense may be provided, of a destructiveness all the greater as the principle is applicable to submarine and aerial vessels. There is virtually no restriction as to the amount of explosive it can carry, or as to the distance at which it can strike, and failure is almost impossible. But the force of this new principle does not wholly reside in its destructiveness. Its advent introduces into warfare an element which never existed before—a fighting-machine without men as a means of attack and defense. The continuous development in this direction must ultimately make war a mere contest of machines without men and without loss of life—a condition which would have been impossible without this new departure, and which, in my opinion, must be reached as preliminary to permanent peace. The future will either bear out or disprove these views. My ideas on this subject have been put forth with deep conviction, but in a humble spirit.

Nikola Tesla – Prodigal Genius by John J. O'Neill

Nikola Tesla – Prodigal Genius

p164

TESLA developed his inventions to the point at which they were spectacular performers before they were demonstrated to the public. When presented, the performance always greatly exceded the promise. This was the case with his first public demonstration of "wireless," but he complicated the situation by coupling with his radio invention another new idea—the robot (see my note below-RH).

Tesla staged his demonstration in the great auditorium of Madison Square Garden, then on the north side of Madison Square, in September, 1898, as part of the first annual Electrical Exhibition. He had a large tank built in the center of the arena

165

and in this he placed an iron-hulled boat a few feet long, shaped like an ark, which he operated by remote control by means of his wireless system.

