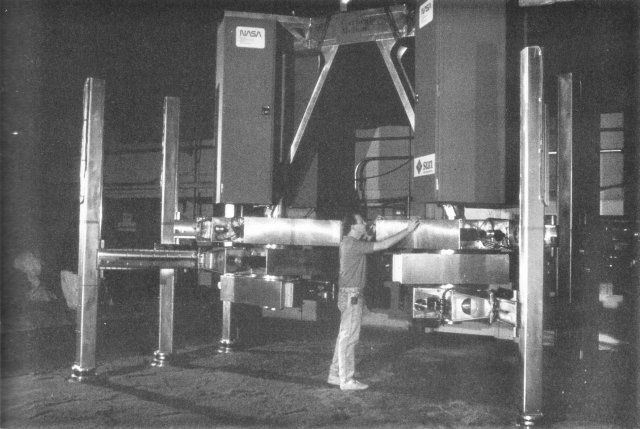

A good example of the "big iron" approach to mobile robots is AMBLER (acronym for Autonomous MoBiLe Exploration Robot), developed by Carnegie Mellon University and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. This behemoth stands about 5m (16.4ft) tall, is up to 7m (23.0ft) wide, and weights 2500 kg (5512 lb). It moves at a blistering 35 cm (13.8 in) per minute. Just sitting still, it consumes 1400 W of power. Ask it to walk and it sucks up just about 4000 W.

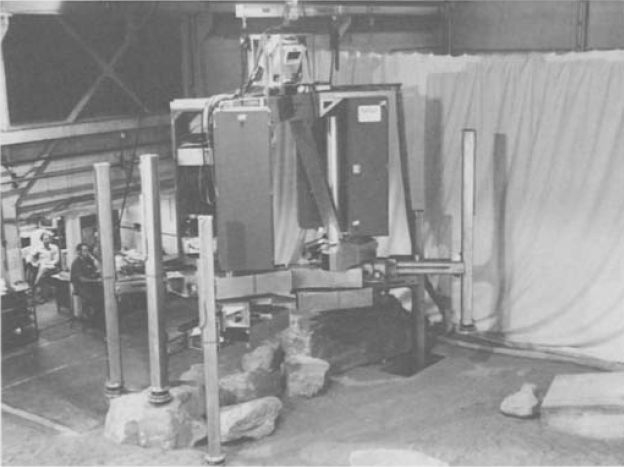

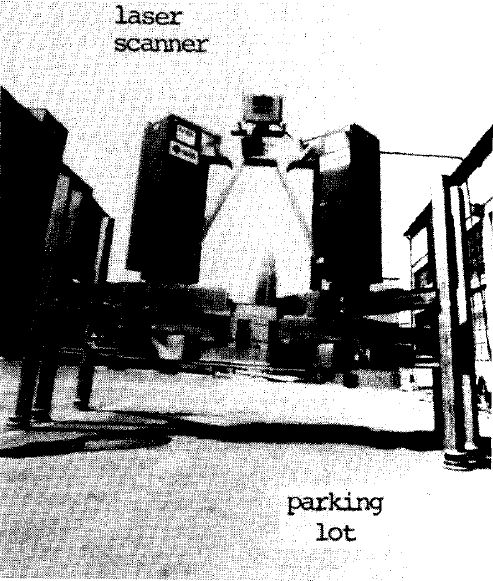

AMBLER showing time-lapse traces on one leg.