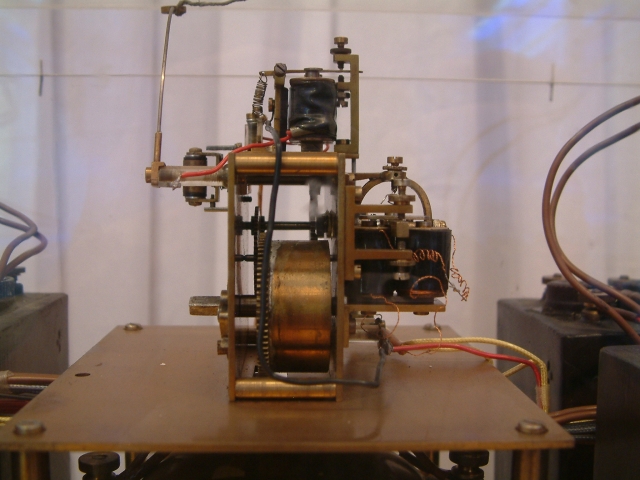

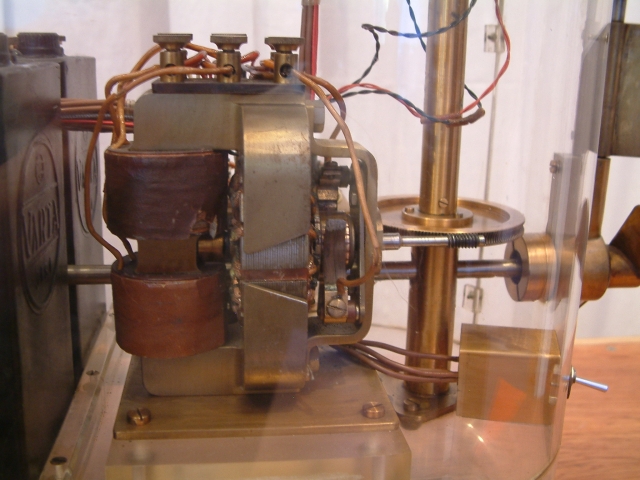

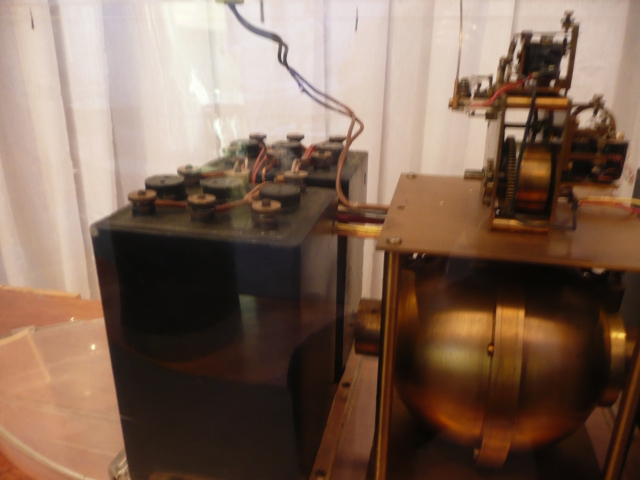

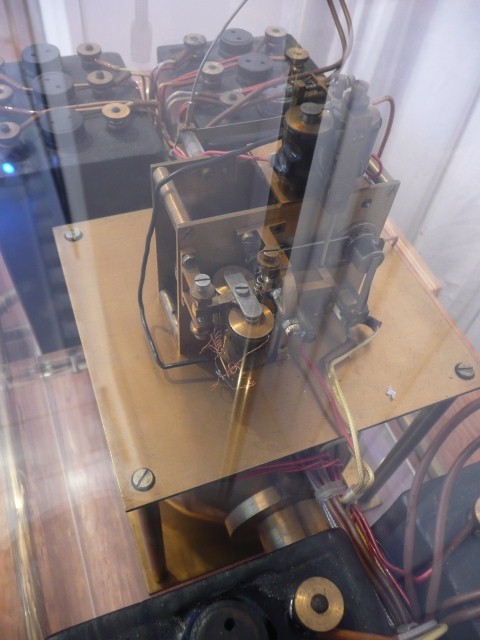

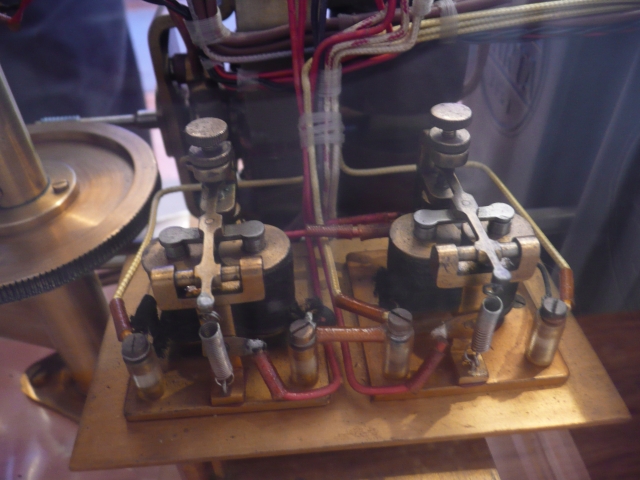

Extending upward from the center of the roof of the boat was a slender metal rod a few feet high which served as an antenna, or aerial, for receiving the wireless wave. Near the bow and stern were two small metal tubes about a foot high surmounted by small electric lamps. The interior of the hull was packed with a radio receiving set and a variety of motor-driven mechanisms which put into effect the operating orders sent to the boat by wireless waves. There was a motor for propelling the boat and another motor for operating the servo-mechanism, or mechanical brain, that interpreted the orders coming from the wireless receiving set and translated them into mechanical motions, which included steering the boat in any direction, making it stop, start, go forward or backward, or light either lamp. The boat could thus be put through the most complicated maneuvers.

Anyone attending the exhibition could call the maneuver for the boat, and Tesla, with a few touches on a telegraph key, would cause the boat to respond. His control point was at the far end of the great arena.

The demonstration created a sensation and Tesla again was the popular hero. It was a front-page story in the newspapers. Everyone knew the accomplishment was a wonderful one, but few grasped the significance of the event or the importance of the fundamental discovery which it demonstrated. The basic aspects of the invention were obscured by the glamor of the demonstration.

The Spanish American War was under way. The success of the U.S. Navy in destroying the Spanish fleets was the leading topic of conversation. There was resentment over the blowing up of the U.S.S. Maine in Havana Harbor. Tesla's demonstration fired the imagination of everyone because of its possibilities as a weapon in naval warfare.

166

Waldemar Kaempffert, then a student in City College and now Science Editor of the New York Times, discussed its use as a weapon with Tesla.

"I see," said Kaempffert, "how you could load an even larger boat with a cargo of dynamite, cause it to ride submerged, and explode the dynamite whenever you wished by pressing the key just as easily as you can cause the light on the bow to shine, and blow up from a distance by wireless even the largest of battleships." (Edison had earlier designed an electric torpedo which received its power by a cable that remained connected with the mother ship.)

Tesla was patriotic, and was proud of his status, which he had acquired in 1889, as a citizen of the United States. He had offered his invention to the Government as a naval weapon, but at heart he was opposed to war.

"You do not see there a wireless torpedo," snapped back Tesla with fire flashing in his eyes, "you see there the first of a race of robots, mechanical men which will do the laborious work of the human race."

The "race of robots" was another of Tesla's original and im-portant contributions to human welfare. It was one of the items of this colossal project for increasing human energy and improving the efficiency of its utilization. He visualized the application of the robot idea to warfare as well as to peaceful pursuits; and out of the broad principles enunciated, lie developed an accurate picture of warfare as it is being carried on today with the use of giant machines as weapons—the robots he described.

"This evolution," he stated in an article in the Century Magazine of June, 1900, "will bring more and more into prominence a machine or mechanism with the fewest individuals as an element of warfare. . . . Greatest possible speed and maximum ale of energy delivery by the war apparatus will be the main object. The loss of life will become smaller. . . ."

Outlining the experiences that led him to design the robots, or automatons, as he called them, Tesla stated:

167

I have by every thought and act of mine, demonstrated, and do so daily, to my absolute satisfaction that I am an automaton endowed with power of movement, which merely responds to external stimuli beating upon my sense organs, and thinks and moves accordingly. . . .

With these experiences it was only natural that, long ago, I conceived the idea of constructing an automaton which would mechanically represent me, and which would respond, as I do myself, but, of course, in a much more primitive manner, to external influences. Such an automaton evidently had to have motive power, organs for locomotion, directive organs, and one or more sensitive organs so adapted as to be excited by external stimuli.

This machine would, I reasoned, perform its movements in the manner of a living being, for it would have all of the chief elements of the same. There was still the capacity for growth, propagation, and, above all, the mind which would be wanting to make the model complete. But growth was not necessary in this case since a machine could be manufactured full-grown, so to speak. As to capacity for propagation, it could likewise be left out of consideration, for in the mechanical model it merely signified a process of manufacture.

Whether the automaton be of flesh and bone, or of wood and steel, mattered little, provided it could perform all the duties required of it like an intelligent being. To do so it would have to have an element corresponding to the mind, which would effect the control of its movements and operations, and cause it to act, in any unforeseen case that might present itself, with knowledge, reason, judgement and experience. But this element I could easily embody in it by conveying to it my own intelligence, my own understanding. So this invention was evolved, and so a new art came into existence, for which the name "telautomatics" has been suggested, which means the art of controlling the movements and operations of distant automatons.

In order to give the automaton an individual identity it would be provided with a particular electrical tuning, Tesla explained, to which it alone would respond when waves of that particular frequency were sent from a control transmitting station; and other automatons would remain inactive until their frequency was transmitted. This was Tesla's fundamental radio tuning invention, the need for which other radio inventors had not yet

168

glimpsed although Tesla had described it publicly a half-dozen years earlier.

Tesla not only used in the control of his automaton the long waves now used in broadcasting—which are very different from the short waves used by Marconi and all others; for those could be interfered with by the imposition of an intervening object— but he was explaining the use, through his system of tuning, of the spectrum of allocations for individual stations that now appears on the dials of radio receiving sets. He continued:

By the simple means described the knowledge, experience, judgement—the mind, so to speak—of the distant operator were embodied in that machine, which was thus enabled to move and perform all of its operations with reason and intelligence. It behaved just like a blindfolded person obeying directions received through the ear.

The automatons so far constructed had "borrowed minds," so to speak, as each formed merely part of the distant operator who conveyed to it his intelligent orders; but this art is only in the beginning.

I purpose to show that, however impossible it may now seem, an Automaton may be contrived which will have its "own mind," and by this I mean that it will be able, independently of any operator, kit entirely to itself, to perform, in response to external influences affecting its sensitive organs, a great variety of acts and operations as if it had intelligence.