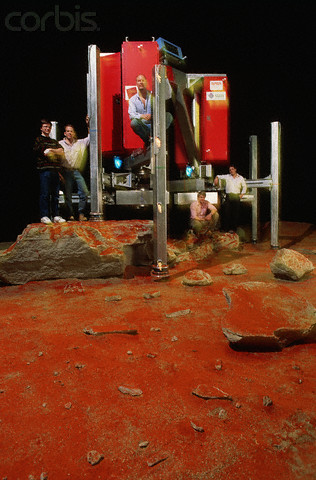

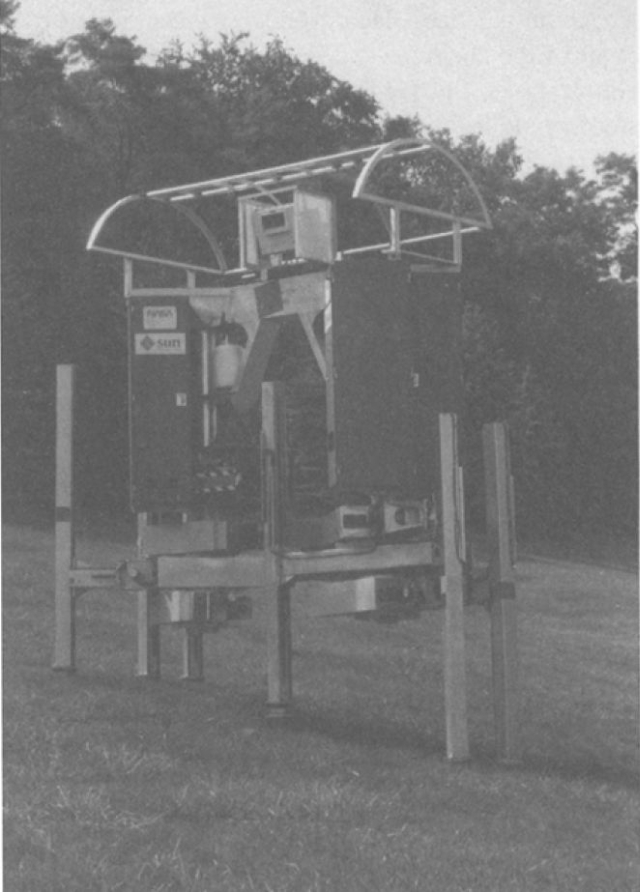

Some of the Carnegie-Mellon team with AMBLER highlight its immense size.

See a few pdf's describing AMBLER mainly here and here.

Below text sourced from here.

Ambler: Autonomous Orthogonal Legged Walking Robot

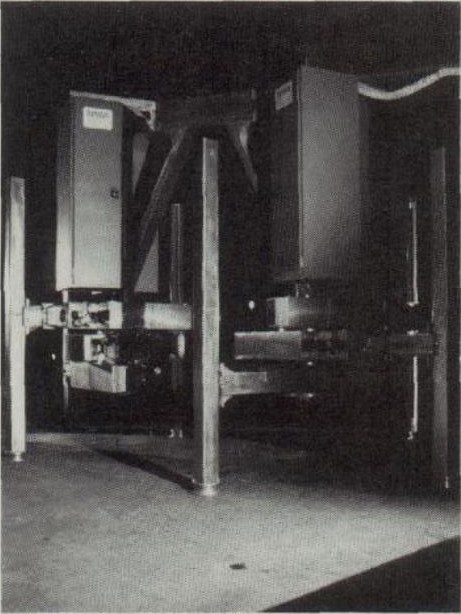

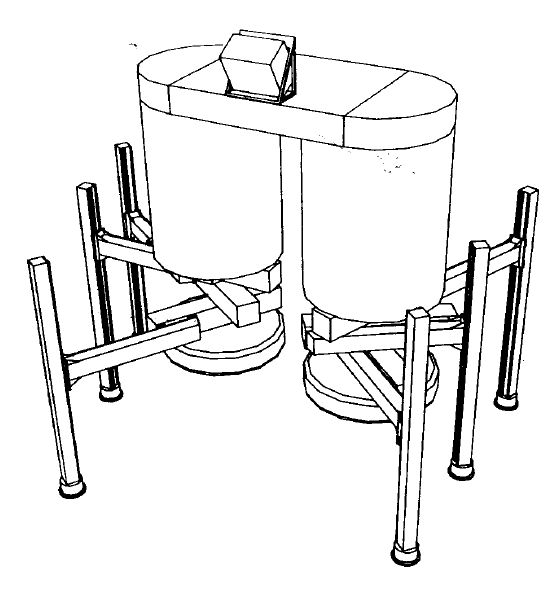

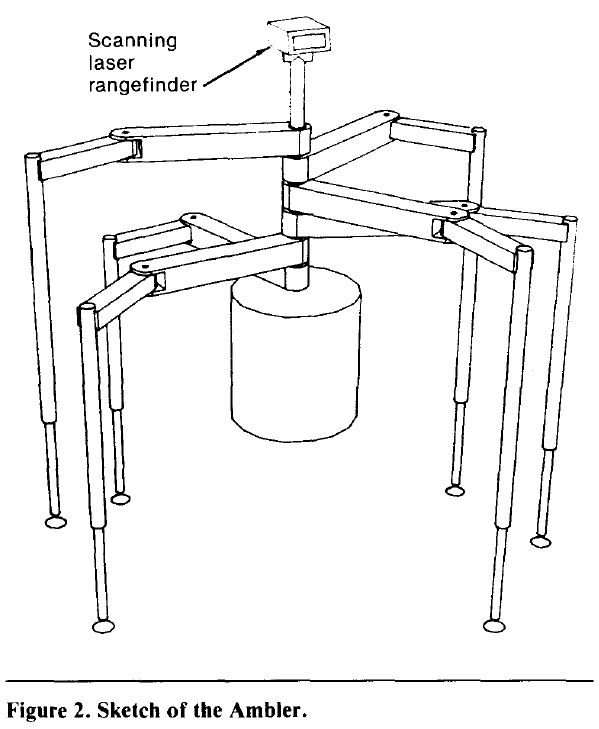

The Ambler robot was designed for walking under the particular constraints of planetary terrain, where there are meter-sized boulders, deep crevices, and steep slopes-an altogether inhospitable environment that defies humans and wheeled machines alike. Therefore, the six-legged Ambler travels over extremely rugged terrain without the close aid of humans. Autonomously, the Ambler builds detailed terrain maps; plans its own sequence and location of steps; and controls its movement, balance, and stability. In extensive tests, the Ambler has traveled thousands of meters, taken thousands of steps, and negotiated terrains that defy other robots.