It will be able to follow a course laid out or to obey orders given far in advance; it will be capable of distinguishing between what it might and ought not to do, and of making experiences or, otherwise stated, of recording impressions which will definitely affect its subsequent actions. In fact I have already conceived such a plan.

Although I evolved this invention many years ago and explained it to my visitors very frequently in my laboratory demonstrations, it was not until much later, long after I had perfected it, that it became known, when, naturally enough, it gave rise to much discussion and to sensational reports.

But the true significance of this new art was not grasped by the majority, nor was the great force of the underlying principle recognized. As nearly as I could judge from the numerous comments which then appeared, the results I had obtained were considered as entirely impossible. Even the few who were disposed to admit the

169 practicability of the invention saw in it merely an automobile torpedo, which was to be used for the purpose of blowing up battleships, with doubtful success. . . .

But the art I have evolved does not contemplate merely the change of direction of a moving vessel; it affords means of absolutely controlling in every respect, all the innumerable translatory movements, as well as the operations of all the internal organs, no matter how many, of an individualized automaton.

Tesla, in an unpublished statement, prepared fifteen years later, recorded his experience in developing automata, and his unsuccessful effort to interest the War Department, and likewise commercial concerns, in his wirelessly controlled devices.

The idea of constructing an automaton, to bear out my theory, presented itself to me early but I did not begin active work until 1893, when I started my wireless investigations. During the succeeding two or three years, a number of automatic mechanisms, actuated from a distance by wireless control, were constructed by me and exhibited to visitors in my laboratory.

In 1896, however, I designed a complete machine capable of a multitude of operations, but the consummation of my labors was delayed until later in 1897. This machine was illustrated and described in my article in the Century Magazine of June 1900, and other periodicals of that time and, when first shown in the beginning of 1898, it created a sensation such as no other invention of mine has ever produced.

In November 1898, a basic patent on the novel art was granted to me, but only after the Examiner-in-Chief had come to New York and witnessed the performance, for what I claimed seemed unbelievable. I remember that when later I called on an official in Washington, with a view of offering the invention to the Government, he burst out in laughter upon my telling him what I had accomplished. Nobody thought then that there was the faintest prospect of perfecting such a device.

It is unfortunate that in this patent, following the advice of my attorneys, I indicated the control as being effected through the medium of a single circuit and a well-known form of detector, for the reason that I had not yet secured protection on my methods and apparatus for individualization. As a matter of fact, my boats were controlled through the joint action of several circuits and inter-

170 ference of every kind was excluded. Most generally I employed receiving circuits in the form of loops, including condensers, because the discharges of my high tension transmitter ionized the air in the hall so that even a very small aerial would draw electricity from the surrounding atmosphere for hours.

Just to give an idea, I found, for instance, that a bulb 12" in diameter, highly exhausted, and with one single terminal to which a short wire was attached, would deliver well on to one thousand successive flashes before all charge of the air in the laboratory was neutralized. The loop form of receiver was not sensitive to such a disturbance and it is curious to note that it is becoming popular at this late date. In reality it collects much less energy than the aerials or a long grounded wire, but it so happens that it does away with a number of defects inherent to the present wireless devices.

In demonstrating my invention before audiences, the visitors were requested to ask any questions, however involved, and the automaton would answer them by signs. This was considered magic at that time but was extremely simple, for it was myself who gave the replies by means of the device.

At the same period another larger telautomatic boat was constructed. It was controlled by loops having several turns placed in the hull, which was made entirely water tight and capable of submergence. The apparatus was similar to that used in the first with the exception of certain special features I introduced as, for example, incandescent lamps which afforded a visible evidence of the proper functioning of the machine and served for other purposes.

These automata, controlled within the range of vision of the operator, were, however, the first and rather crude steps in the evolution of the Art of Telautomatics as I had conceived it. The next logical improvement was its application to automatic mechanisms beyond the limits of vision and at great distances from the center of control, and I have ever since advocated their employments as instruments of warfare in preference to guns. The importance of his now seems to be recognized, if I am to judge from casual announcements through the press of achievements which are said to be extraordinary but contain no merit of novelty whatever.

In an imperfect manner it is practicable, with the existing wireless plants, to launch an aeroplane, have it follow a certain approximate course, and perform some operation at a distance of many hundreds of miles. A machine of this kind can also be mechanically controlled in several ways and I have no doubt that it may prove

171 of some usefulness in war. But there are, to my best knowledge, no instrumentalities in existence today with which such an object could be accomplished in a precise manner. I have devoted years of study to this matter and have evolved means, making such and greater wonders easily realizable.

As stated on a previous occasion, when I was a student at college I conceived a flying machine quite unlike the present ones. The underlying principle was sound but could not be carried into practice for want of a prime-mover of sufficiently great activity. In recent years I have successfully solved this problem and am now planning aerial machines devoid of sustaining planes, ailerons, propellers and other external attachments, which will be capable of immense speeds and are very likely to furnish powerful arguments for peace in the near future. Such a machine, sustained and propelled entirely by reaction, can be controlled either mechanically or by wireless energy. By installing proper plants it will be practicable to project a missile of this kind into the air and drop it almost on the very spot designated which may be thousands of miles away. But we are not going to stop at this.

Tesla is here describing—nearly fifty years ago—the radio controlled rocket, which is still a confidential development of World War II, and the rocket bombs used by the Germans to attack England. The rocket-type airship is a secret which probably died with Tesla, unless it is contained in his papers sealed by the Government at the time of his death. This, however, is unlikely, as Tesla, in order to protect his secrets, did not commit his major inventions to paper, but depended on an almost infallible memory for their preservation.

"Telautomata," he concluded, "will be ultimately produced, capable of acting as if possessed of their own intelligence and their advent will create a revolution. As early as 1898 I proposed to representatives of a large manufacturing concern the construction and public exhibition of an automobile carriage which, left to itself, would perform a great variety of operations involving something akin to judgment. But my proposal was deemed chimerical at that time and nothing came from it."

Tesla, at the Madison Square Garden demonstration in 1898

172

which lasted for a week, presented to the world, then, two stupendous developments, either of which alone would have been too gigantic to have been satisfactorily assimilated by the public in a single presentation. Either one of the ideas dimmed the glory of the other.

This first public demonstration of wireless, the forerunner of modern radio, in the amazing stage of development to which Tesla carried it, at this early date, was too tremendous a project to be encompassed within a single dramatization. In the hands of a competent public-relations councillor, or publicity man, as he was called in those days (but the employment of one was utterly abhorrent to Tesla), this demonstration would have been limited to the wireless aspect alone, and would have included just a simple two-way sending-and-receiving set for the transmission of messages by the Morse dots and dashes. Suitably dramatized, this would have been a sufficient thrill for one show. At a subsequent show he could have brought in the tuning demonstration which would have shown the selective response of each of a series of coils, indicated by his strange-looking vacuum-tube lamps. The whole story of just the tuning of wireless circuits and stations to each other was too big for any one demonstration. An indication of its possibilities was all the public could absorb.

The robot, or automaton, idea was a new and an equally stupendous concept, the possibilities of which were not lost, however, on clever inventors; for it brought in the era of the modern labor-saving device—the mechanization of industry on a mass-production basis.

Using the Tesla principles, John Hays Hammond, Jr. developed an electric dog, on wheels, that followed him like a live pup. It was motor operated and controlled by a light beam through selenium cells placed behind lenses used for eyes. He also operated a yacht, entirely without a crew, which was sent out to sea from Boston harbor and brought back to its wharf by wireless control.

A manless airplane was developed toward the close of the

173

First World War. It rose from the ground, flew one hundred miles to a selected target, dropped its bombs, and returned to home airport, all by wireless control. It was also developed so that on a signal from a distant radio station the plane would rise into the air, choose the proper direction, fly to a city hundreds of miles away and set itself down in the airport at that city. This Tesla-type robot was developed in the plant of the Sperry Gyroscope Company, where Elmer Sperry invented a host of amazing mechanical robots controlled by gyroscopes, such as the automatic pilots for airplanes and for ships.