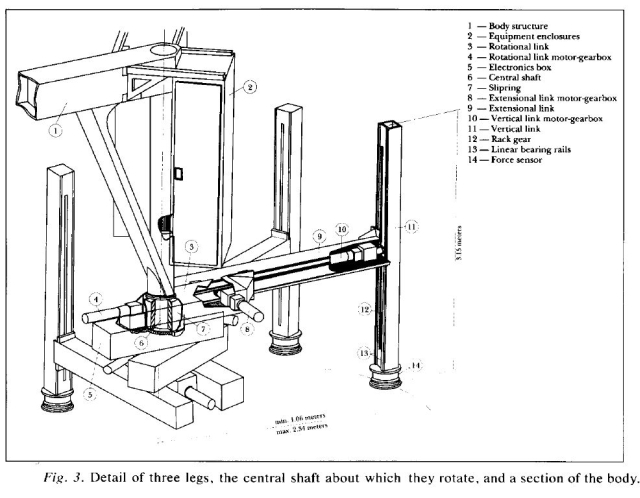

Walking

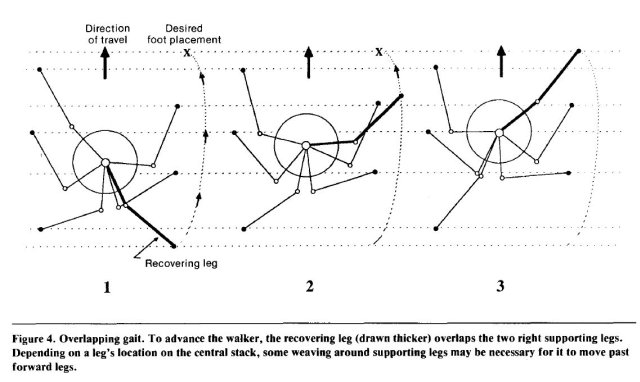

Ambler walks like no other machine and like no other creature in nature: Stepping with any leg in any sequence, the Ambler has the patented capability to move its rear-most leg past all other legs in order to travel over extreme terrain as efficiently as possible. Also, while most animals bend their legs to step and walk, Ambler's legs remain vertical, while they swing horizontally, then lengthen themselves vertically, like a telescope, to touch the ground. Such legs do not rock or sway in the act of stepping, thus risking unnecessary collision with obstacles. More flexible, animal-like legs require substantially more sensing and planning from a robot, but the Ambler's unbendable legs decrease both the consequences and the extra planning that would be necessary for bendable legs.

The robot's height of 3.5 meters enables it to step over obstacles as high as one meter. At the same time, no matter how rough the terrain, the Ambler walks upright, keeping its legs vertical and its body horizontalÑand keeping its laser rangefinder steady. It is through data from the laser rangefinder that the Ambler's perception system builds computerized maps of the terrain. (See Terrain Mapping, Krotkov.) In fact, Ambler's walking design facilitates perception of the terrain by maintaining a steady and level posture (on a 30 degree slope). When the robotÕs perception system merges laser images from different viewpoints into a larger composite picture of the terrain, the robot's stability gives its laser images a good registrationÑthat is, leaves very little unintended overlap and no gaps between the various image viewpoints. The robot's height also gives the laser rangefinder a high-vantage with which to better view the terrain, and promotes a high quality of sensor data.

Planning

Although remote human operators tell the Ambler where to go, the robot itself plans the steps it must take to get there (see also, Gait Configuration of Legged Robots, Wettergreen). The robot's gait planner takes into account not only terrain constraints but also its own walking capabilities: how far the robot's legs can reach, how long the legs can extend, how far the robot's body can stray from its center of gravity, where the robot can move each leg without colliding into another leg, and how it can place its legs so that its body-which moves alternately with the legs-also has a clear path to move forward.

After the gait planner has intersected all of these constraints and determined a limited number of steps, the footfall planner considers which of the available steps offer the best footholds and are more efficient in time and energy. The footfall planner has learned, through a neural network, which footholds are optimal, having been presented examples during its development of good and bad footholds. The leg recovery planner finally determines how to move each leg without colliding into something mid-move. At the same time, the robot's planners must weigh the various constraints. For example, the robot's body must move as far forward as possible (to increase efficiency of speed), without moving beyond its center of gravity.

Integration

Getting the various on-board systems to interact efficiently involves the use of Task Control architecture (see Task-Level Communication and Control, Simmons). Like a switch-board operator, TCA facilitates communication between the Ambler's various systems, coordinates the robot's plans, sequences tasks, and monitors actions and recovers from problems. Task Control Architecture enables planning, perception, and real-time control to work concurrently.

Early impression by the artist Erik Viktor.