All of the modern control devices using electronic tubes anal electric eyes that make machines seem almost human and enable them to perform with superhuman activity, dependability, accuracy and low cost, are children of Tesla's robot, or automaton The most recent development, in personalized form, was the mechanical man, a metal human monster giant, that walked, talked, smoked a cigarette, and obeyed spoken orders, in the exhibit of the Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company at the New York World's Fair. Robots have been used, is well, to operate hydroelectric powerhouses and isolated substations of powerhouses.

In presenting this superabundance of scientific discovery in a single demonstration, Tesla was manifesting the superman in an additional role that pleased him greatly—that of the man magnificent. He would astound the world with a superlative demonstration not only of the profundity of the accomplishments of the superman, but, in addition, of the prolific nature of the mind of the man magnificent who could shower on the world a super-abundance of scientific discoveries.

174

ELEVEN

TESLA was now ready for new worlds to conquer. After pre- senting to the public his discoveries relating to wireless signaling or the transmission of intelligence, as he called it, Tesla was anxious to get busy on the power phase: his projected world-wide distribution of power by wireless methods.

Again Tesla was faced with a financial problem — or, to state the matter simply, he was broke. The $40,000 which was paid for the stock of the Nikola Tesla Company by Adams had been spent. The company had no cash on hand; but it held patents worth many millions if they had been handled in a practical way. A gift of $10,000 from John Hays Hammond, the famous mining engineer, had financed the work leading up to the Madison Square Garden wireless and robot demonstration.

175

RH-Dec 2010 – Although John J. O'Neill quotes Tesla, He's quoting him in 1898 using the word "robot" which wasn't coined until 1920 and came in active use by the late 1920's. He should have stayed with the word "automata".

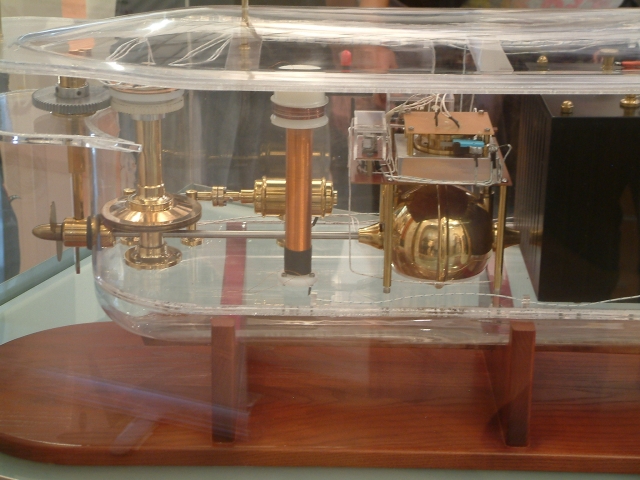

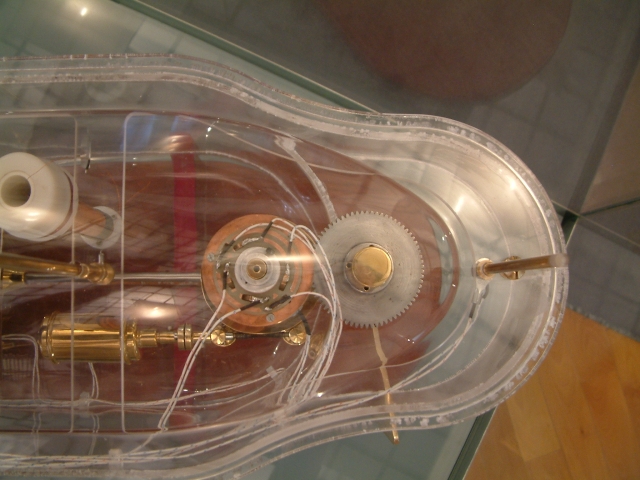

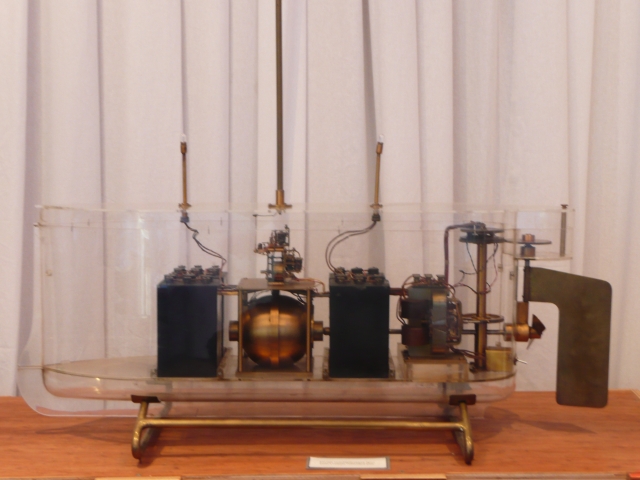

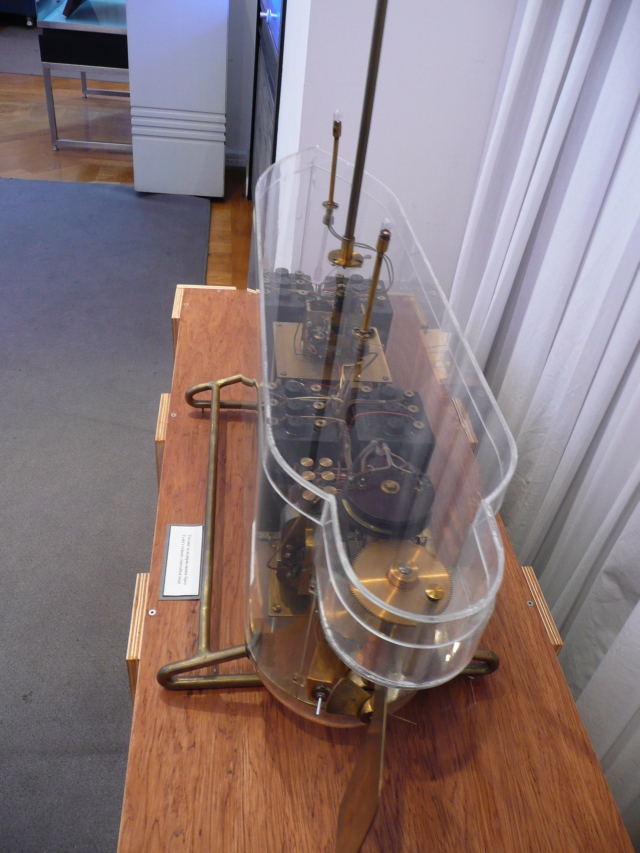

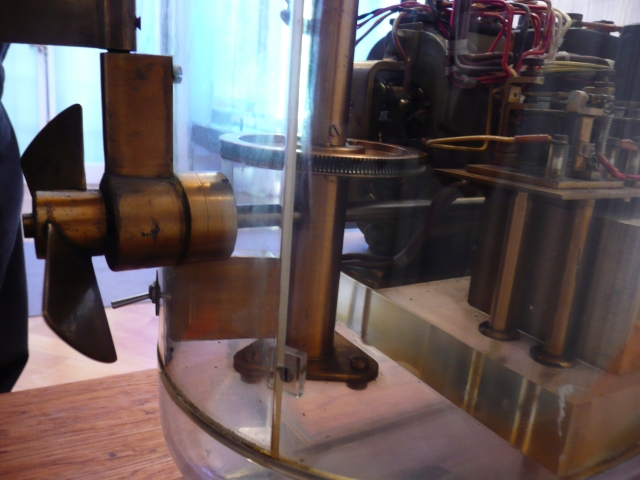

The photos below are from my European trip with David Buckley in 2009.

See the story on the above replica model here.

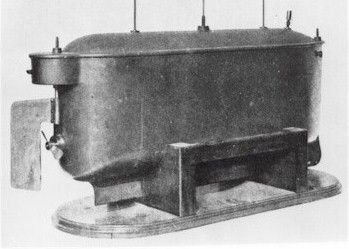

The second, older model on show at the Tesla Museum.

A replica radio-controlled robot boat, in Tesla's native village of Smiljan, some 200 kilometers south of Zagreb, on 10 July 2006. Croatia and neighboring Serbia were marking the 150th anniversary of birth of Tesla.